Usman Riaz on Creating Pakistan’s First Hand-Drawn Animation Studio

Attending A4’s Town Hall on Film & Media this summer, I was introduced to the work of Watermelon Pictures, a Palestinian-led film production and distribution company based here in New York. Munir Atalla, the Head of Production and Acquisitions at Watermelon Pictures, presented a preview of their then-upcoming film, To A Land Unknown. The film follows two Palestinian cousins living in Greece as refugees. Without documentation, the two cannot work, dream, or be reunited with their families. The film is a lucid account of deprivation.

From then on, Watermelon Pictures had my attention; I knew I wanted to watch whatever they were putting out next. Their oeuvre is rooted in “creative resistance”, with features that include The Encampments, which documents the Gaza solidarity student protests led by Columbia University to Sudan, Remember Us which follows the 2019 revolution in Sudan. Most of their films are live action features—which is why I was surprised by their third summer release, The Glassworker, a Studio Ghibli-style animated love story by Pakistani musician and filmmaker, Usman Riaz. I wasn’t quite sure how this film would fit the rest of its slate. I only knew that I would be there in the audience watching it.

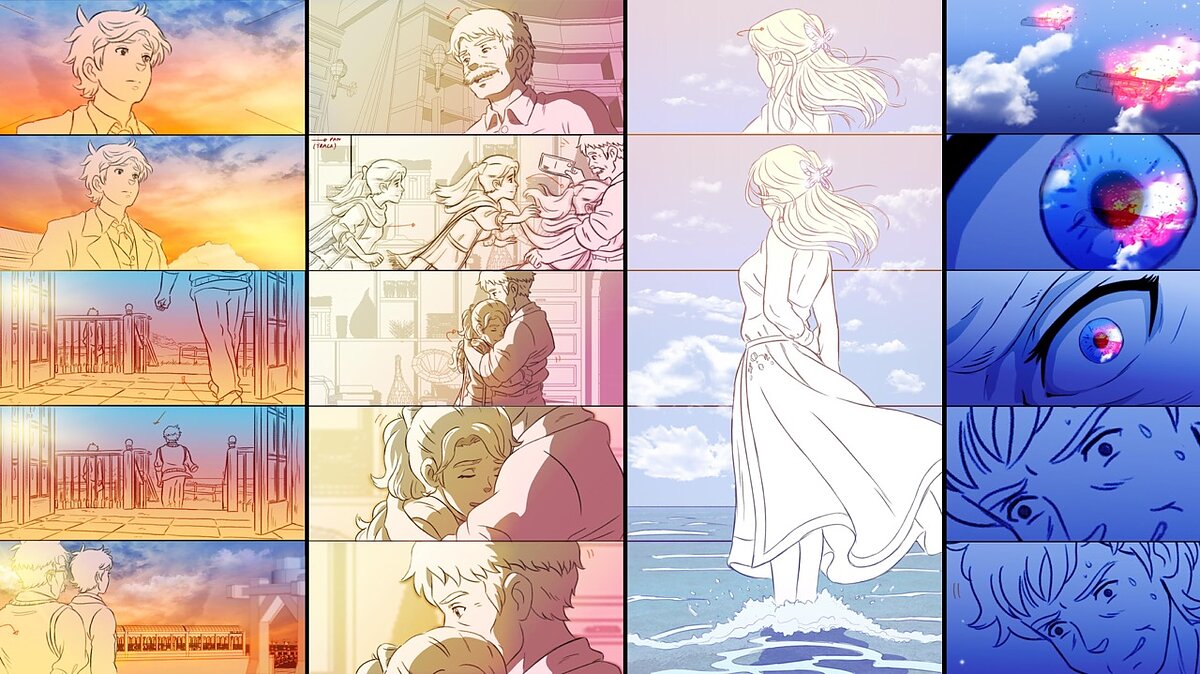

At an advanced screening in New York, The Glassworker opened with a supplementary documentary that revealed the film’s status as Pakistan’s first hand-drawn animated feature, and the ten years it took for Riaz and Mano Animation Studios to get the film made. While the production is, in and of itself, an enormous accomplishment, I found myself even more impressed by the film’s contents. Following the activist orientation of all of Watermelon Pictures’s films, The Glassworker is not only visually beautiful—it illustrates the personal effects of war and how it intrudes on the lives of ordinary people. Set in a small fictional coastal town, the film follows pacifist glassworkers Vincent and his father, Tomas as their craft is co-opted into fueling war. Tensions deepen when Vincent’s only friendship with Alliz, the daughter of the town’s commanding general, blossoms into a forbidden romance. The film is as much about resistance as it is about coming of age.

The Glassworker is currently playing in theaters across North America. Ahead of the film’s nationwide release on September 5th, I caught up with director Riaz (who is also a classical music prodigy once featured on NPR’s Tiny Desk and former TED fellow) to discuss identity, inspiration, and delusion as a filmmaking strategy.

UR: I identify as Pakistani. I’ve spent a lot of time in New York because my mother’s family is here. So every summer and winter, we would be here.

The other reason I would come here and to England is because I’m a type 1 diabetic. In the late ‘90s, Pakistan didn’t really have diabetes specialists the way we do now. I would get my treatment here, standard stuff, checking my blood sugars, and having doctors monitor everything. But coming here has been a big part of my life–I was here during Hurricane Sandy.

My wife is Pakistani American. She was born here and lived here till she was 12, then went back to Pakistan. Now, we’re back here.

I would like to identify as a New Yorker. I think that Pakistan and New York are very, very similar. Everyone is always angry and in a rush to get somewhere. There are a lot of similarities. I think I fit in quite nicely here.

UR: The film is done, thankfully. There is not as much to manage as there was. When I first started the Kickstarter ten years ago, I was at Berklee College of Music, coming to New York to prepare everything. I would spend my days in classes at Berklee. Then, at night, I would stay up and manage the film. That was one of the more difficult years of making the film, because I would be so exhausted by the end of the day, but then I would have to work Pakistan hours.

I would be on Skype calls from 1 a.m. till about 6 or 7 a.m., try to sleep as much as possible, then go to my classes the next day. That’s why I dropped out.

The film was building up so much momentum that if I didn’t pick one thing to do, I don’t think it would have transpired the way it did. It was a scary decision. But ultimately, now, 11 years later, I can say it was the right decision for me.

UR: Making animation and movies was always the dream. But growing up in Pakistan, the film infrastructure wasn’t and still isn’t great. There’s very little government financing for anything, or tax rebates on anything you do. We’re not motivated to make art in the country. I never thought it would be a possibility while I was growing up.

In summer 2015, I went to TEDx Tokyo–I spoke there. I poured my heart out about how much I love Japanese animation. I talked about Studio Ghibli and all my influences. Miraculously, I was invited to Studio Ghibli. That was amazing. I sat in the cafeteria with Shin Hashida after I saw Miyazaki working, which was another mind-boggling experience. After seeing all my drawings and my storyboards, [Shin Hashida] told me that if I worked in Japan, it might take me six, seven, maybe ten years till I’d be in a position within the industry to direct a feature. There’s no guarantee that I’d get to direct it as soon as you enter the industry. He told me I was clearly talented and knew what I was doing—and that I should start my own studio.

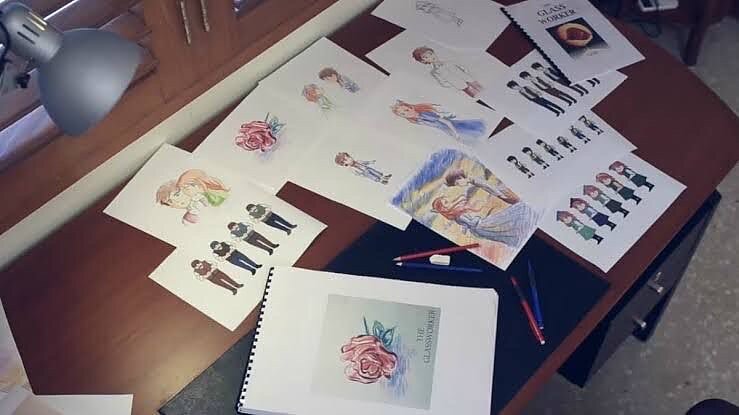

I went back to Boston, and Mariam [Paracha] and I co-founded Mano Animation Studios. Our Kickstarter raised about $116,000 to make a pilot animation. Once the Kickstarter was done, we started to expand the team, and I was staying up way longer. I decided around the end of 2016 that I’m going to slow down. Initially, I didn’t think I would drop out of Berklee. I just thought, okay, I’ll take fewer classes. I’ll spread it out more. That wasn’t working.

Ultimately, we had to take a call that we should go back to Pakistan and finish this movie. I didn’t think it would take another seven years. It was very scary because I had a full scholarship, and many students wanted to be in my position. It felt extremely ungrateful. My hands were shaking when I wrote to the dean that I’m going to drop out and go make this film. He actually said, “No, no. Let’s talk about it.” I said, “No, I can’t talk about it or it will make me doubt my decision.”

UR: I was selected to be a TEDx fellow in 2012, so since I was 20 years old, I was in an environment where I saw pioneers and amazing individuals pursuing what they believed in, even when the world was saying it’s impossible. They’re not gigantic, super famous people; they’re just brilliant people who believe in the vision that they have and are pursuing it 1,000%.

Being around that environment was very infectious. I knew it wasn’t impossible. It’s just a matter of getting the right people together and working extremely hard.

What actually got me through it was sheer and utter delusion. There’s no other way to put it, because to a lot of people, I did sound delusional. And seven, eight years into the journey, I also felt like I was being delusional. Thankfully, we were able to pull it off.

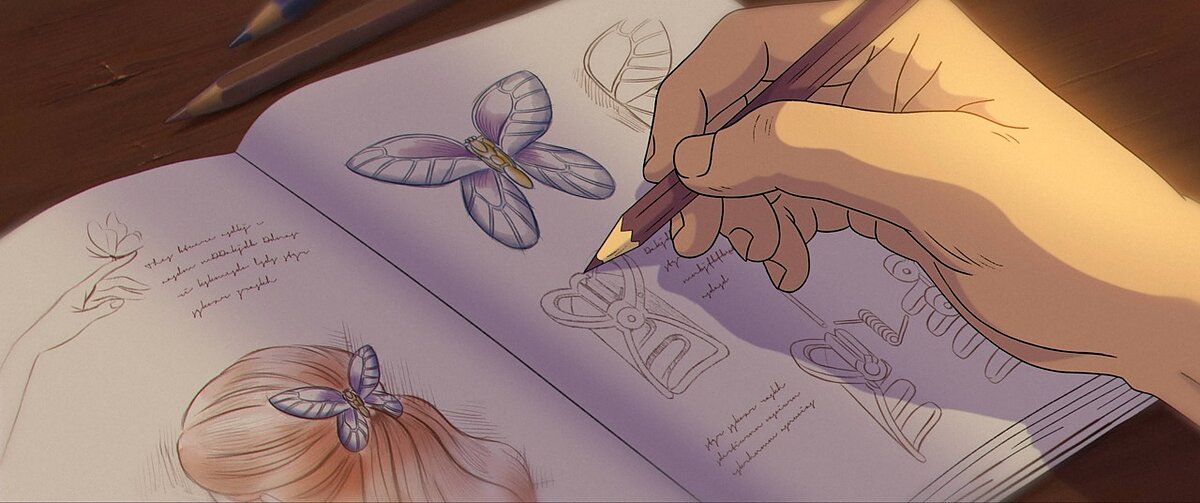

UR: I first came across glassblowing when I was 14 years old. I saw the Murano glassblowers in Italy, and I was fascinated by the process. The way glass is made is just as beautiful as the end result. I didn’t think I would make a movie about it—it was just something that I was very, very interested in from when I was 14 until I was about 23.

I watched a lot of documentaries. Whenever something about glassblowing would be on, I would watch that. I had a few books about it as well. It was a fascination that I had, again, not thinking that it would be so useful.

When I decided to make 2D hand-drawn animated films, that was the first medium that I thought would be interesting to showcase. Something we haven’t seen before. I was hoping and praying that by the time we finished the movie, no one would have done it yet.

The way you can control the colors and the unpredictable nature of glass, in animation, you don’t have to deal with that. From a practical point of view, doing it in animation versus live action was also easier.

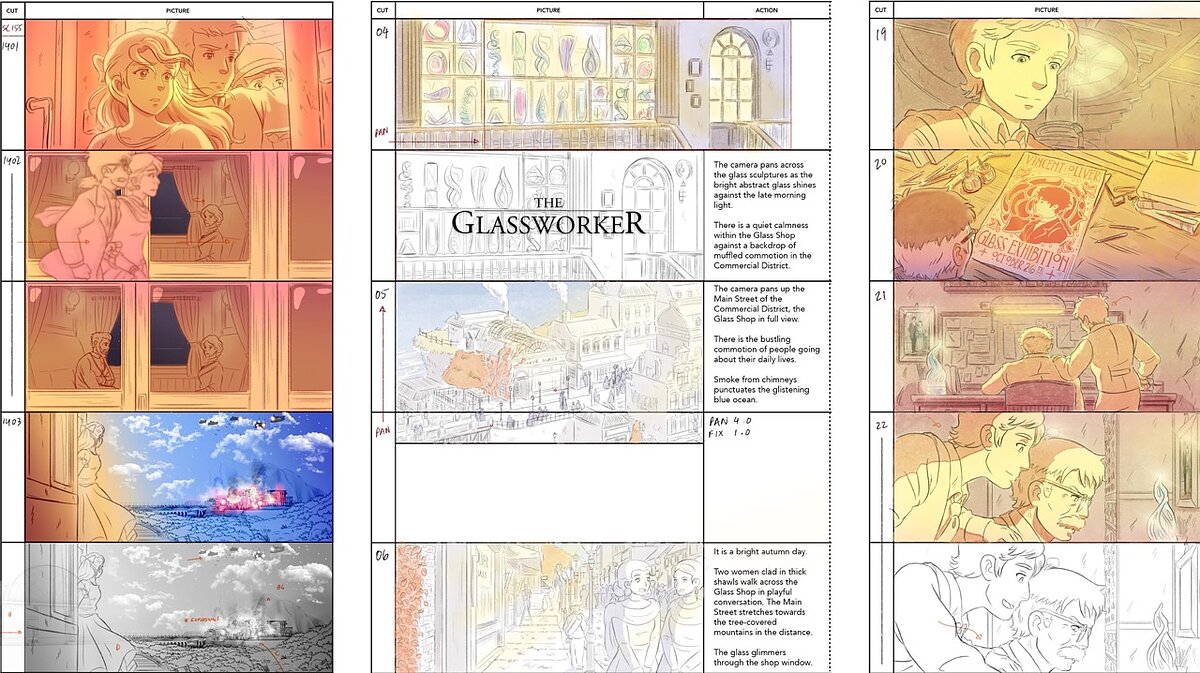

UR: I didn’t start with the script. I started with image boards. I started drawing this father and son in their workshop, making glass, with the idea that a war is surrounding them. But it’s just these two characters in their own little world making their art form.

I didn’t draw digitally at the time. I would wait for my watercolors to dry, then I would write music for those visuals that I had drawn. That’s where the musical motif for the film quickly started forming—The Glassworkers Melancholy in D minor. I kept drawing image boards and writing music. All of this came together very, very quickly.

I started storyboarding the film and once I had all of my image boards ready, I began showing them to people and slowly started to build a team. I made three different versions of the storyboards. There were the traditionally watercolor-drawn ones. Then, there was the version of the story that we ended up not using. I made about 300 shots for that, and then the version that we have now.

UR: When we started making the film, we worked with Geoffrey Wexler, the Chief of International for Studio Ponoc and Studio Ghibli. He brought on board Moya O'Shea, who helped with the script. While we were in London, after finalizing the script in 2018, we were invited to the famous glassblower, Peter Layton’s, studio. I shot five or six hours of footage there and interviewed the glassblowers about everything. Then I edited together a 20-minute documentary, for internal use, so that whenever somebody would come on board, they would get a 20-minute crash course in everything related to glassblowing. That was fun. Then our animation team, especially our animation director and art director, worked together to create a look that, when the glass moves, the light and colors looked beautiful, but also were accurate to the caustics of glass.

The characters and the story came from a very personal place. The world changed after 9/11; I was eight at the time. Thankfully, Pakistan didn’t see any real conflict, but you would always hear about it in bordering countries. There was always this underlying sense of anxiety and tension that the world could fall apart tomorrow.

When you’re eight years old, you don’t really understand what that means. But you certainly have the instinctual understanding that something is very wrong. Especially for a sensitive, creative artist. You tend to wonder what your place is in the world and whether your contributions are actually felt, that people actually appreciate them—what are you doing when the world around you is falling apart?

That’s where the story started coming, the glassblowers are trapped in these larger-than-life circumstances around them, where the world is falling apart. But all they have is their craft to focus on and get through the day-to-day and keep moving forward. Alliz’s character, the violinist, came from my classical music background. The way both characters interact is very much like conversations that I would just have with myself growing up, where I didn’t understand how art could really help in making the world a better place.

UR: I grew up playing classical piano. The world of classical music is very repertoire-heavy, and it’s not your own music. The way you interpret the pieces is your stamp on it. I wanted to write my own music, and that was something I would talk to my teacher about.

He was a wonderful man. When I was a child, I had a choice between the violin and the piano. My teacher told me that if I want to write music, then I should learn the piano. But what if I had picked the violin instead? That’s why Alliz plays the violin and not other instruments.

When I was about 14-15, that’s when I started writing my own music. I finally felt like I had a voice because up until then, all I was doing was learning Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt. I loved playing those pieces, but there’s so much more fun in writing your own. Alliz in the story kind of echoes what I did back then. It was fun exploring different sides to my artistic journey through these two characters.

UR: That was a very intentional choice. Never for a moment did I want the film to feel preachy with its worldview. Also, by grounding the film in Pakistan, I would have made it a geopolitical statement of this war happening with another country. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted it to be open to interpretation.

I wanted people to feel for these characters, but that doesn’t mean the setting that they’re in should not be influenced by Pakistan, where I grew up. All the sights and sounds were very, very specific in the art direction with Mariam and me. In terms of the architecture, there’s a lot of influence from the Islamic Eastern architecture that you see peppered throughout Pakistan, but also the colonial architecture that is very much a part of our history as well.

A lot of the buildings you see, kids, bazaars, stalls of different fabrics and clothes and food, street vendors, are all the things that you would see in a typical market in Karachi. Specifically, the marketplace that we’ve depicted is Empress Market. We want to have specificity in these locations to give the film a different visual identity. I was intentional about taking something animation audiences are familiar with and injecting it with our culture.

UR: If it has, I haven’t been informed about it. But, most probably. I set out to make something where people could see the humanity of these characters. I never imagined that by trying so hard to stay away from any real-world events ten years ago, it would still be so relevant when we were releasing it. I’m not happy about that.

I wrote the story in 2013. It was my point of view on events that were happening at the time, so it’s interesting to see how this is still relevant now. It brings me great sadness. But if the film can allow people to see the humanity of the people who are caught in conflict, then that is the victory.

UR: I’m so grateful. Every step, every milestone for this film has led to something that has led to something else. It’s taken a lot of time. But when I look back on the whole journey, I see all the puzzle pieces fitting together.

We were Pakistan’s submission to this year’s Oscars. We weren’t nominated, but we were on a long list for International Feature and short list for Animation—a huge honor, because I never thought we would be in this position. Through that, I was able to work with the Gotham Group and because of the publicity, Watermelon Pictures saw the film and believed in it so much.

There were a few conversations we were having with other people who wanted to make significant changes to the movie, which I really didn’t want to do. I’m very, very grateful that we found the perfect distributor for this film, who believes in the movie the way it is and understands its messaging.

UR: People are certainly more inspired. They’re creating their own studios and they’re making shorter, independent animation content. That makes me happy. If our film contributed to their journey in a small way, I’m very grateful for that.

At the end of the day, it’s also funding that makes and allows projects like this to exist. I’m cautiously optimistic about the future of the animation industry within Pakistan and within South Asia. But we’ll see if people are actually willing to fund projects like this, because I worked very, very hard to get the money to be able to make this film.

The budget wasn’t huge by any means—I would say it was a fifth of the budget of Japanese productions, but it was still a substantial chunk of money for a Pakistani film. That is one of the miracles of this project, too, that we were able to actually secure that funding and make this movie, for which I will be grateful for.

I hope we can lead by example, show that stuff like this is possible, and inspire not only the talent, but also the financiers of the talent to believe in projects like this and help make them a reality.

UR: My family and family friends financed this project. Out of respect, we call them investors, because we treat them professionally. My mother sold my grandfather’s house to be able to fund a part of this project. My father funded most of the Pakistan side of the production. Our main investor in California is a close family friend.

It was really these three people that believed in this project and allowed me to make it. I don’t talk about this often, but I’m very grateful to my parents and our friends who were able to support this because without them, this wouldn’t exist.

UR: Only Ghibli can make Ghibli. There have been people who have tried copying the style in video games and other things, it just never looks that way because of the cognitive dissonance that this isn’t Studio Ghibli.

I wanted to evoke it, but also do our own thing. The biggest inspiration outside of Ghibli for this film is actually Disney’s Pinocchio. You can see a lot of visual callbacks. Gepetto’s workshop is the glass workshop, Thomas and Vincent are Gepetto and Pinocchio. It is also the emotional arc of the story. It starts off with youthful exuberance, with Pinocchio discovering the world, the way Vincent is coming into adolescence, where things are taking a darker turn.