Returning Home: Growing up as a Chinese Bolivian Immigrant

I’m from Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia. Both of my parents are Chinese and immigrated there from China in 1980 to flee communism under the Deng Xiaoping regime. They still live in Bolivia today.

In 1998, my parents separated. The following year, my grandmother brought my brother and I to the United States where we lived in Jamaica, Queens, and briefly attended P.S. 131. After our 30-day travel visa expired, we became undocumented. We moved to Doylestown, Pennsylvania, where we stayed with our uncles who weren’t technically related to us, but became our legal guardians.

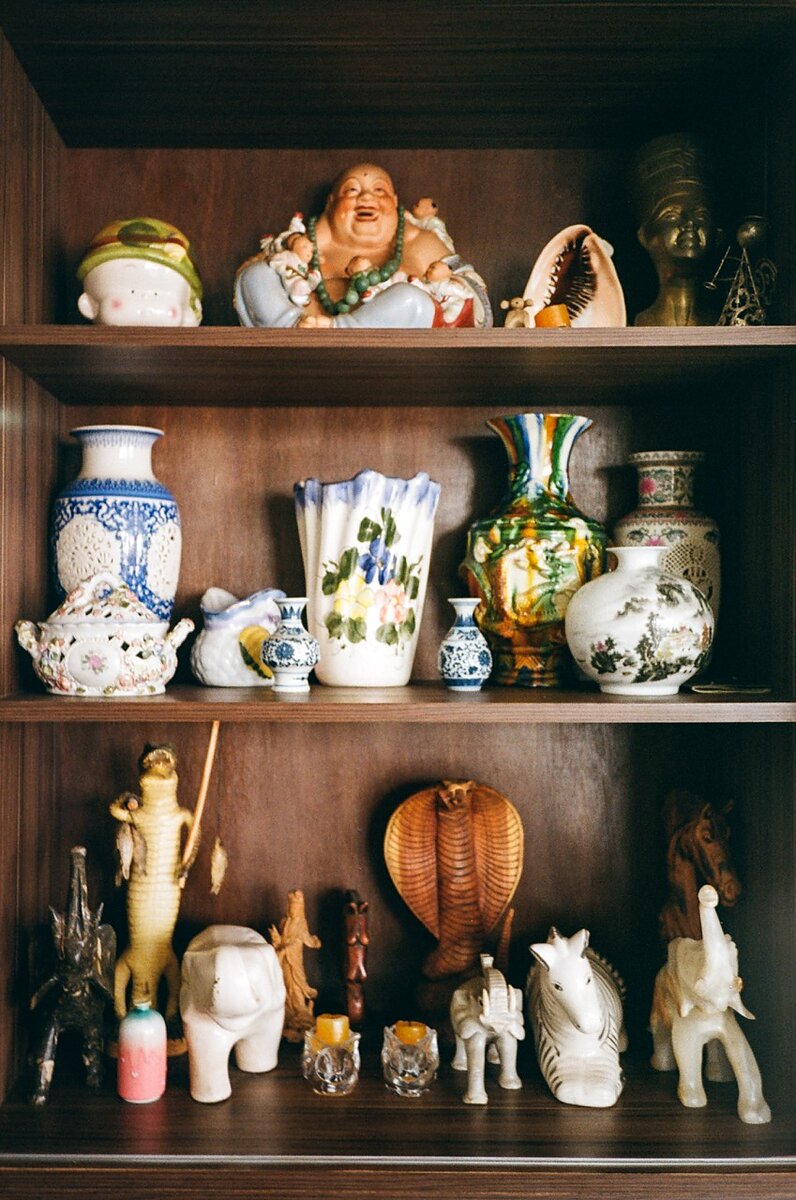

Back in Bolivia, my uncles worked for my dad’s restaurant, Chifa China. The word “chifa” means “to eat” in Mandarin. It also refers to a culinary style that fuses Chinese and Latin flavors. In Doylestown, my uncles opened their own Japanese fine-dining restaurant, originally named Tokyo D. Sushi, where the servers wore kimonos. Later, they rebranded as Ooka Japanese Sushi and Hibachi Steakhouse.

My brother and I spent a lot of time there growing up, hosting and bussing tables. I bought my first MacBook Pro with the money I earned. In high school, I discovered Flickr and began contributing my photographs to the online community after I bought my first DSLR camera, a trusty Nikon D50. My uncle and I split the cost 50/50 so I could afford it.

I would walk around taking photos of my friends, collaborating on mini “test shoots,” and photographing abandoned barns and buildings around my neighborhood. Being creative gave me a way to escape reality, even if just for a moment. The act of creating something out of nothing still brings me great joy and fulfillment.

I remained undocumented until 2012, when the Obama administration passed the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. DACA granted protection to children who had been brought into the US at least five years prior to June 15, 2012, and were still without legal status. It also provided eligibility for work authorization and deferred action from deportation.

I remember my uncle calling me while I was in college in New York City, urging me to apply for DACA. My application was accepted in 2013. For the first time, I was allowed to legally work in the US, I never had a valid Social Security number until then.

Being a “Dreamer” (as DACA-recipients are called) allowed me to grow, granting me legal protection toward naturalization—it also had its limits. Because of the program’s strict travel restrictions, I was exiled in the US for 23 years before I could finally return home to Bolivia and see my family.

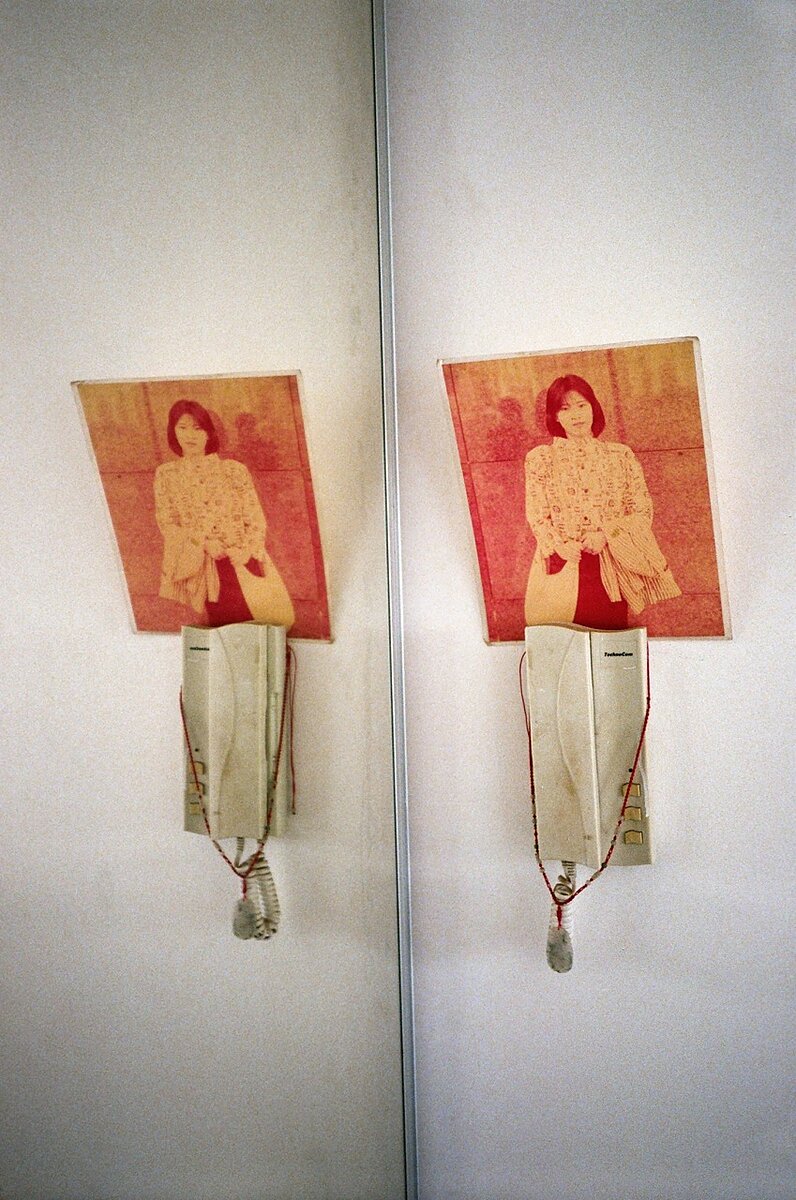

In 2021, I received my green card after my wife and I got married, which allowed us to travel internationally. We went to Bolivia the next year. That trip was incredibly important to me, not only because I got to reconnect with my family after over two decades, but also because I got to introduce my wife, Yuliya, to them—my mom, my dad, my brother and his kids, my sister-in-law, and my stepmom.

The trip also allowed me to photograph the people and places that shape my hometown. Bolivia has a small but thriving Chinese diaspora; according to a 2016 census, of the country’s 10.8 million people, Chinese Bolivians make up about 7,000. Most of them live in Santa Cruz, where my family lives. The Chinese consulate there is bigger than the one in the US.

We visited Concepción, where my brother Nick and his wife Angela work. My brother took over my mom’s company in 2018. They sell and distribute lumber globally under a distribution license.

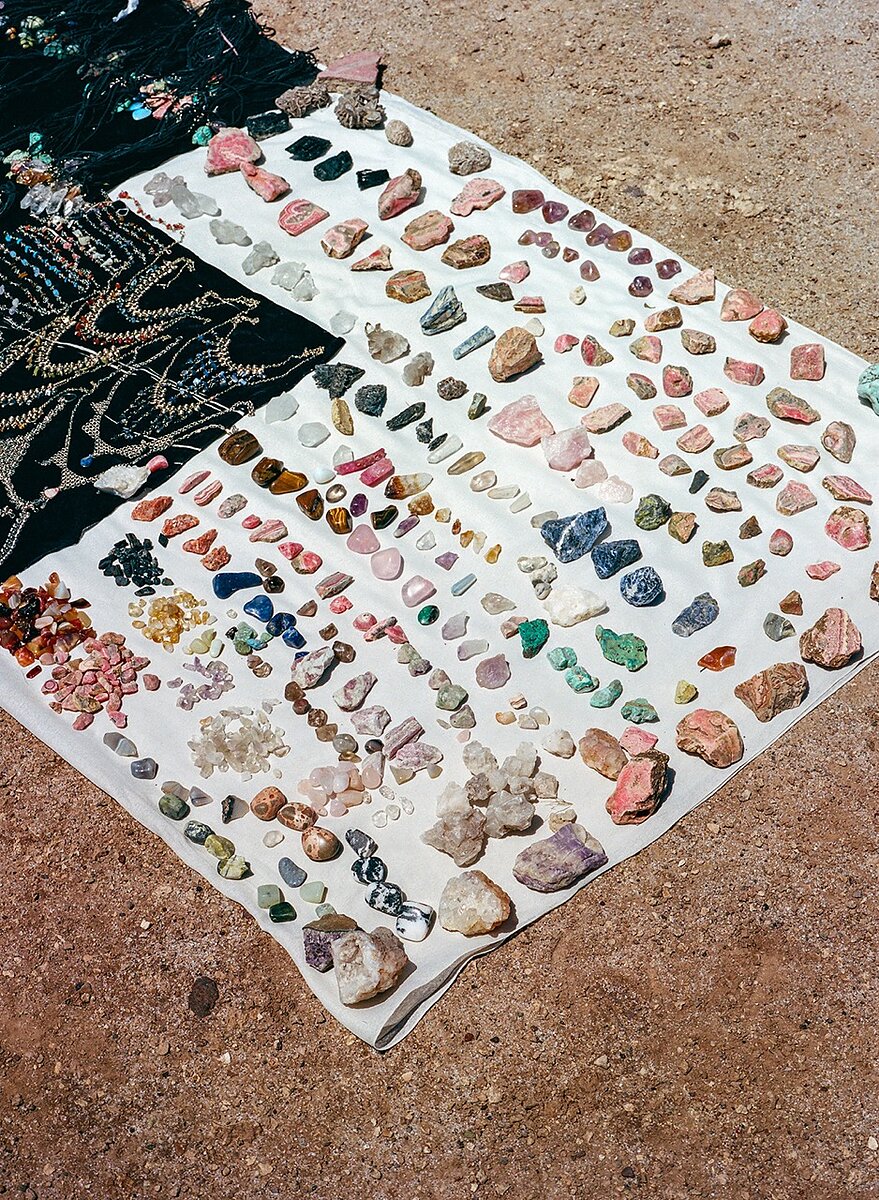

Wandering around the city’s markets, I photographed the rich Indigenous cultures on display representing the Aymara, Quechua, Chiquitano, Guaraní, and Moxeño communities. We ate salteñas, Bolivia’s famous baked empanadas with a savory soup filling, and mocochinchi, a refreshing, caffeine-free tea made from dried peaches, cinnamon, and clove. Throughout the vibrant colors and artistry, stray dogs roamed the streets and panhandlers were everywhere.

We took a trip to Salar de Uyuni, the Bolivian salt flats. The views were breathtaking, though the high altitude made us feel lightheaded and nauseous. We spent the day under the sun taking cheesy tourist photos—our guide helped us stage perspective tricks, like Angela stepping on Nick and Yuliya stepping on me. It almost looked Photoshopped.

Returning home to Bolivia after so long felt like revisiting a dream. As an adult, you realize how much smaller everything is compared to your childhood memories. Places like Siete Calle once felt enormous, a reflection of how young I was when I first encountered those spaces. My brother’s kids are growing up, and it’s been nice getting to know their personalities.

For me, being able to return home is more than nostalgia, it’s a reminder of the long journey that took me away from this place, and the privilege of being able to come back. Not everyone in my situation has that chance, especially now, as immigration crackdowns in the US make the idea of leaving and returning even more uncertain. To embrace the truth of where we come from is what allows us to move forward without losing ourselves.

—James Huang is a Bolivian-born Chinese photographer currently living and working in New York City. He received his BFA in Photography and Imaging from New York University - Tisch School of the Arts in 2014.