Suniko Bazargarid on Reflecting the Bureaucreacies of Migration

I first met Suniko Bazargarid recently outside the International Center of Photography’s Photobook Fest, a book fair that brings together image makers from around the world in an unassuming building at the heart of downtown Manhattan. It was Saturday evening, and many people leaving the event lingered in front of the entrance, enjoying the warm early fall air. Bazargarid, chatting and laughing among a vibrant group, recognized my photographer friend that I was leaving with.

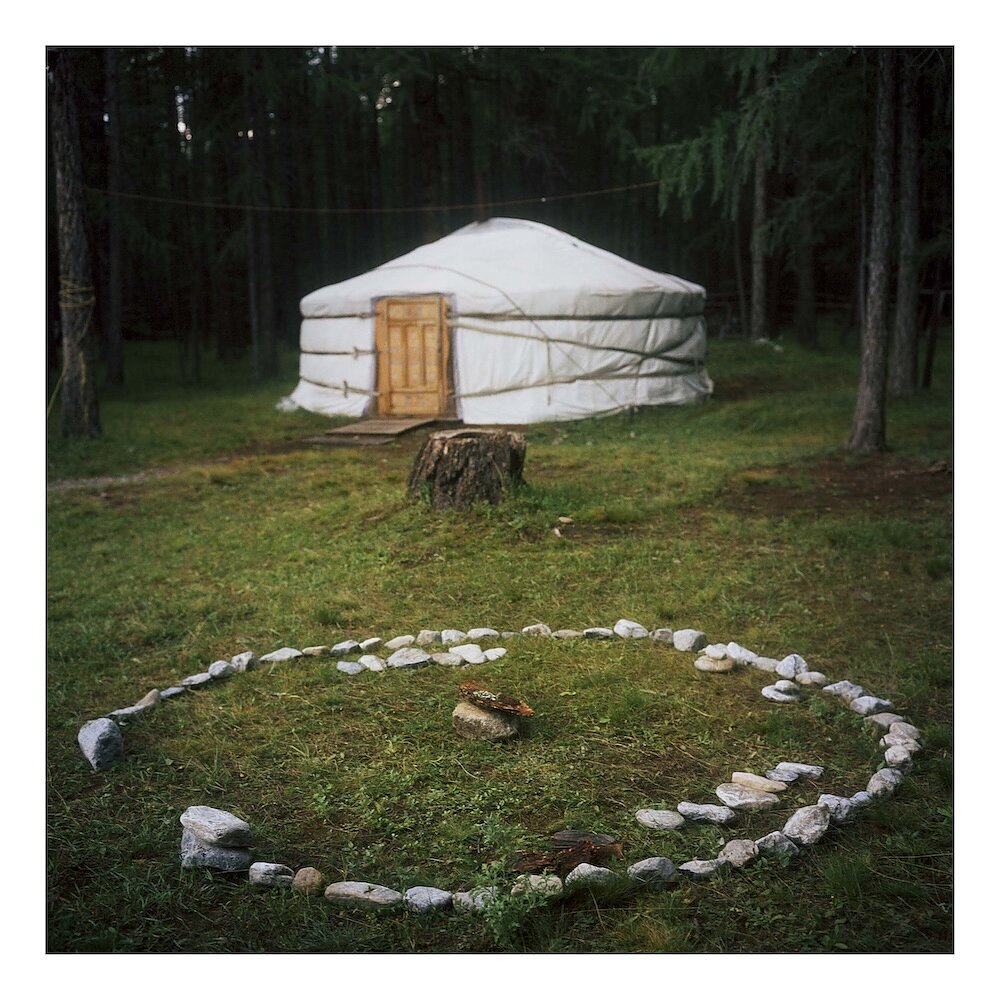

After a brief introduction and exchange of information, I realized she was the artist behind the current exhibition at Baxter Street Camera Club of New York. Titled “Where would we find you if we need to find you?,” the solo show (on through November 12) features works by Bazargarid that reflects on her experiences growing up between Boston, Singapore, Bangkok, and Mongolia. They offer a quiet yet poignant contemplation on how a nomadic individual collects, rearranges, and reflects on her interlaced and multilayered memories, identity, and migration history. Moreover, the work exposes the tensions and power imbalances between bureaucratic systems and individual agency. As the gallery notes in its introduction, the exhibition’s title functions “both as a practice inquiry and as a charged reminder of regulation, visibility, and control.”

In the constellation of photographs created by Bazargarid, symbols of portals and restraints—doors, window frames, and fences—are juxtaposed with natural landscapes, cityscape, and objects rich in cultural and ritual resonance. Together, they remind the viewer of the contexts and perspectives through which her work can be examined and contemplated. These elements are multilayered and intertwined to the point of merging into one another, making it impossible to distinguish a single kind.

I continued my conversation with Bazargarid on a chilly Tuesday morning at Baxter Camera Club, where we discussed her work in greater depth. Embodying the transitory themes of her work, Bazargarid mentioned that her stay in New York might only be temporary as she had been struggling to secure a longer US visa, with no clear sense of whether it would be extended or end at a certain point, or where her next destination might be.

SB: From the beginning, I envisioned this exhibition as a physically engaging one. I wanted people to be able to walk around and interact with it. While I do love the individual images and each has its own meaning, once all the works were curated and hung in the space, it felt more like a single, cohesive piece.

All the big pieces—the sunsets, the moonrise, and the landscapes—were the ones I knew would be in the show from the very beginning. The largest one on the floor was the first piece for which I decided on the size and placement. I initially wanted the endpoint of the diagonal line in the photo to start from the entrance, so it could provide a visual guide for visitors as they moved through the exhibition. But in the end, we couldn’t do it that way due to the limitations of the space.

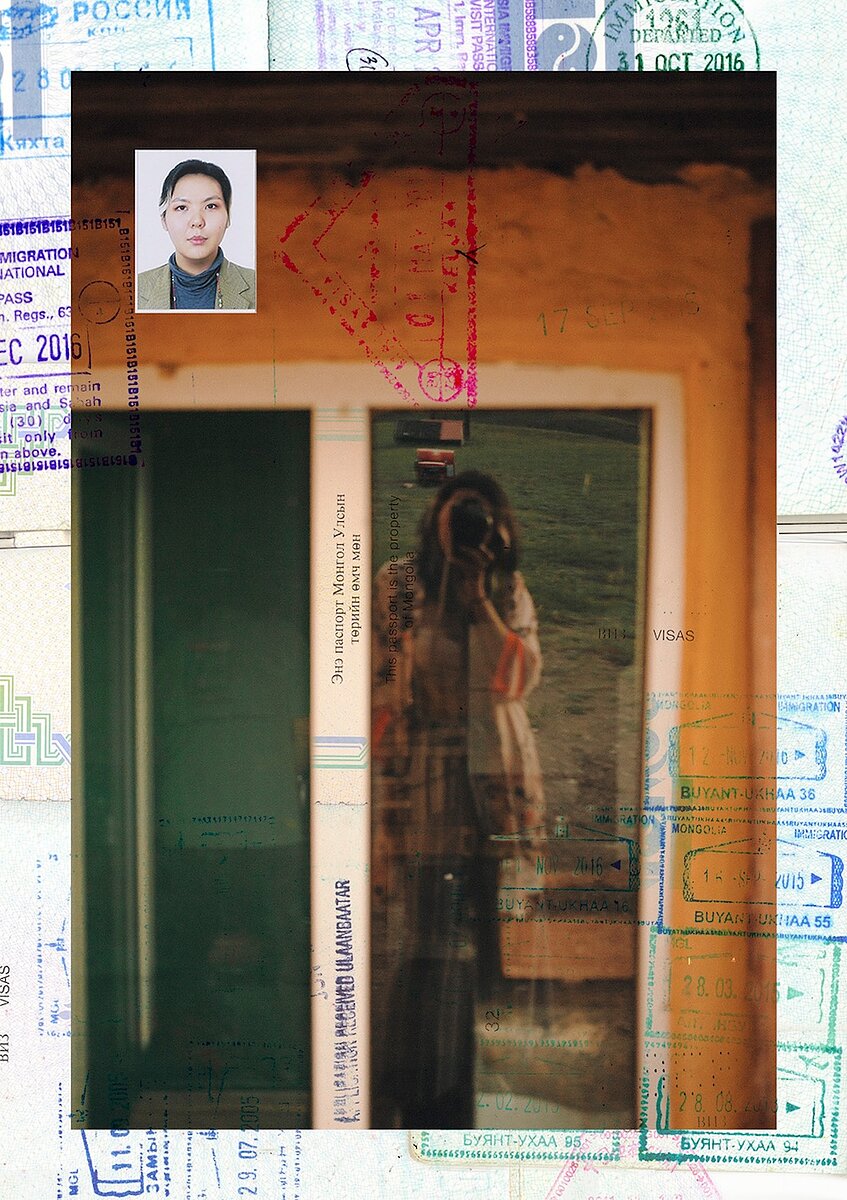

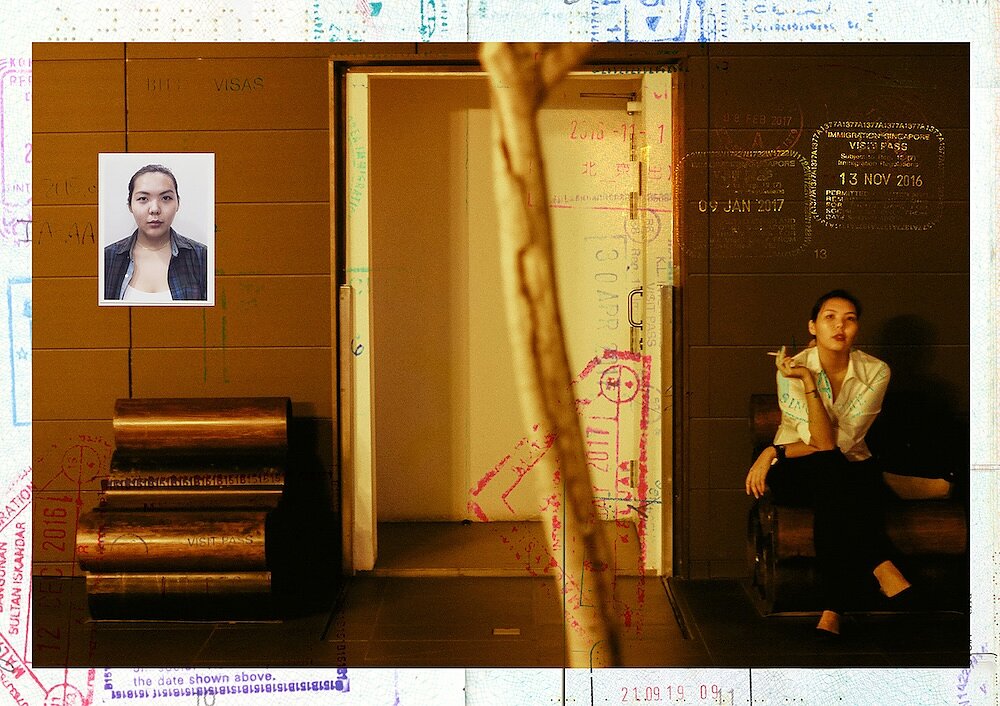

SB: I couldn’t frame them all because of financial restrictions. I decided to frame the selfies because they’re postcard-sized, and I wanted them to feel like objects. Also, since they’re digital collages, they would feel a bit flat if I just left them on their own.

These photos of myself exist in the exhibition the way punctuation exists in a story or a poem. I am the one who has experienced all these immigration stamps and the many places where these images were taken, and at the same time, an observer of the entire narrative, seeing all these things alongside other viewers.

I took them over the course of several years. The first one, near the entrance, was taken when I was 16 in Mongolia, and the others were taken at ages 19, 20, 21, and 23, in Singapore, Bangkok, and Mongolia—places where I used to live.

SB: I wanted to see what the stamps would look like on the land. Recently, Mongolia upgraded its passport design, and now every page has these beautiful landscape illustrations—it looks really nice. And I was thinking: we put stamps on the landscapes in the passport, so what if we put the passport on the landscape? Like a reversal. The stamps also symbolize the time and paths I’ve taken.

For one photo, I aligned the borders of the passport page with the borders of the image, as if expanding the landscape. In another, I placed the pattern of sun rays from the passport into the sky, just playing with the textures. I also placed some bureaucratic terms from the customs stamps onto the photos, for example “Change of purpose not allowed. No work for business,” punctuating the images with the bureaucratic restrictions and orders one might encounter while transiting from one place to another.

“Where would we find you if we need to find you?” is on at Baxter Street Camera Club of New York through November 12, 2025.

—Jenny Jiani Wang is a bilingual writer and visual artist whose practice drifts between fiction, non-fiction, and video installations. She is drawn to the sensual and emotional undercurrents beneath material and systemic surfaces, seeking to understand how private moments resonate within broader histories and collective structures. She holds an MSc in City Design and Social Science from the London School of Economics and an MFA in Photography, Video, and Related Media from the School of Visual Arts in New York.