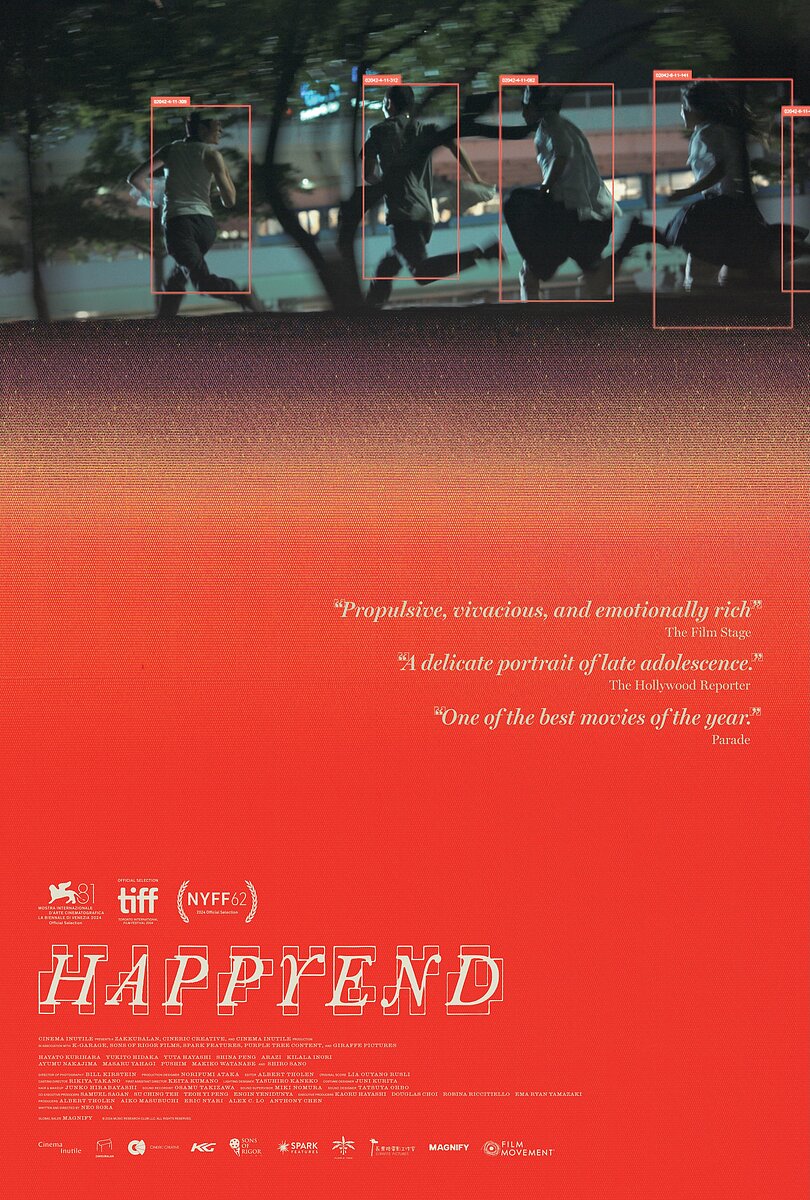

Filmmaker Neo Sora on Surveillance Aesthetics, Japan, and Palestine

The kids are decidedly not alright in director Neo Sora’s dystopian coming-of-age film, Happyend.

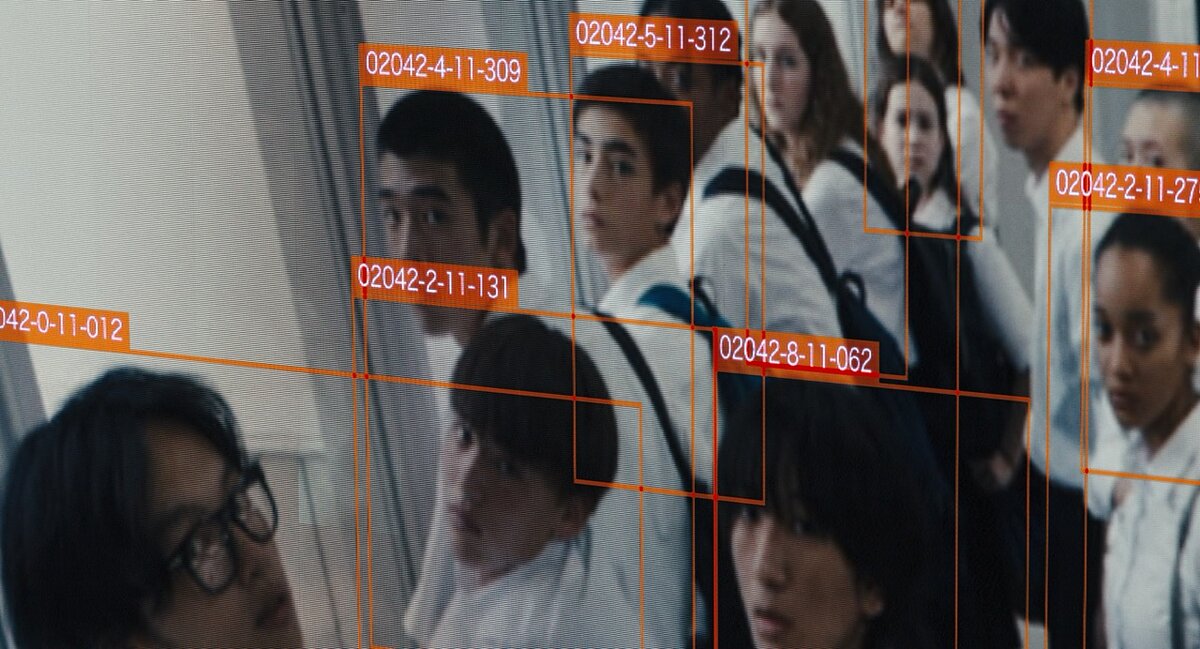

Set in a near-future Tokyo, the film follows two best friends, Yuta (Hayato Kurihara) and Kou (Yukito Hidaka), who dream of making techno music together. When the two pull a prank on their principal, the administration sees it as an opportunity to introduce a new surveillance system at their high school. Cameras are installed in every hallway and classroom, and whenever someone steps into the camera, the system’s algorithm makes pre-judgements about their behavior, giving the schoolgrounds to punish more liberally. What’s happening in Yuta and Kou’s school is a distillation of what’s going on outside of the classroom walls: the film’s Prime Minister is using the looming threat of an earthquake to expand the reach of his military’s power and influence. Inspired, Kou takes up activism, straining his relationship with Yuta, who would prefer to keep the peace.

Sora’s film masterfully finds ways to tell not only a touching and heartbreaking story about a friendship that frays due to political differences, but also comment on the way fascist regimes exploit the legitimate fears of their populace to exert more control.

Regardless of how you choose to read Happyend, Sora insists that you view all of its seemingly discordant notes as part of the same symphony. “Audiences in the west typically don’t see that the disparate elements of the film are actually the same,” he told me, “A lot of people separate the characters from the authoritarian, surveillance, and foreign backdrop… in reality, it’s all fundamentally about colonialism.” Ahead of the film’s US theatrical release, Sora spoke with me about the dovetail between his own political awakening and creative growth, how his filmmaking intersects with his work in Palestine, and the sinister aesthetic of his on-screen surveillance system.

Minor spoilers for Happyend follow.

Neo Sora: My political convictions probably would not be where they are right now without my interest in the kinds of films that I watched both as a kid, but also when I was at university. I would watch a lot of Japanese cinema from the sixties and seventies from directors like Nagisa Ōshima and Shūji Terayama. Their movies not only question the presence of America in Japan after the war, but also how Japan was trying to hide its own war crimes and imperial past. These were filmmakers who were not afraid to reckon with these histories.

I was amazed that creatives at the time were taking on this project of confrontation in every country: Fassbinder in Germany and the French New Wave. This interest also influenced how I viewed the world at the time.

For example, in 2011, when the Fukushima nuclear accident happened, it resulted in the nuclear meltdown that sparked the biggest protests in Japan that I had ever seen in my lifetime. The films I was watching were directly influencing my response to the politics of the real world and vice versa. Then, of course, I took this perspective to the US, where I went to university. This was in the 2010s, when there were these waves of political movements happening: Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and Trump’s presidency. All of those were influencing my cinema intake, and everything was working in harmony together that way.

NS: I haven’t been able to articulate it well until now. It’s a bit difficult because I don’t subscribe to the idea that art or artists should be making work that’s functional towards a specific goal. I think Happyend is personal more than it is political. Happyend includes politics, but that’s because I was drawing the emotional state of the characters from where I was in my early 20s, which is when I was having my political awakening.

I was mainly making Happyend as a tool to capture and archive emotion. It’s a very specific kind of emotion that is so hard for me to articulate in words. It’s a mix of nostalgia, but also this knowledge that you can’t return to that nostalgia. The only way you can return to those past moments is by reaching out to those friends that you had on those days, but you’ve since lost touch with them because you disagree with them … I wanted to reconstruct all of these complex, hard-to-articulate feelings. Film happened to be the best medium.

On a different note, Japan, as a country with an imperial past that was then occupied by the US empire, to this day is essentially a client state. It outsources its defense capabilities to the US and is completely tied to the US. What this has done is promote with Japan a kind of victimhood mentality as the first country that was bombed with atomic weapons.

That was the primary narrative that I grew up in, especially because my grandfather is from Hiroshima. But if you look at history and talk to others like Koreans or Chinese people, you gain a different perspective. The day the atomic bomb dropped was a day of liberation for Korea. The war ended the week after. Right now, Japan is kind of reverting back to a desire towards an imperial past and also historical amnesia, as you’ve mentioned.

NS: I’m glad they came across as fully realized characters to you. I’m also happy you started our conversation by asking questions that got deep into politics. Audiences in the west typically don’t see that the disparate elements of the film are actually the same. A lot of people separate the characters from the authoritarian, surveillance, and foreign backdrop… in reality, it’s all fundamentally about colonialism.

Just to illustrate this a bit, when Korea was a colony of Japan, a lot of Koreans lived in Japan either as forced or voluntary laborers. In 1923, there were tons of Koreans living in the Tokyo region, and there was a big earthquake that happened. Because of this resentment that was building up towards Koreans, Japanese citizens spread rumors that Koreans were poisoning the wells in the aftermath of the earthquake. This led to the genocide of 6,000 Koreans in Japan.

The Tokyo governor used to always send letters of condolences on the day of the memorial. That was a normal thing until the current administration, whose governor has stopped sending those messages. Around Japan as well, these memorials, grave sites, and statues are being taken down.

After World War II, Korean and Taiwanese people were all considered Japanese; as subjects of the Japanese emperor, they technically should have had citizenship. Yet the very last decree that the Japanese emperor put in place before he lost political power was the Foreigner Registration Act, which stipulated that all the former subjects in these colonies had to register as foreigners. That’s still the current political system in Japan today where people in Japan are separated between Japanese and non-Japanese.

We’re entering a period of historical amnesia where now, both the populace and government are blaming everything that’s presently “wrong” with Japanese society onto foreigners. There’s extreme racism and xenophobia against foreigners, but no criticism towards the US military that’s causing havoc in Okinawa. The scapegoats are the foreigners.

We’re told that in the next few years, there will be another earthquake, and it will be the same one that happened in 1923 because they come in a hundred-year or so cycles. Anytime there’s an earthquake rumor, if you look at Twitter, you’ll see people joke that it’s the Koreans who are poisoning the wells. If this is the situation we’re going to be living in, what will happen to those foreigners living in Japan when another earthquake happens?

NS: I drew from my own life for that. I have a close-knit group of friends who I’ve known since fourth grade, and we always hug each other and are on top of each other [laughs]. The very first thing I had the cast do in order to help them get used to each other was to have them sit across from each other in pairs and look into each other’s eyes. That sounds silly, but it really does remind you that the person sitting across from you is a person. We did other ones, such as having one person walk towards another, and if the other person was feeling like the other person was entering their safety bubble, then they would just say, “Stop.” Everyone would feel each other’s personal space in that way, and then at the very end of the workshops, we would all hug each other goodbye.

Then the actors just started hugging each other, so even without me prompting, they would just do a little dap and then leave. Those kinds of things are really small, but I think they add up to a comfort that they had around each other.

NS: Unfortunately, satire in cinema is so difficult because reality goes way beyond anything that would be deemed realistic within a film. That’s what’s happening in Gaza … there are AI systems, not too different from what is seen in Happyend called Where’s Daddy. Lavender is another one. What these AI learning systems do is way more brutal than anything that I could have ever imagined. Where’s Daddy is the Israeli surveillance system that targets those whom it deems terrorists and then waits to trigger a bomb to go off when those people return home to their families. It’s the most brutal domain in which human creativity is going.

I think the reason why the Kantō Massacre happened in Japan in 1923 is that there was a dehumanization of the Korean people. That same dehumanization is happening in Palestine. If you’re considered collateral damage, there’s no political accountability. Everything isn’t just thematically tied together, but also tied together at a policy level. If you look into the colonial policy of Japan of the 1920s and 1930s, a lot of the most important advisors to the Japanese colonial imperial government, who were in charge of colonial policy, learned about colonialism through Zionism. There was this man, Tadao Yanaihara, who was the head of what would later become Tokyo University. He literally wrote a book called On Zionism, where he talks about how Zionism was the most ideal form of colonialism and how Japan should replicate it.

So it’s not far-fetched to say these things are connected. Today, for example, there’s going to be a cybertech event in Tokyo where former Mossad and Israeli government officials are coming to talk about the latest technologies, which most likely were developed through being practiced upon Palestinians.

It’s completely infuriating … there are no words really. I think everybody should be using their influence in their domains to do whatever they can to stop this. Even though I’m not necessarily using my film itself for any political function, I’m thankfully given a platform that, when my film is screened, I get access to a hundred people in a movie theater listening to what I’m saying. So I decided I should at least use that to say something about Palestine. Other than that, I’m on the ground in Japan trying to do whatever I can when I have the ability and the time.