Meropi Peponides and Remoy Philip on Performing the Revolution

When theatermaker Meropi Peponides and Beto O’Byrne landed in Delhi in 2018, their primary aim was to connect with fellow theater artists in India. But from this initial seed of solidarity-seeking branched a network of theater practitioners around the world, from Delhi to Jenin to California, whose radical and resilient approaches to public performance fought to advance freedom and give voice to the people.

Collaborating with Remoy Philip at Bad Coolie productions, Peponides knit these practices together in a four-part podcast, Performing the Revolution, which debuted this past October. Featured are Jana Natya Manch (Janam), a 50-year-old street theatre company that performs for India’s working class; The Freedom Theatre in Palestine’s West Bank, where kids fight to define who they are and what they dream about amidst a decades-long occupation; and El Teatro Campesino’s legacy of agitating during the historic California grape strikes.

“The artists featured in this series stage short, biting, satirical plays on picket lines, at factory gates, in refugee camps, and in the beds of trucks,” describes the podcast’s about page. “When India’s trade unions needed to mobilize a million workers, Janam’s plays helped rally the masses. When César Chavez and Dolores Huerta led unprecedented strikes in the California farmlands, El Teatro Campesino brought their stories to the picket lines, gathering support for unionization efforts.”

The Amp’s editor, Shannon Lee, spoke to co-executive producers Peponides and Philip in advance of the podcast’s release to discuss the process of telling these stories, their own relationships with performance, and whether theater can be at the heart of political change in today’s world.

Meropi Peponides: We met Sudhanva in Delhi in 2018. My partner Beto and I were there with our company, Radical Evolution, trying to understand the landscape of what theater looks like in India. We had received a grant to go and connect with different theater artists. I knew somebody from grad school who had gone back to Delhi and started a theater there. We initially connected with him and he connected us with half a dozen other people who knew a dozen others. We followed this network of theater-makers across India.

One of them told us we had to connect with Sudhanva and Janam. That was the first time we’d ever heard of them. We found our way to his bookstore in Delhi, Mayday Bookstore, which he runs alongside Studio Safdar. We talked for three hours. He told us the entire story that’s in the podcast—about Safdar and what happened to the theater group on January 1st (1989).

Six months later, Sudhu found himself in New York. In continuing our conversation, we thought it could be a great idea to apply for a grant to bring Janam members to NYC to do an exchange where both our companies would get to collaborate? We got the grant to make this happen in February 2020—one month later, COVID-19 shut everything down.

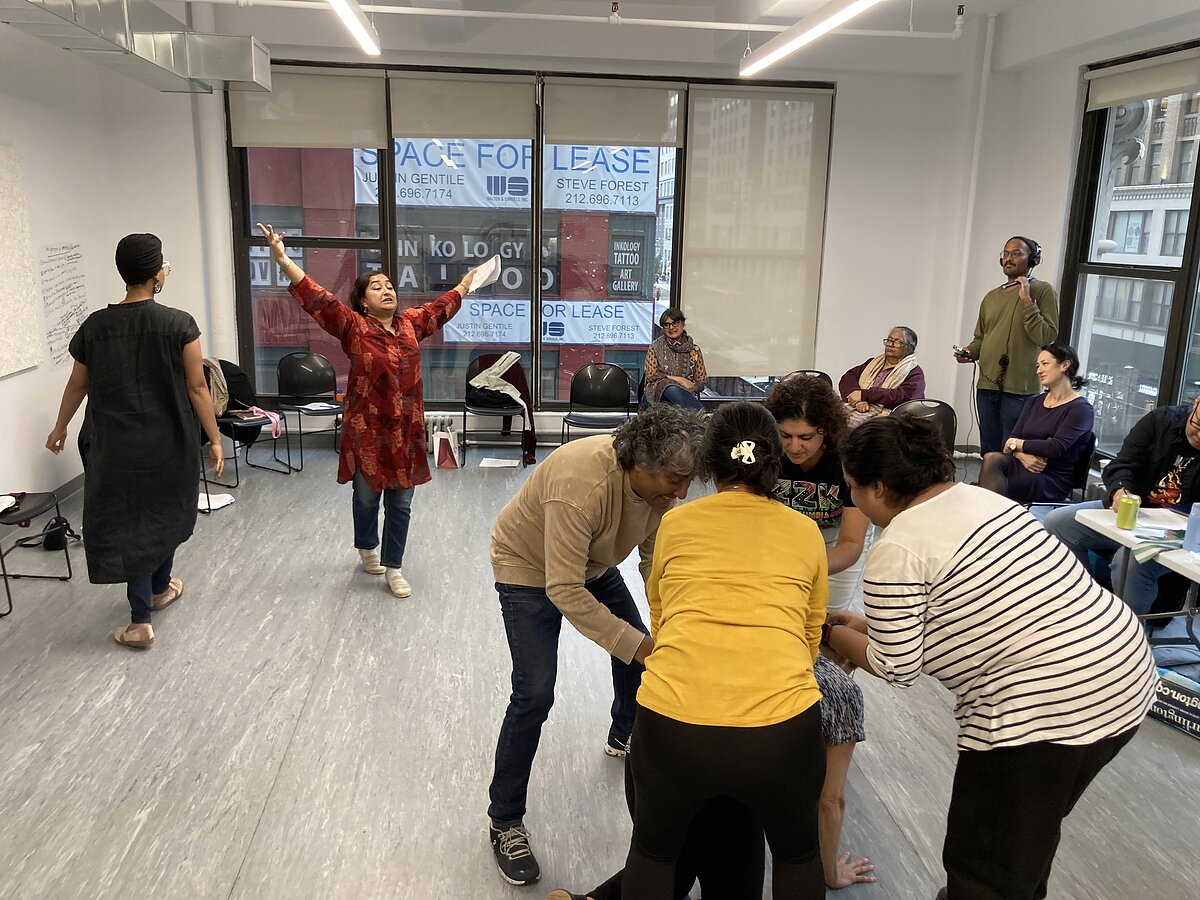

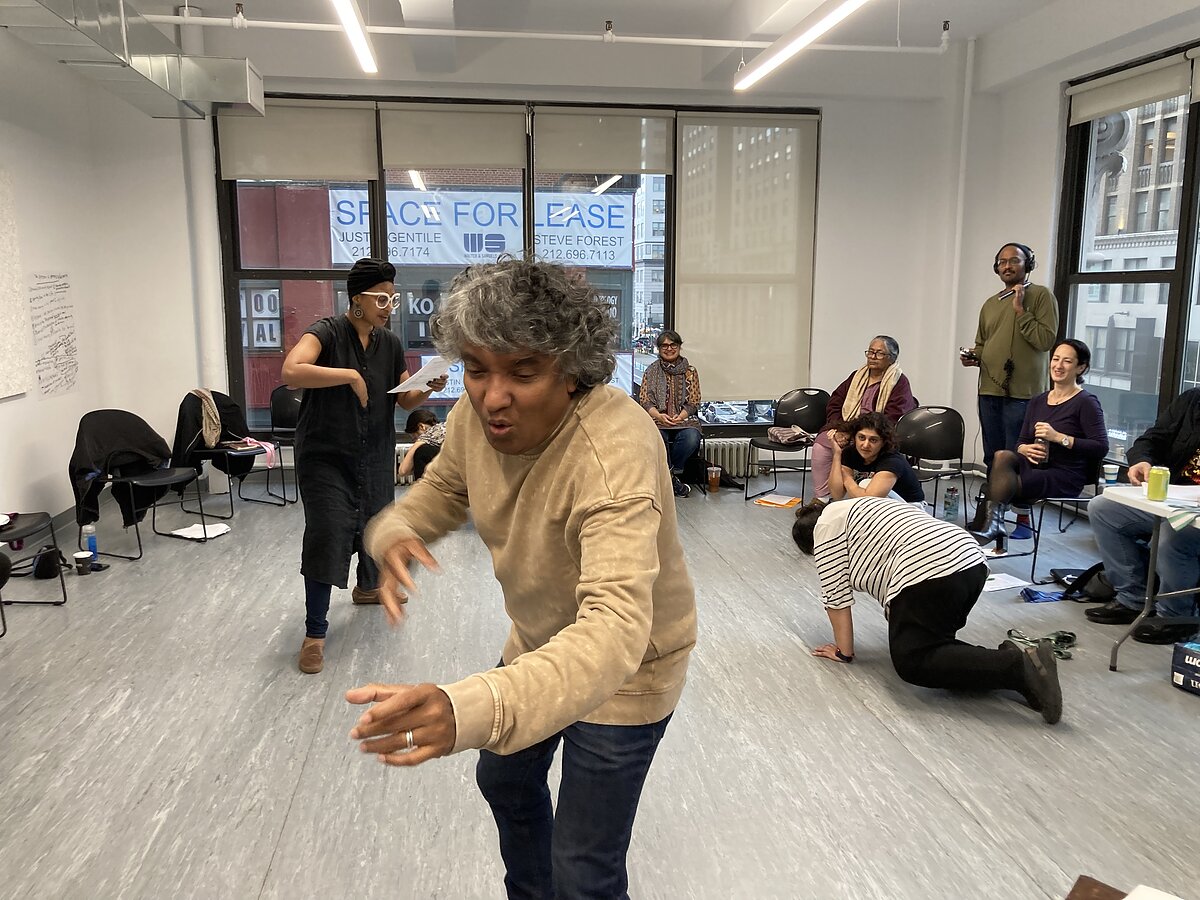

We were finally able to make the exchange happen in fall of 2023. Five members of Janam came to New York and we collaborated on a short theater piece called A People’s CUNY. We also reached out to Remoy who we knew from past projects to collaborate on some sort of documentation of this exchange.

Remoy Philip: When we met the Janam members at the airport, I was very scared; these uncles and aunties are so badass! I’m just this shy South Asian boy and I was like, God, what am I doing? But after talking to Mala, who’s in the first episode, I also realized that these were my people—the uncles and aunties I never had.

I wasn’t sure what this was going to end up becoming. I was sitting in the rehearsal studio as these two companies came together to create this performance, documenting the process and their stories.

RP: I’ve been lucky to have done some other work in Palestine, in the West Bank specifically. One of the big shows I worked for was called Not Past It, which was a weekly history show that ties the past to the present moment.

In those initial rehearsals and conversations, I could see how Janam’s work and Safdar’s story connected with Palestine. Sudhu and other members of Janam were talking about their relationship and collaborations with Freedom Theater in the West Back—this was all happening right after October 7.

Despite thousands of miles, borders, and oceans, there’s this intrinsic connection. This felt like such an extraordinary opportunity to tell this story. It felt like we had to do it.

MP: Having more audio experience, this vision was clearer to Remoy than it was to me. In the beginning, I was like, How do we shape this series? But pretty soon, it became clear that the people and the real life stakes behind the work were so much more interesting than the process of us creating the play itself. Like, yes, there’s the work that happens in the rehearsal room. But what does that mean in the wider world?

Just to get yourself into the rehearsal room involves some really intense stakes. Getting visas for the Janam collaborators was so tenuous; we had no idea if we were going to get through. Mala almost wasn’t able to make it here due to health concerns. One of Sudhu’s offices was raided by the Delhi police. Similar to what’s ratcheting up in our country right now, Janam’s been living with this kind of authoritarianism for about 10 years now. Just to be able to cross borders to be in collaboration with each other at this moment felt really important to highlight.

MP: My partner Beto and I started Radical Evolution in 2011 in part because we were not seeing the type of artistic home that we were hoping for in the New York City theater landscape. We were both in a place where we were really interested in breaking down perceived categories.

We were also questioning this idea of these really narrow specializations that we were being trained into in the theater industry: for example, if someone trains as a lighting designer, they will only ever get hired as a lighting designer, and will never be a part of the artistic process in any other way. That felt so strange and unnatural to me.

We were really interested in creating a space that thought expansively about the way people express themselves.

There was also this way institutional theaters were operating that wasn’t for us. We wanted to lean into this idea of evolution that would allow us to constantly iterate and change. We’re always going to be figuring out new systems and structures as a founding impulse. Since then, we’ve made plays, concerts, podcasts (this one is our second), and publications.

We’ve also been very interested in bringing performance outside of traditional theater and performance spaces—to come to where the people are.

RP: Bad Coolie really just came out of a desire to make dope shit before I die. I wanted to pay homage to Coolies as a term for the indentured servants and slaves of Asian descent that were brought to the Americas—to reclaim that term and ask what it means to be a “Bad Coolie.” It’s a tagline for collaborators that are doing our own labor and making work for ourselves. It’s a bit of a fuck you.

In this project, I was so inspired by Mala and Sudhu as these rebel pioneers. They’re like the real-life Brown superheroes I was always looking for growing up. I also can’t emphasize enough the work of all the volunteers involved in Janam. They all have day jobs and still commit to meeting every day. It’s so inspiring and getting the chance to tell their story is an amazing opportunity for Asian Americans to engage with more stories like these. We exist!

RP: Towards the end of our collaboration with Janam, we had a work-in-progress preview at the People’s Forum that also included a Q&A. Someone in the audience, an American, was astounded that they met every day.

And they were just like, “Yeah, we meet every day because we believe in this and we want to fight for the people.” Of course, it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison. There are so many differences between the US and India.

MP: Sudhu and Janam used really specific phrasing when he asked the folks from PSC, the union we were collaborating with, to comment on the play. He didn’t ask whether they liked it. He asked, “Is this useful to you?” That was such an important thing I learned.

That has been such a North Star for our crew. It puts all notions of ego, artistic vision, etc to the wayside. The aim is to be useful. Now, to be clear, for the work to be useful it also has to be a really good show! But if we’re going to be useful, we need to ask where we need to show up and when and in what context? And let that be the thing that fuels our work.