Sheida Soleimani on Creating Political Poetry Through Images

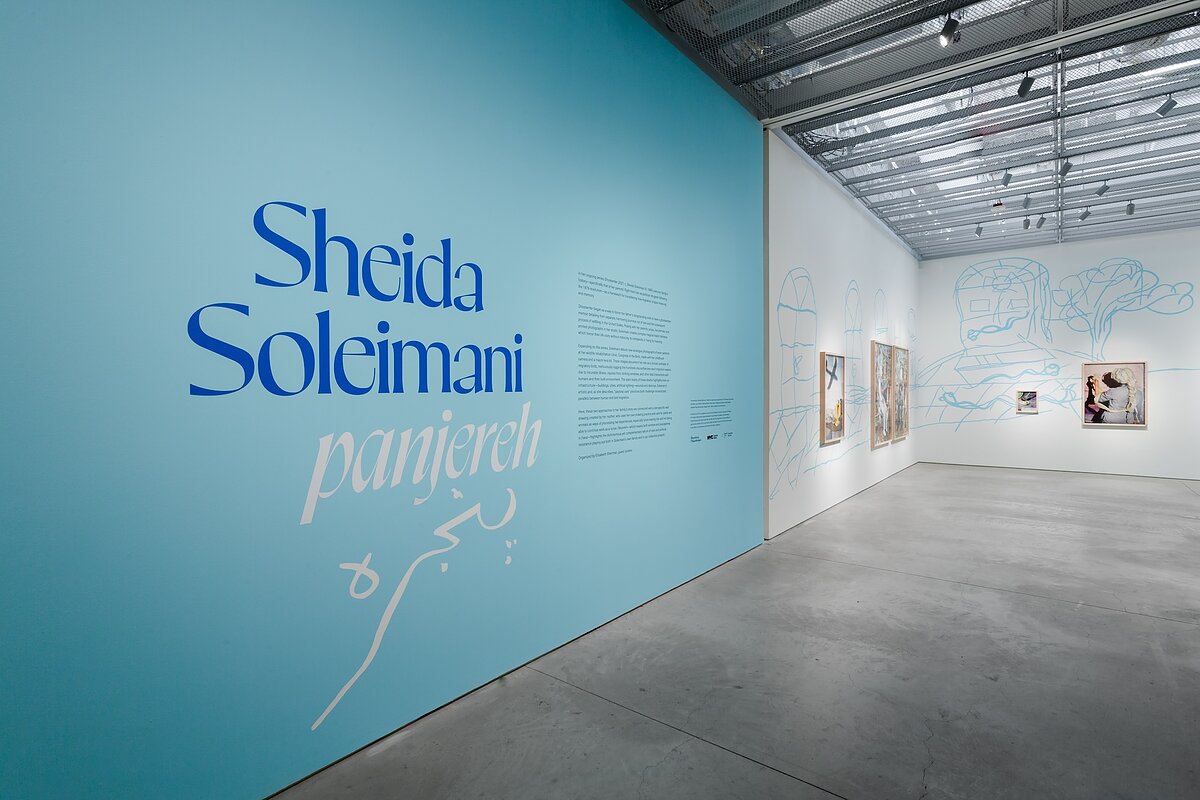

Artist Sheida Soleimani is a poetic voice, persistently political, and ceaselessly caring. Known for her elaborate and deeply playful tableaux photography unpacking the political dynamics between the US and the Middle East with her signature wit, Soleimani is also a courageous activist, a caring educator, a committed bird rehabilitator, and a joyful collaborator. Her current exhibition, “Panjereh”, on through September 28, 2025 at the International Center of Photography (ICP), centers a new approach in her politically engaged practice.

In this exhibition, the Iranian American artist turned her lens to her own family history. In doing so, she deftly engages with all the nuance and intimacy that such a practice requires. Featured heavily in the exhibition is her recent series, “Ghost Writer,” a deeply layered body of work born out of a collaboration between Soleimani and her parents, both of whom are Iranian political refugees.

Within “Panjereh”, these images carve a path for us to enter her parents’ story, reflecting on lives saturated by incarceration and forced migration; lives forced into a suitcase. These deeply poetic works tell a personal account of the Iranian Revolution and the brutality of suppression. Though she never shies away from the hardships of her subject-matter, Soleimani renders a world where birds, snakes, plants, and people protect one another—traces of her lifelong commitment to care work.

Speaking via Zoom from her home in Providence, Rhode Island, Soleimani told me about birds, the affects and aftermath of the Iranian Revolution, poetic ambiguity as a form of political subversion, and adapting to new environments while in exile.

SS: I get a lot of animals dropped off here—people in Providence know where I live, so if they find a bird, they’ll often just leave it at my door without saying anything. I’ve opened my front door to boxes of chickens, parakeets, finches, you name it.

Last year, someone left two parakeets stuffed in a bag that said “Happy Bday”. I got a little attached, so they stayed, and are named Happy and Bday. I also live with two ravens, two crows, and a blue jay who are all educational ambassadors for Congress of the Birds. They’re non-releasable and help us teach the public about wild bird care and conservation. Alongside them are about 20 chickens, eight ducks, and four guinea fowl.

YA: [Laughs] I expected nothing less, but I’m also delightfully surprised! I would love to start our conversation by focusing on your current significant body of work, “Ghostwriter”. I had come to know your practice through its clear political engagement but this body of work is different. Sometimes you discuss the title as a reference to your father’s desire to have someone write the story of your parents’ lives, not only as immigrants, refugees, people in exile, but also as two politically active people, as two who have experienced what it means to be political prisoners.

In this ongoing body of work, you really delve into the power of storytelling. While collaborating with both of your parents, you carry their stories with so much care, affect, and complexity. And you do this with your unique photographic voice.

SS: I’m really lucky to be so close with my parents; storytelling has always been central to our relationship and how we communicate. As a fellow Iranian, I think you’ll understand how deeply ingrained that is culturally. But growing up in the Midwest, I noticed how Americans often expect stories to be direct, especially when they’re trying to access unfamiliar experiences. There’s this urge to frame things through trauma, to hear what’s good or bad, right or wrong, without much room for nuance.

In school, when I’d say something like, “My mom was in prison,” there was no framework for others to understand what a political prisoner was. In Ohio, being in prison meant drugs, theft, or murder—there was no room for the political, for the complex. So storytelling became my way of building bridges. Show-and-tell would turn into me explaining the Iranian Revolution. My parents, both activists, were always telling me their own histories: my mom working in a leper asylum or treating Kurdish victims of Iranian attacks; my dad witnessing his friends being hanged. These weren’t exceptional stories in our community—they were part of how we lived, part of how we survived. That’s what drives “Ghostwriter”.

I’m drawn to magical realism as a way of resisting this Western demand for clarity. In [Gabriel Garcia] Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, for example, time folds in on itself—characters live across centuries, or maybe they’re ghosts. That ambiguity is political. It destabilizes the reader. I want my work to do the same: to challenge viewers to engage differently, to resist simple readings, and to reassemble fragmented narratives on their own terms.

YA: And we get to witness this so clearly in your current exhibition, “Panjereh”, which means window in Farsi. There are so many incredibly powerful pieces from “Ghostwriter” that come together in this show. There’s the titular work, Panjereh (2022),which shows your mom in a make-shift tableaux of solitary confinement, made of scraps of paper.

Nearby is Khoy (2021) which features a poem your mom wrote while she was incarcerated:

نیست بیدار کسی

نیست فریاد رسی

در سیه چالم و اینجا نبود هم نفسی

همه بیدار شوید

همه هشیار شوید

همه درهای قفس بگشایید

همتی باید کرد

از قفس باید جست

از قفس باید رست

I was shaken by how beautiful and powerful her poem is. I had heard the stories you have shared of your mother’s time in prison. They are horrific and, unfortunately, familiar to me, as many Iranians of that generation had similar experiences. But the poem shook me. The voice of your mom in her poem is so full of hope, in a nearly radical way. In the last lines, she nearly demands:

“From this cell, we must escape,

From this cell, we must be freed.”

SS: I really appreciate that you were able to read the poem. So many American viewers have said, “I can’t access this work because it’s not in English. Do you have a translation?” And sure, I can give a rough translation—but so much is lost. Farsi holds layers of meaning; even something as simple as the word for asparagus, marchoobeh, literally means “little snake stick.” That kind of nuance doesn’t carry over.

That complexity also ties into the show’s title. The word panjareh holds so many meanings for me. I started thinking more seriously about windows during the first Trump era—about borders, about what we can and can’t access, about being held in or out. At the same time, I was thinking about the window in my mother’s solitary confinement cell. She drew it constantly, from memory, over and over. Even at restaurants, when they’d give me crayons and table paper as a kid to draw with, she’d take them and draw that window. It was situated far above her head, letting in a sliver of light from left to right. She’d warm her hands in the sunlight on the wall. It was her only access to the outside world. That window was never just a window—it was a boundary, a portal, a torture device. It offered a glimpse of freedom while enforcing her captivity.

That layered meaning of “window” extends into my wildlife rehab work. Window strikes are the number one cause of wild bird death, aside from outdoor cats. Migratory birds—some flying from South America to New England—navigate by starlight. City lights scramble their stellar cues, drawing them down where they can’t distinguish glass. Because birds are tetrachromats, they see far more than we do, but untreated windows are invisible to them. These clear, beautiful windows we love become deadly traps.

So for me, “Panjareh” isn’t just about a view or a portal. It’s about violence disguised as transparency. It’s about how even something that feels full of hope can be a mechanism of harm.

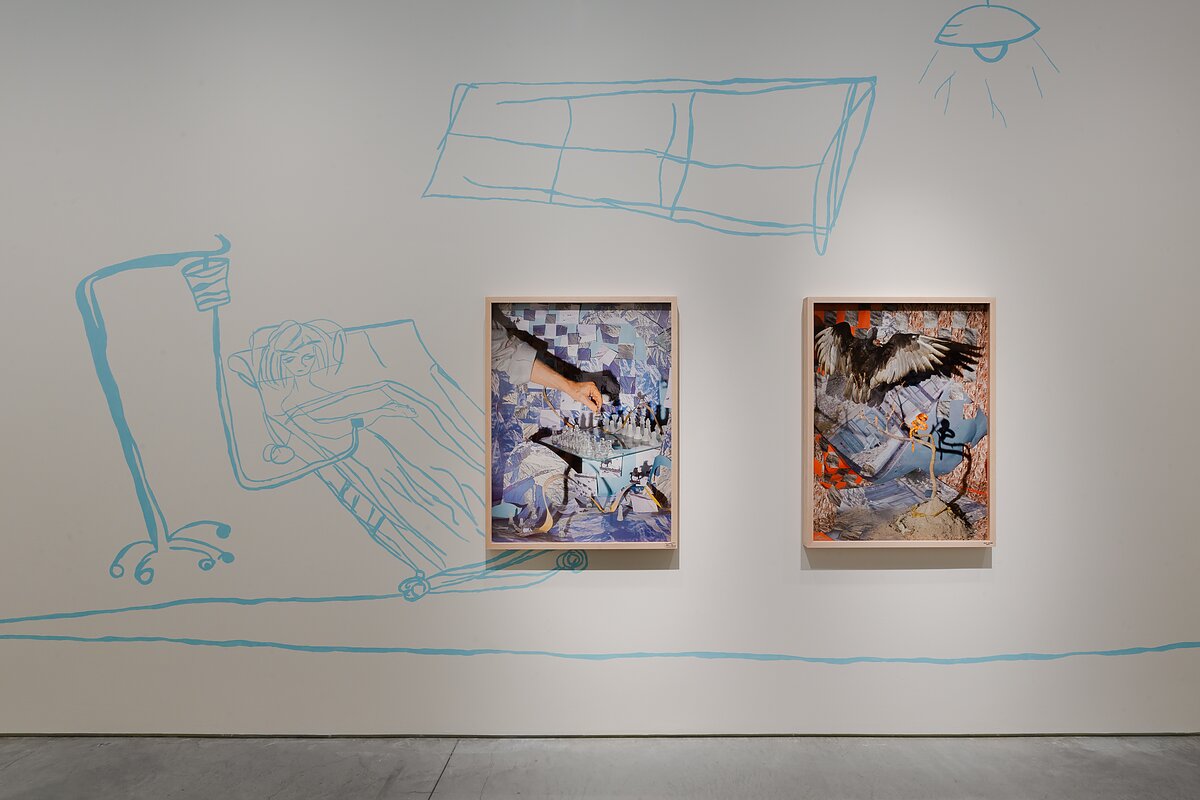

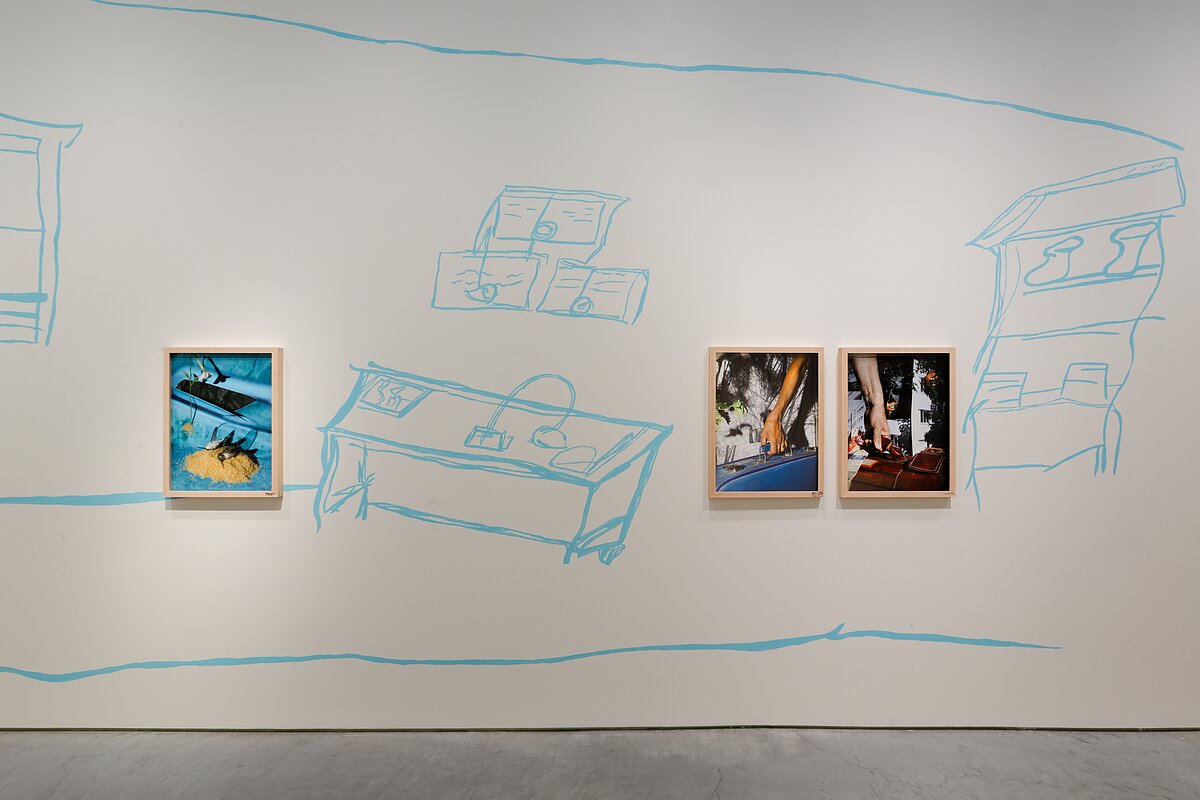

YA: An aspect I found really moving about the exhibition are the drawings that cover the walls of the gallery. This is a gesture you have used in other exhibitions. I was reading about one of the earlier iterations, and you had mentioned that the line drawings are your mom’s. They recall her childhood home, which was also where your father went in hiding to escape prison. You talked about how her drawings have been her way to ask you to remember this space, though you have never—and might never—see it in person.

In this show, the drawings range from fragments of homes to hospital beds to bodies and organs. Going through the exhibition, I kept thinking of the drawings carrying us through the space; their lines are both an intimate map and a form of remembering that feels significant in your work.

SS: At ICP, I was thinking a lot about how to break up the space—the hallway and the main room—and how to differentiate them. It reminded me of the two spaces my parents moved between: the home and the hospital. That duality exists in my life too. My home holds the personal, the artistic. The wildlife clinic holds the care work. I wanted the exhibition to reflect that split.

I’ve been increasingly drawn to building environments in exhibitions. For me, each photograph functions like a screenplay. There’s a sense of staging: who’s the protagonist, the antagonist? Where’s the light coming from? Who’s entering from where? I can’t stand exhibitions that are just pieces on a wall. People always say I’m a maximalist, but it’s not just about excess, it’s about context. A strong work should stand alone, yes, but I also want to resist this need for clean timelines or didactic histories. That’s where the drawings come in. They’re my way of creating a timeline through gesture and through space, not through dates. The house my mother lived in is gone, but its imprint remains. The hospital she worked in no longer stands, but its bones are still there. These drawings hold the past, present, and future at once. Like oral histories, they’re a form of visual storytelling.

YA: I was also thinking about your unique relationship with sculpture. For so long, I had thought about sculpture in relation to the suspense of utility, or even in relation to rituals and the power object.

But there is something else happening with the makeshift objects here. Years ago, a conversation with the artist and educator Setareh Arashloo opened my eyes to a different take on this medium. Arashloo’s work is also often inspired by her mother’s experience as a political prisoner. For her, sculpture is a way of recalling the forms of making that happen during incarceration—sculpture as a mode of spending, measuring, and marking time. Sculpture is an intimate relationship with a few objects that become part of everyday life.

I was thinking of this form of sculpture as a witness, and then I was hooked by your piece Behesht Zahra (2023), referring to the famous cemetery in Tehran. Here, your father sits surrounded by open graves, unmarked, scattered, fragmented. As you note in the wall text, Behesht Zahra is a notorious reminder of all the political prisoners of your parents’ generation that were brutally executed and then secretly buried. The government desecrates their burial sites to this date. Amidst them, he sits on the carpet that he had once carried with him throughout his journey, fleeing Iran.

I stood there, thinking of the hand-made, the object as witness, thinking of grief, and the power of your making.

SS: The death drive is real—historically, in art, and in life. For my parents, as immigrants who survived so much, there was a pressure to build something from the wreckage. But they never allowed themselves to grieve. When they told me their stories, it wasn’t about passing on grief, it was about passing on reality. Grief, in that context, felt like a luxury. It’s something you only get to do when you have time, when survival isn’t the priority.

I remember starting to teach in 2015, when I was 25, and hearing my students talk about self-care. At first, I dismissed it—like, what are these soft kids talking about? But then I realized I’d internalized this hardness. My father would say, “Why would I grieve? Life keeps moving.” That urgency becomes a way of life. There’s a line in the show: موجیم که آسودگی ما عدم ماست (“We are the wave that ceases to exist even when we reach the shore”). Rest becomes a kind of death, a letting go that’s too dangerous to allow.

My mom still talks about everything she went through, but she hasn’t grieved it. It’s always present-tense. That’s what trauma does—it collapses time. For me, I don’t carry their grief the same way. I’m a witness, a vessel. It’s not traumatizing because it’s so deeply embedded. It’s just life.

That’s why I build the work the way I do. These are layered, complex realities. The installations, the props, the characters, the sculptural components, are meant to resist the flattening that photography can so easily do. Grief, memory, and survival are not linear. They collide and live in the same space.

YA: I found that line at the bottom of a frame of one of your last pieces. Though I already knew the poem, that line has been haunting me. In Farsi, there’s this emphasis that if we are to be the waves, calm will negate our existence. It’s so hard to stay with that. Especially now, as educators, I keep thinking that our parents went through all these histories when they were so young. They were college kids, the age of most of our students. Suddenly, I really want them to be able to rest.

This body of work is explicitly rooted in your collaboration with your parents. But far beyond that, collaboration has been continuously present in your practice. You are always mentioning friends and mentors in your interviews. As it happens, I first learned of your work through one of your friends/collaborators, Paul Soulellis, the founder of Queer Archive Work.

SS: He lives one door down! When I started teaching, I had no idea how messed up academia really was. My first job was as a diversity fellow at RISD, and while I’d been a student in academia, I was more blissfully unaware back then. Once I was on the other side, I saw how students were organizing—mobilizing against institutional harm—and it reminded me of my Baba, who always said students were the ones leading the charge, part of the intelligentsia pushing for change from within.

But it also made me think about who gets left out—who doesn’t have access to these spaces or conversations. I noticed this urgency from students, believing that protest should lead to immediate change. But real political change is slow. It made me rethink what protest even looks like. It’s not just marching in the streets—though that matters. It’s also care work, storytelling, and collaboration.

For me, activism includes listening, holding space, telling the stories of those who’ve been silenced. Change doesn’t come from one person, it comes from collective action and care. That’s at the heart of my practice: building relationships, sustaining resistance, and expanding the idea of what protest can be.

YA: In all the photographs, there is a unique small stamp at the bottom of each frame. Some of the stamps are replicas of postage relating to different times and geographies. I think one of the last stamps was the poem about the waves which we discussed. It was really fun finding them slowly. It kind of made me think of every image in this work as a letter; with the postage, I began to think of each wooden frame as an envelope.

Walking between these works in the current exhibition, I also started to notice that your human subjects are notably alone. Your mother and father are almost never seen together in these photographs. Their correspondence and the desire for touch—for an embrace—feels so deeply present. One of the last pieces of the show is the triptych, Interference (2025). In it, each of your parents holds one side of a makeshift phone to their ears made of a food can and wires covered by your mom’s snake skins. But the wires connecting the phones are cut by the frames. Pinned to the wall keeping them apart is a small frame that holds a tender photograph, a simple white flower.

SS: I think there’s so much of this. We’re always trying to tether narratives—to time, to place, to something fixed—but they rarely stay that way. Like there’s this little pot: it moves from one space to another, and in doing so, its identity shifts. Does it become something new in a different country? Does it need a new purpose?

That ties back to sculpture for me. When does something become sculpture? Is it when it stops being functional? Or when the thought behind it begins to function differently? I’m interested in those thresholds—objects that carry layered meanings and evolve as they move. The same goes for storytelling. Communication is often fractured and nonlinear. Stories shift depending on who tells them, when, and where. They’re unstable, full of interference, and constantly transforming.

SS: I made those pieces just two weeks before the exhibition. It all started when the museum director saw my bird photographs while I was showing work in Italy. They were just the close-up shots of the birds, no backdrops or drawings. I loved the photos, but felt they weren’t enough, not layered or contextualized. Elisabeth Sherman, the curator I began working with, encouraged me to include them anyway, saying the photos were complicated and I should give myself more credit.

Still, I felt the images weren’t quite finished—they lacked context and story. The birds weren’t placed anywhere. Most had been maimed by window strikes. At the same time, I was cataloging blurry negatives from my mom’s very first roll of film, mostly shots of the sky. I decided to place the birds back into the sky using screenprints of sky crops beneath the photos. But even that felt too simple, too linear, like the birds were dead and just pasted back where they belonged.

One week before the show, I asked the screen printer if he could print some of my mom’s drawings on top of the bird prints. Thankfully, he agreed to give it a shot. When I saw them layered together, I knew this was what I needed: a kind of codex where the images and drawings speak to each other but aren’t immediately clear. These drawings echoed those on the walls, creating a larger family. I was nervous—they felt so incredibly different from my usual work. But once on the wall, the language aligned perfectly, and they made sense with my in-studio tableaus.

YA: There is something grounded and grounding about your work that feels significant. Mainly because it is rooted in a history so full of interruption and social trauma, it is almost as if you have this power to let us think about and feel these moments again and be safe while doing so. This is something I genuinely appreciate about this incredible show you have put together.

I’m thinking specifically of two paired photographs, Taghato (2022) and Safar (2022). In each, we see your mom and dad’s hands holding the only suitcase that they could take on their journey leaving Iran, so long ago. You can still see the tags on the suitcase. Behind each of them are plants and their shadows. In the wall text, you explain that your mother, knowing she would likely never return home, brought seeds from the pomegranate and tamarind tree her father grew in their family home. She finally planted them when she settled in America, and after all these years, she still refers to these plants to measure her time in this country, though here, in this new environment, they have been growing so slowly.

SS: They’re tiny, but absolutely beautiful. What you said really hits home—these are seeds that don’t naturally thrive here, but they still grow. That’s what being part of a diaspora feels like: being uprooted, forced from home, yet finding ways to survive and adapt. These plants have become a mirror for her, a coping mechanism. They weren’t meant to leave their original home, but someone brought them here, lovingly cared for them, yet it’s still not the same. It’s never really home.

There’s this ongoing effort to recreate home—something she’s always done, and something I’ve tried to do too, even though it was never truly mine. I started growing plants, adopting her rituals. She told me about pinning insects to the walls of her mud house, creating a bug collection she’d draw. In my first college apartment in Ohio, I did the same, pinning bugs to the wall, trying to recreate that space.

These stories and practices travel across borders—illogical, shifting borders—and try to unfurl elsewhere, even if those spaces aren’t quite right or hospitable. They become new forms of choreography, new ways of making space. Building these spaces, negotiating what’s real and what’s recreated, is something I’m deeply fascinated by.

Sheida Soleimani’s “Panjereh” is currently on view at The International Center of Photography through September 28, 2025.

—Yasi Alipour is an Iranian artist/writer based in Brooklyn. Her tactile works explore folding as a flirtation with mathematics, as traces of time, and as an homage to the intricacies of the world of papers. In her writing, research, and pedagogical approach, Alipour focuses on intergenerational conversations that happen through and within histories of erasure.