Dawn Chan and Marit Liang on Asian Counterfutures

Is it possible to be othered across time? This is the central exploration of writer Dawn Chan’s 2016 essay, “Asia-futurism,” in which she deconstructs the prevailing myth of an “Asian-inflected future.” She writes, “visions of Asia-futurism continue to be mirrored, magnified, and distorted in the Western world toward complicated ends, with complicated effects on both contemporary art production and an already troubled construction of Asian American identity.”

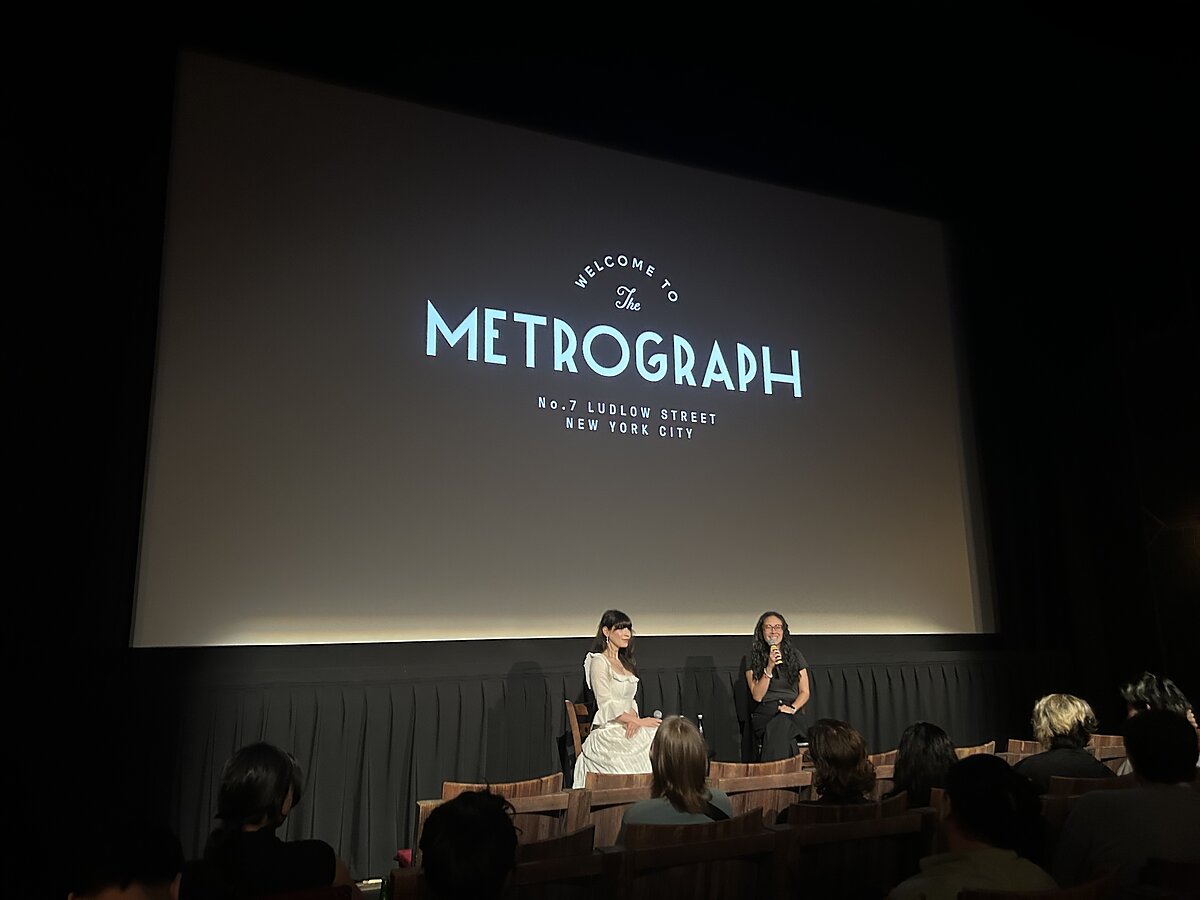

Taking Chan’s essay as a point of departure, on September 28, 2024, Asian American Arts Alliance partnered with Metrograph to present “Asian Counterfutures,” screening four films that interrogate and refute such Orientalizing habits: Sinofuturism (2016) by Lawrence Lek, Cyber Palestine (1999) by Elia Suleiman, Virtually Asian (2020) by Astria Suparak, and LA VISITEUSE (The Visitor) (2021) by Marit Liang.

Whether expressing pessimism about Asian humanity in the face of automation or a desire to escape earthly existence altogether, these four short films prompt new questions about where we’re headed. Sinofuturism, Virtually Asian, and LA VISITEUSE will be available to stream online on Metrograph’s website through November 1.

Following the screening, Chan and Liang sat down for a public Q&A to discuss the overarching themes of the program in-depth, as well as Liang’s processes and influences for her film. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Dawn Chan: Thank you all for coming. It really does feel like we are going to be beamed up in these spotlights! I wanted to thank everyone at Metrograph and Ian for coordinating this, and also everyone at A4—Danielle, Lisa, and Shannon. It’s such an honor to be here and to get to talk to Marit about her film.

I also wanted to thank the programmers for including such a diverse array of films in this program, including Cyber Palestine. I know that we can only converse based on our own lived experience as Chinese Canto- and Pacific-diasporic American creators, but I think it’s also worth remembering, given [Edward] Said’s overwhelming influence in all of this, that the little that we can address tonight is part of a much bigger and more urgent and contested conversation around what Asian counterfutures might mean.

ML: I was thinking about outer galaxies. I was thinking about the motion of celestial bodies in time. I was thinking about the way that film moves through the reel, through the body of the film camera in a cyclical and spiral nature, and sort of moving outward from that, thinking quite a bit about various forms of preservation, of memory, of which filmmaking is a central aspect.

Something I’m thinking about very much in this is my own family’s history of diasporic migration. My mother was born in Hong Kong, grew up in Singapore, [and] came over to the United States in 1965. Actually, the suitcase which is seen in the film still has the sticker from the aviation company that they used to come here. So, I was thinking about my family’s obsession with documenting themselves. I know many Asian families have a shared experience of taking lots and lots and lots of photos at family gatherings.

During this moment in the pandemic, I had no one else around. I was working completely by myself, so I was setting up all these shots and trying to find a way to think about the ways that I was using these technologies to document my own situation of isolation, et cetera, but maybe to connect that to deeper questions about preservation of memory in general, in a sort of melancholic or catharsis context.

ML: Absolutely. My mother’s family, in addition to running Chinese restaurants in Pennsylvania and in Las Vegas, supplemented their business with the import of various Chinese tchotchkes such as porcelain goods, ceramics, little figurines, objets d’art. I think my mother may have dismissed these as cheap or disposable goods.

As we saw in SinoFuturism earlier, we have this association with mass produced cultural artifacts associated with China. But for me as a child, these artifacts seem to bear almost mystic weight and a spiritual connection to this homeland that I had never experienced. There’s something about the mythic quality of these small Gong Shi-like figures—dragons, cicadas, and other non-human forms—that I found so fascinating and compelling as a child. As you said, I have accumulated and held onto these relics throughout my life. As cheap, mass produced, and disposable as they may be, there’s something about that inherent sense of mystery that they bear that makes them almost sacred to me—their connection to my family’s own history of coming to this country and a melancholic longing for a homeland I never had experienced.

So I did have all these artifacts and objects on hand. Others were ceramics that I had made myself, inspired by and in imitation of some of the objects that I grew up with. Some of these are going back in form to 1000s of years ago, from the early dynasties, but filtered through this diasporic and modern sensibility. I think all of those things were informing my thoughts in trying to paint this portrait of my own mixed race and racially melancholic heritage and background.

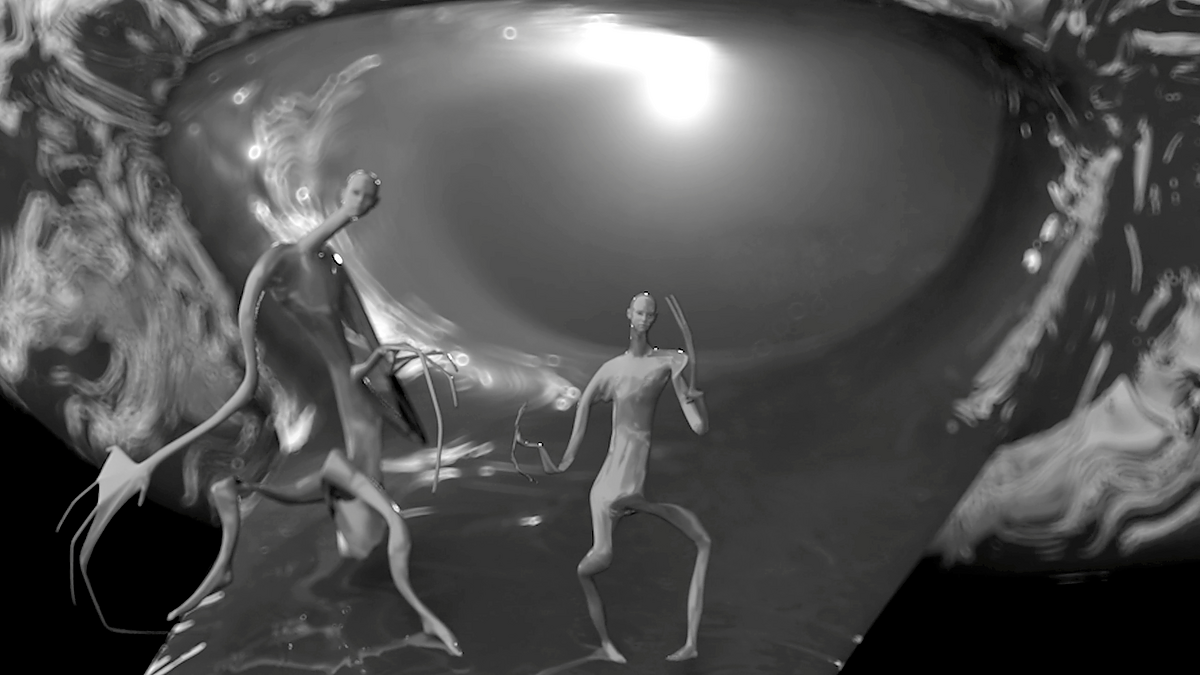

ML: That’s a wonderful question. I am thinking quite a bit about the status of the femme cyborg or femme alien presence, which is something that was referenced quite a bit in Astria Suparak’s short [film]. The way that especially Western media has constituted Asiatic femininity as something which is artificial, something that is technologically mediated, something that is—as Anne Anlin Cheng describes in her book, Ornamentalism—encrusted in artifice and almost an overabundance of decorative ornamentation.

But for that cyborg or alien femininity to be, in itself, a subject that speaks, that feels, that remembers, that desires, that loves … I don’t necessarily have any answers to that conundrum. This is something that undergirds so much of how Asian femininity is constructed, both in Asia and in the West. As a mixed race person, I feel that places me in an additional category of in-betweenness. So I think instead of trying to provide any answers to this conundrum, I am merely trying to exist within it and just embrace its internal contradictions in a way that I find hopefully both melancholic and somewhat playful.

ML: This ties into what I was speaking about earlier, in regards to this impulse to document. As a filmmaker, as someone whose life really revolves around recording technologies, there’s some association in my mind of the alien invader. But what are other motives for that alien? And maybe that would be to document, to remember.

Another piece of news that was coming out right around the time I filmed this, which is included in the film, were these sightings of so-called alien craft. And actually, those grainy pieces of footage are directly from the US Navy observing some sort of unidentified flying object moving at high speeds. There was all this speculation on the internet that this was some sort of high-tech Chinese drone. Other people were saying this is actually an alien from another star system. So I think I am trying to play into that ambiguity again, and maybe point to a different motive for the alien other than simply invading and taking over, but rather a return, maybe to its spiritual home.