What the Legacies of Past Generations of AAPI Artists Might Teach Us About Our Current Moment

Close to 50 years after her family was forced to leave their homes, stripped of their possessions, shuttled en masse to live in horse stables on concentration camps in California and then Arizona, and deemed threatening foreigners and national-security risks by the US government, the artist Rea Tajiri returned to those sites of limbo where thousands of people of Japanese ancestry were imprisoned.

Her canonical video History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige (1991) intersperses footage from those visits with scenes of Pearl Harbor and its aftermath as told through old newsreels and Hollywood clips, family letters and photos, and interviews with relatives. The work is at once an intimate road-trip movie and a sharp exhumation of the archive, an attending to the echoes of a brutal past, and an attempt at converging the cold limits of chronicled media with slippery memory to uncover a truth that is ineluctably porous.

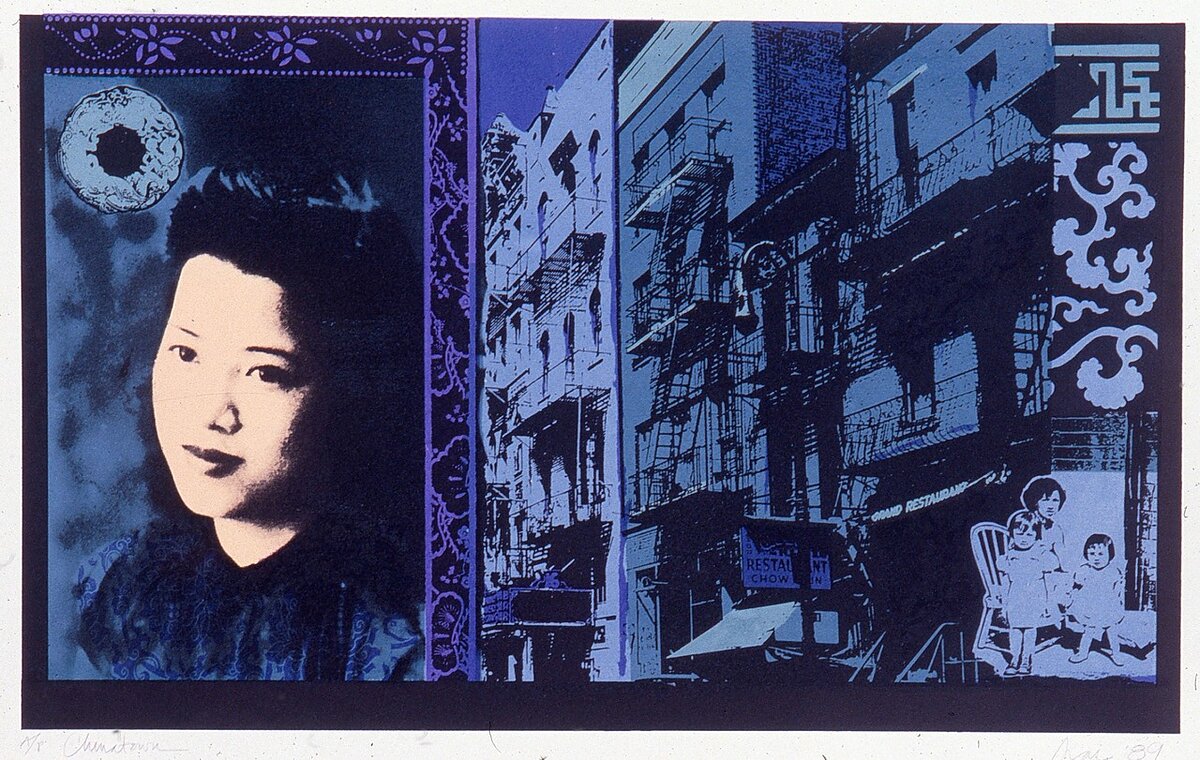

It’s this hunt—a “search for an ever-absent image and the desire to create an image where there are so few,” as Tajiri says in the video—that visitors first encounter at the exhibition “Legacies: Asian American Movements in New York City (1969–2001)” at 80WSE Gallery. On though December 20, the survey of multigenerational artists of Asian descent—overwhelmingly East and Southeast Asian—looks at how the contours of diasporic identity sharpened, blurred, and became gloriously indefinite as individuals and communities grounded themselves and fought for one another in the city.

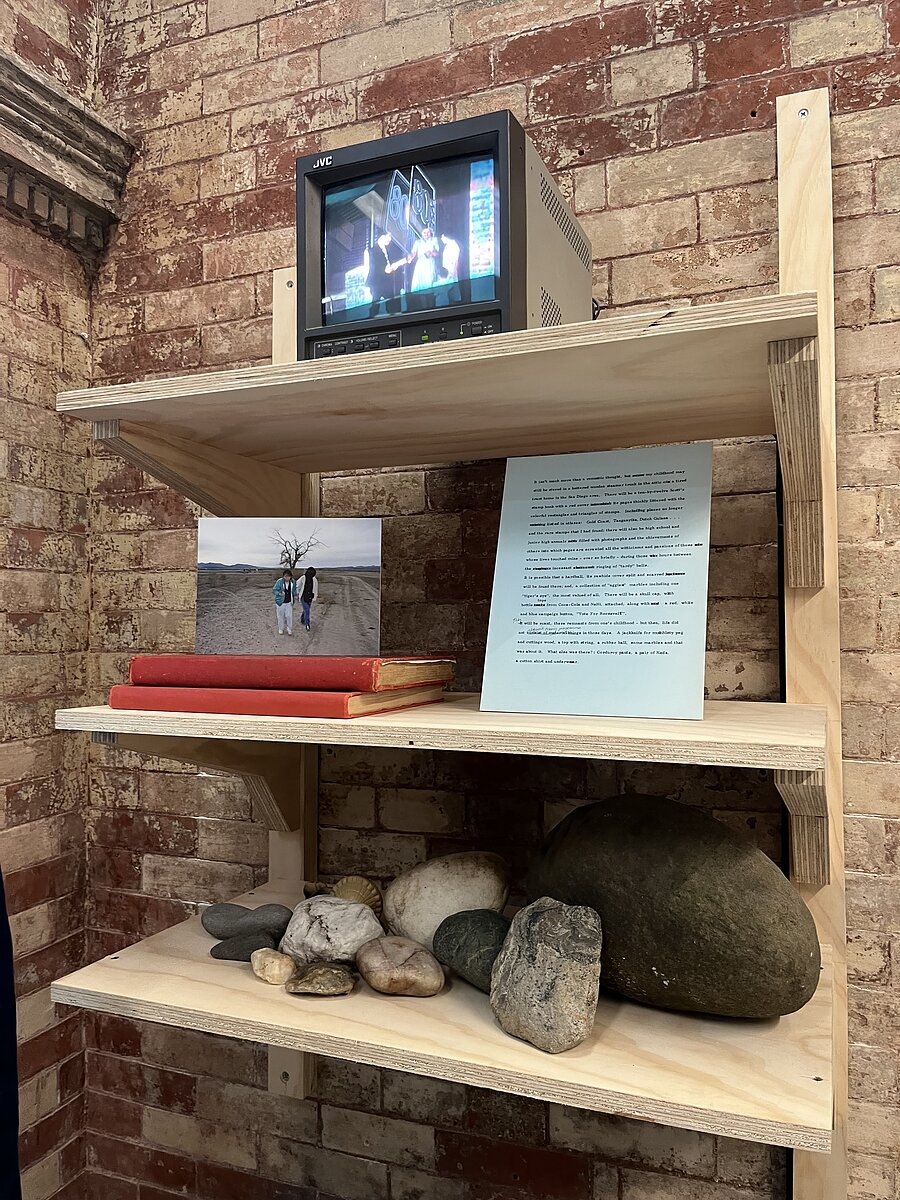

Tajiri’s video, installed in the gallery’s foyer within a newly commissioned installation, History, Memory, Vertical Stack (2024), is a subtle thread to the West Coast origins of the Asian American movement; it was at UC Berkeley where student activists coined the panethnic term amid a growing identity consciousness. It is also a reminder that the works within the exhibition build on and are in dialogue with concerns reaching beyond New York. Inspired by roadside memorials, History, Memory, Vertical Stack is also fittingly at a threshold, delineating the boundaries and in-between spaces that exhibiting artists negotiated in their respective searches for images and words, creating the language amiss in their own histories and memories.

Many exhibiting artists weren’t born in the US, a curatorial decision that immediately rejects the ideology of Asian Americanness as a birthright. Although little information about the artists’ backgrounds is provided in the concise wall text and extended captions online, snippets of who they are gradually emerge: longtime organizers in Manhattan’s Chinatown; West Coast transplants; involuntary immigrants; people with varying abilities to speak their mother tongues; people with varying relationships to their ancestral homes; self-taught artists; queer artists; dancers; poets; writers. Reflecting the research of 80WSE’s curator Howie Chen, sociologist christina ong, and art historian Jayne Cole Southard, “Legacies” is invested in scratching at the ideological neatness of “Asian American” to reveal the diverse and at times conflicting concerns of this demographic. It reminds how any neat summations of Asian Americans are just as invented as the term itself.

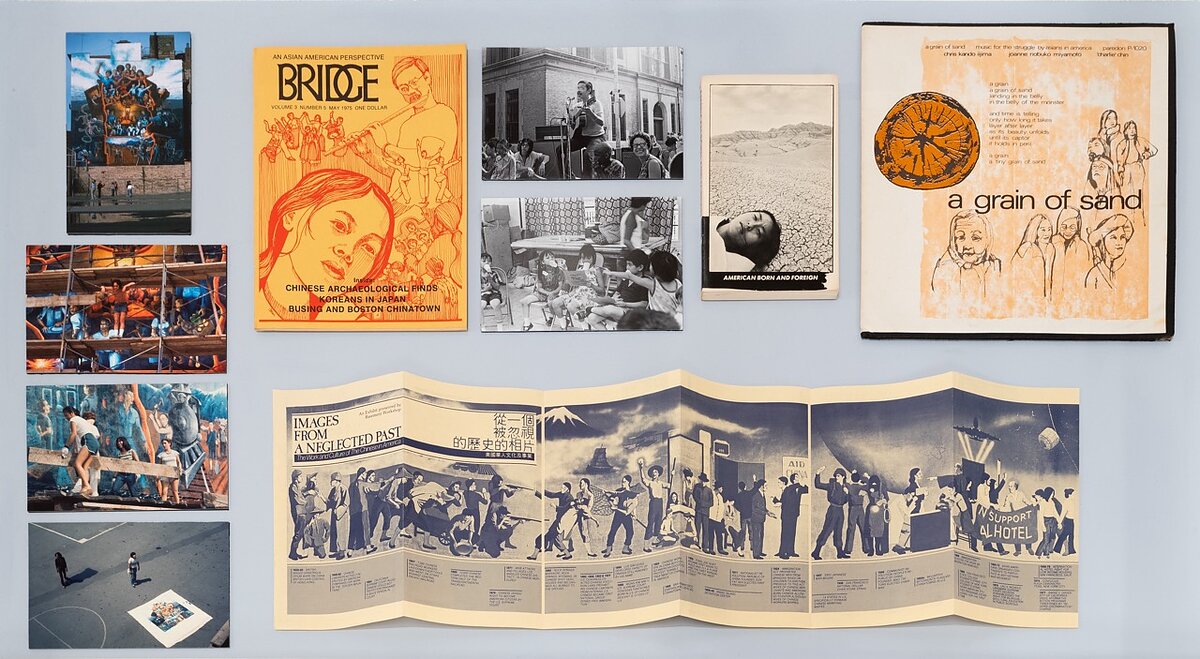

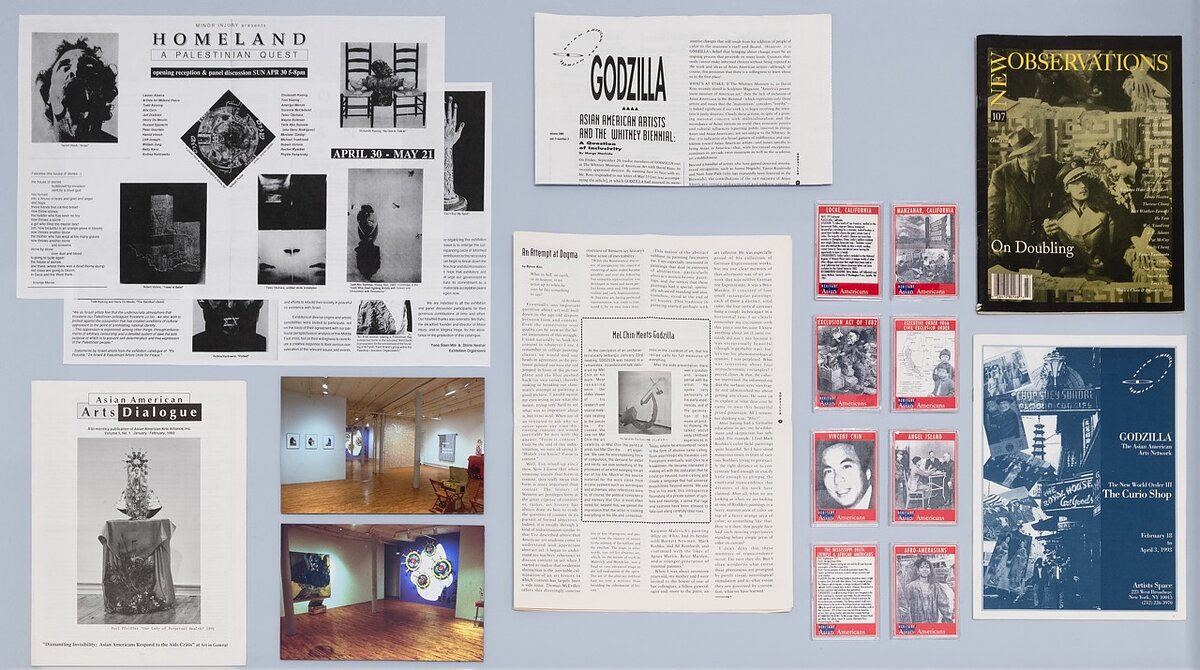

As a label, Asian American was and remains a convenient signifier of kinship around which people might unite and organize. Artworks and archival material attest to the community-building efforts of groups such as Basement Workshop, Godzilla, and the still-active Asian American Arts Centre. Basement Workshop, which supported residents of Manhattan’s Chinatown from 1970 to 1987 through social services and cultural programming, also scrutinized Americanness and “foreign” identities through its exhibitions, widely circulated publications like Bridge Magazine, music, and other creative outlets.

Many of its members were also active in the national network Godzilla that fought for Asian visibility in the established art world. A near two-hour video of interviews with dozens of Godzilla’s participants provides a dynamic oral history of the group, exhibited alongside printed matter including its letter to the Whitney addressing the museum’s dearth of Asian American representation. This vast network extended to collectives like ACT UP and the anonymous group of artists of color PESTS, whose posters calling out tokenism and exoticizing tendencies in the arts are also on view. Throughout these sprawling communities, artists were creating a cultural front beyond institutions and their individual identities, addressing issues such as the AIDS crisis to Israel’s occupation of Palestine.

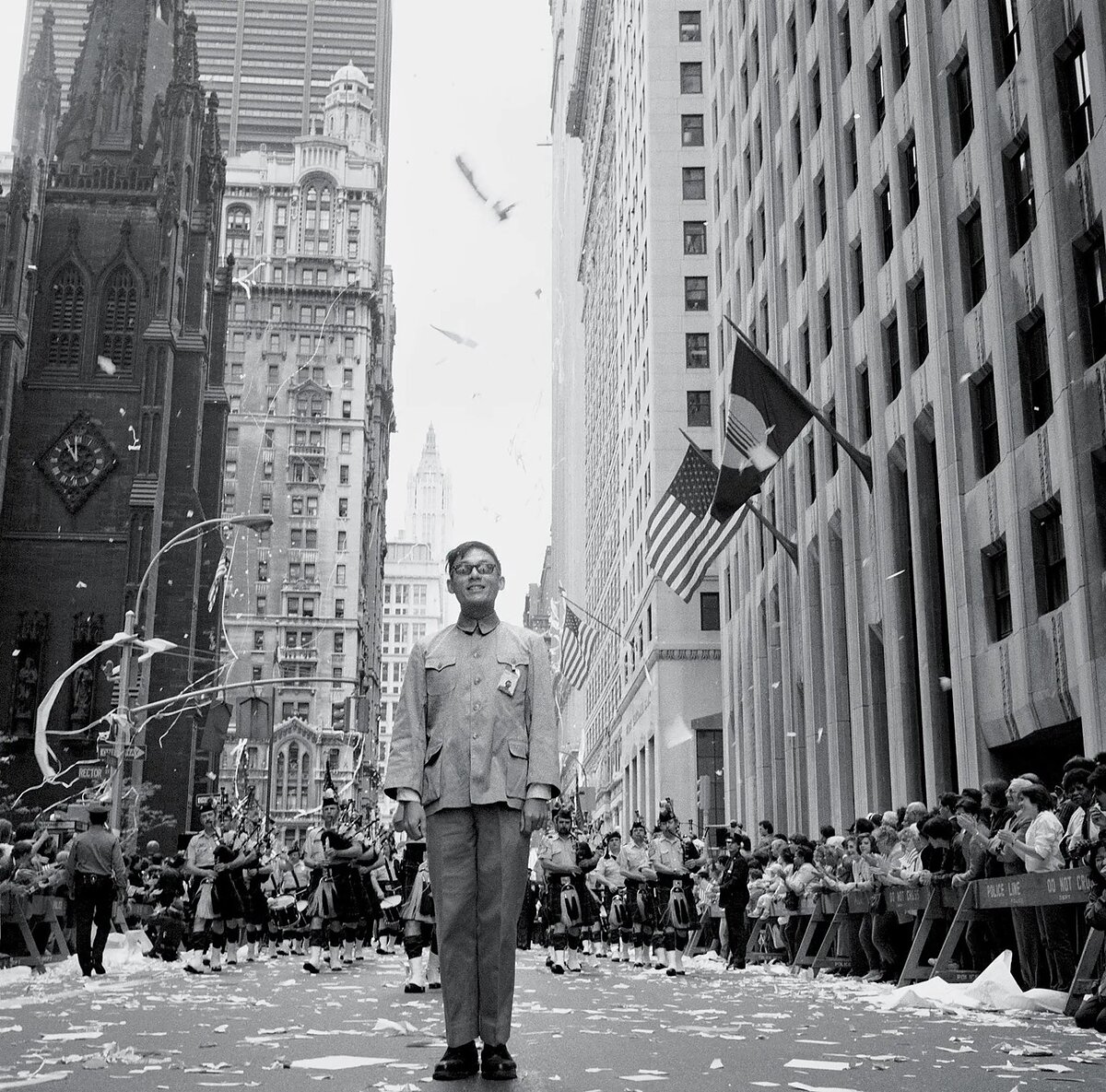

By that period, the artist Tseng Kwong Chi had created the bulk of his 10-year series of highly public self-portraits taken at international landmarks, beginning in New York. Dressed in a Mao suit, Tseng presented as a kind of emissary, visibly out of place yet, as exemplified by an isolated portrait amid a crowded Veterans Day Parade in Manhattan, still invisible. His poses echo the stance of an indelible 1985 portrait by Hanh Thi Pham, in which the artist, shown waist up, wearing a crisp áo dài–like shirt, and holding a pipe, seems to anticipate and rebuke any assumption that might accompany the gaze that meets her inscrutable, piercing one. In a nearby photo by Simon Leung, a pose alone carries racial connotations. The image of him squatting nonchalantly in Vienna considers how instincts translate and shift across geographies. To closely examine the work, hung low, viewers are compelled to squat too.

Rich in portraiture, “Legacies” also features works in which the racialized (and gendered) body isn’t explicit, suggesting varying modes of opacity or the search for something beyond the limits of representational politics. Byron Kim’s 1994 Belly Painting (Blue/Green) of a protruding, isolated lump and Tishan Hsu’s ambiguous aperture in monochrome pastel are studies in abstraction both alien and familiar. Artists such as Yong Soon Min, Carrie Yamaoka, and David Diao use text to feel out the capaciousness of language, with works that focus on words like why and where, slaughter, history, and imperiled revealing and reframing malignant narratives.

“I began searching for a history, my own history, because I had known all along that the stories I heard were not true and parts had been left out.” This desire for wholeness, expressed by Tajiri in History and Memory, echoes in the abundance of “Legacies.” Like the video, the exhibition collages varying voices into a pointedly unresolved record. What it accomplishes is a kind of memory work, providing a historical, complicated scaffolding for the many exhibitions in recent years grouping together Asian Americans—examples include “Scratching at the Moon,” “8 Americans,” and “Wonder Women”—as well as forebears to present-day practices. The ethos of the legendary Bernadette Corporation, whose fashion shows loop on video, resides in the collective CFGNY; Basement Workshop built bonds from which emerged the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA).

As it looks to the past, “Legacies” also provokes looking forward to ask what legacies Asian Americans are building today. It comes at a time when MOCA faces weekly protests led by Chinatown youth for what organizers view as the institution’s complicity in displacement and mass incarceration. When the Noguchi Museum—whose founder demonstrated a singular kind of solidarity with Japanese families at the Poston incarceration camp—has implemented a ban on its staff wearing what it refers to as “political attire” (but has been enacted specifically in reaction to the keffiyeh, a Palestinian symbol of liberation from settler colonialism). And when US voters are considering electing their first Asian American president, a South Asian and Black woman who touts her familial legacies while she effectively pledges to end those of countless in the Middle East, from Palestine to Lebanon. Representation can bring an illusion of change. We lift that veil by recognizing the abundant contradictions within shared experience.

—Claire Voon is a writer and editor based in Brooklyn.