CFGNY on Using Fashion to Expand Asian Identity

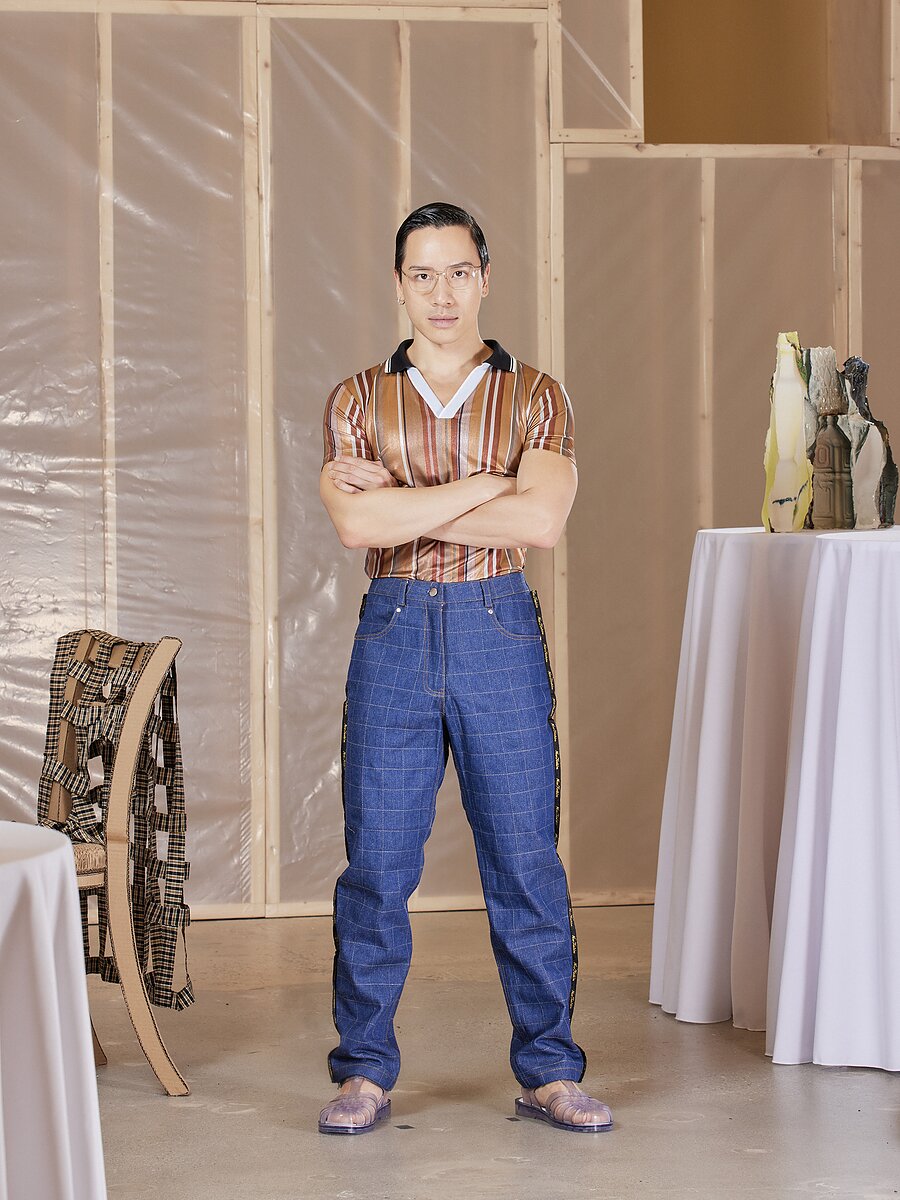

Depending on when and who you ask, the fashion label-cum-art collective CFGNY can stand for either “Concept Foreign Garments New York” or “Cute Fucking Gay New York.” These interchangable definitions both summarize the group perfectly in their own way, one in meaning and one spirit, and together are demonstrative of a deep-seated dedication to the pluralistic and plastic. Established in 2016 by artists Tin Nguyen and Daniel Chew, and recently joined by Kirsten Kilponen and Ten Izu, CFGNY uses fashion as a method and medium by which to tease out and blur concrete definitions of identity, race, and sexuality.

They have exhibited their collections at institutions and galleries around the world, including Beijing’s X Museum, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Berlinische Galerie in Berlin, and 47 Canal, and have become a burgeoning cultural force, bringing together constellations of their “vaguely Asian” community and questioning how we define Asian-ness.

This past January, as part of their current exhibition at Japan Society, CFGNY presented their fourth runway show, titled “Fashion Max 2.” Moving to the grating rhythms of Okkyung Lee’s cello score, CFGNY’s cast of models were a dynamic embodiment of today’s Asian creative universe. Among them were artists like Korakrit Arunanondchai, Diane Severin Nguyễn, Paul Pfeiffer, and Josh Kline, the musician Miho Hatori, chef Chinchakriya Un, and cultural movers like Patia Borja, West Dakota, Blake Abbie, and Nick Anderson. The 35 models flowed through every corner of the museum’s at-capacity atrium wearing bulbous, plushy-stuffed mesh skirts; gleaming faux snakeskin jackets; jelly sandals; mesh; patches; vinyl.

Following their electrifying presentation, CFGNY’s Daniel Chew and Ten Izu sat down (virtually) with the Amp’s editor, Shannon Lee, to discuss the making of their show and what it means to be “vaguely Asian.”

DC: Me and Tin first started working together in 2016. We were going to a lot of sample sales together and we would just nerd out about fashion. At the time, we didn’t name it, but it felt like there was this vaguely Asian thing of being at sample sales, being cheap, and getting designer clothes. In talking about that sensibility, Tin mentioned how growing up, his mom would travel to Vietnam and get clothes made for him. There’s a huge tailor industry there set up specifically for tourists and expats where they can make suits in a day; it happens in Hong Kong too.

At that time, we both wanted to spend more time in Asia so we decided to do a project together using clothing. We taught ourselves to sew; we weren’t great at it but that was kind of the point. For our first show, we made really terrible prototypes that were pretty unfinished and raw and gave them to the tailors to refine.

What was interesting about working with these tailors was that they are so used to making clothes for Westerners and they had a very specific idea of what Western taste was. Because they saw us as Westerners and because they had to make a lot of decisions on how to construct these clothes, we always got items back with different designs and shapes; a specific kind of collar or a flare in the sleeves.

When we would ask them about their decisions, they would just say, “this is what Westerners like.” This became the typical communication that existed between us which was a kind of beautiful mistranslation. Those sorts of details were always incorporated into the clothes.

From the beginning, it was always about modes of difference that happen in a diasporic experience. That sat beside this idea of going back to trace our “authentic heritage” or cultural legacy; this idea that I’m the authentic carrier of this tradition into America or something. Our project was always about this tension of being Asian but also not at the same time. It explored the different perceptions we had of the tailors and the ones they had of us and how that’s translated through the clothes.

DC: I think their perception of the west has changed a lot through their interactions with us. We’ve worked with some of these tailors for years now and they’ve kind of come to know the CFGNY style. For our RISD Museum we did in collaboration with Triple Canopy, we asked the tailors to design a CFGNY look based on having worked with us. It was a way for us to try to open up a conversation around a diaspora identity with them.

Their framework for thinking about these things is so different; they don’t think about racialization in that way because they’re not diasporic. It became this meta-critique of us, how in trying to bring our work to this other place, it highlighted just how American we are. Like, they wouldn’t describe themselves as Asian.

DC: Yes. In inviting us, Tiffany was really trying to open up what Japanese-ness could mean. How does a diasporic conversation about Asian-ness affect Japanese-ness in America? And how has Japan influenced America’s perceptions of being Asian due to its enormous cultural footprint in the ‘80s and '90s?

The Japan Society team has been so helpful in putting our exhibition together. The show itself was us going into the Japan Society’s archives and making work in relation to it; it being this American organization founded by American businessmen a long, long time ago…

TI: Our starting place was these speed Taobao modeling videos. Specifically, this one famous older woman doing all of these glitchy gestures that are also really studied, smooth, and controlled. This phrase kept floating around—"possessed by e-commerce.“ We were interested in having some of the models enact that possession.

We were also thinking about the way that we had produced this collection. Only Tin went to Vietnam over the summer and we were all on this insane text chain. Because of the time difference, Tin would go to the markets at 10am, take a million photos of fabrics, and then be like, "choose them!” and he would go to sleep. Then we would wake up, give feedback, then we would go to sleep. He was also using WhatsApp to keep track of and communicate with all of the tailors.

In that aspect, the internet was a very important part of our thinking about this collection.

TI: We were interested in using Japan Society as its own prop; it’s our source material for our whole exhibition. There’s this crossover of corporate symbols and intense cultural cultivation with objects like the [George] Nakashima benches… there are actually offices at Japan Society that are furnished solely with Nakashima furniture. We also saw folders and folders in the archives of interior decorating receipts and they’re so specific about all the details. But they let us build a whole bridge through their water feature!

But going back to Sigrid’s choreography, I was amazed at how she was able to get 35 models in order within such a short time period. She has a really amazing presence and ability to direct people, even if they’re not models or performers. She’s able to make people who don’t necessarily work with their bodies feel comfortable.