Li Jun Li and Yao on Representing Asian Americans in the South in “Sinners”

Watching director Ryan Coogler’s vampire thriller, Sinners, I was struck by something I had never seen on-screen before: a depiction of the Chinese American community in the 1930s Mississippi Delta.

“Mississippi … is a road comprising of three lines,” Coogler explained in a recent interview. “As long as you stayed in your lane and didn’t cross, whether it was Chinese crossing over to the white side or vice versa, things were okay.”

This is stunningly embodied when we first meet the Chow family—Grace (Li Jun Li), Bo (Yao), and their daughter, Lisa (Helena Hu)—who own two grocery stores on opposite sides of the street as a response to segregation. Coogler masterfully exemplifies this dichotomy—and Asian Americans’ role within it—in a long tracking shot sequence where Lisa travels from the shop that serves African Americans to the one across the street where her mother is serving white patrons. The camera’s attention is then passed on to Grace, who repeats the pilgrimage.

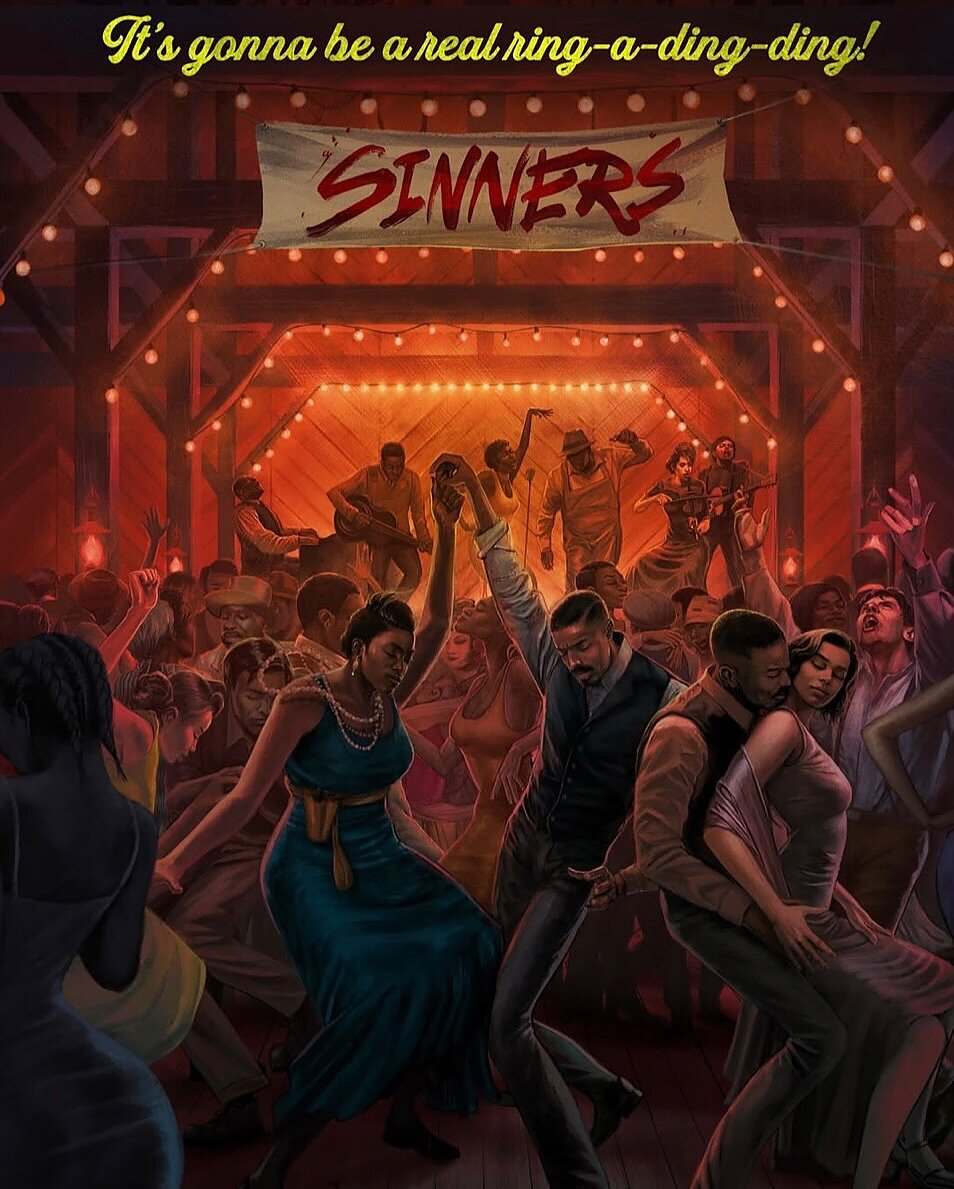

In the film, the family is helping a business endeavor of twin brothers Smoke and Stack (both played by Michael B. Jordan). Looking to open a thriving juke joint in an old saw mill, the brothers ask the Chows if they could donate food to the party and if Grace would paint their welcome sign. When Remmick (Jack O’Connell), an Irish-immigrant vampire, sets his sights upon the juke joint, the bonds of their personal and business relationships are tested.

For Li Jun Li, the role of Grace Chow was a unique one: she had not expected to ever be able to use a Southern accent in her acting career. It’s one of the many ways in which, with Sinners, Coogler creates space for Chinese Americans to tell their own stories and exist beyond the black and white binary, tapping documentarian Dolly Li as a cultural consultant after watching her documentary on the history of Chinese Americans in the region.

Ahead of the film’s release to HBO MAX on July 4, Li Jun Li and Yao spoke with us about collaborating with Coogler to highlight these lesser known stories in Asian American history, how Li’s work impacted their approach to their characters, and the joy of making Asians look sexy on-screen.

Major spoilers for Sinners follow.

Li Jun Li: Going into the scene, I was worried that people would walk away hating Grace for what she did. In the script, that scene before she makes that decision did not exist. The first time we see her and her daughter, Lisa, is in the beginning of the film and we don’t see Lisa again after. Based on that, it can be hard to empathize with Grace because we don’t revisit that visual again. Because the film has such a wonderful ensemble cast, you don’t get a full picture of what Grace was going through.

My notes were that before Grace opens the door, I need one more beat, moment, or short scene that captures the struggle of what she’s going through and the turning point in which she decides “This is where we’re at, we’re all dead anyway … I might as well go out there and make this sacrifice.” Ryan was so collaborative, receptive, and kind. He listened to my concerns and wrote in that scene which doesn’t happen very often.

LJL: It was great to have Dolly as a consultant. That documentary was visited repeatedly by Yao and I, especially when we were working on our accents. You’ll notice that Yao’s accent is slightly different from my accent, and that was based on the people that we spend most of our time with in the world of the film; for example, the store that Yao operates on is servicing a different population from the store that Grace is operating.

We were constantly asking questions when getting ready and in character. I was particularly curious as to whether the Chinese community wore their own traditional clothing—they were so deeply embedded in Southern culture so I wondered if that would manifest in their clothing. They would make Southern style Chinese food so that’s one way they would try to blend their culture with their surroundings.

LJL: I had a different idea of pace inside my mind initially. Ryan was the one who reminded me that when you see a best friend you don’t necessarily go “Hey, what’s up?” and then walk slowly to them. He was the one who introduced this idea of you go up, dap up, and then ask “What do you need?” Communicating that matter of factly underscores how deep their bond goes. The familiarity is such that the relationship resumed immediately after seeing each other.

Michael is such a chill guy and such a great teammate and leader that he immediately put me at ease. There was no need for me to be like, “Oh how do I build a relationship with him?” The relationship that you see on screen was built in between takes and just being as comfortable around each other as we are off camera, as we are on camera.

At the end of the day, we’re all just people. Afro-Asian solidarity existed back then as it did now, and to me, that’s not something I feel like I had to rehearse; I just wanted to convey the timeliness and timelessness of a friendship like Smoke and Bo’s.