Lotus L. Kang on Mirroring, Roots, and In-Betweenness

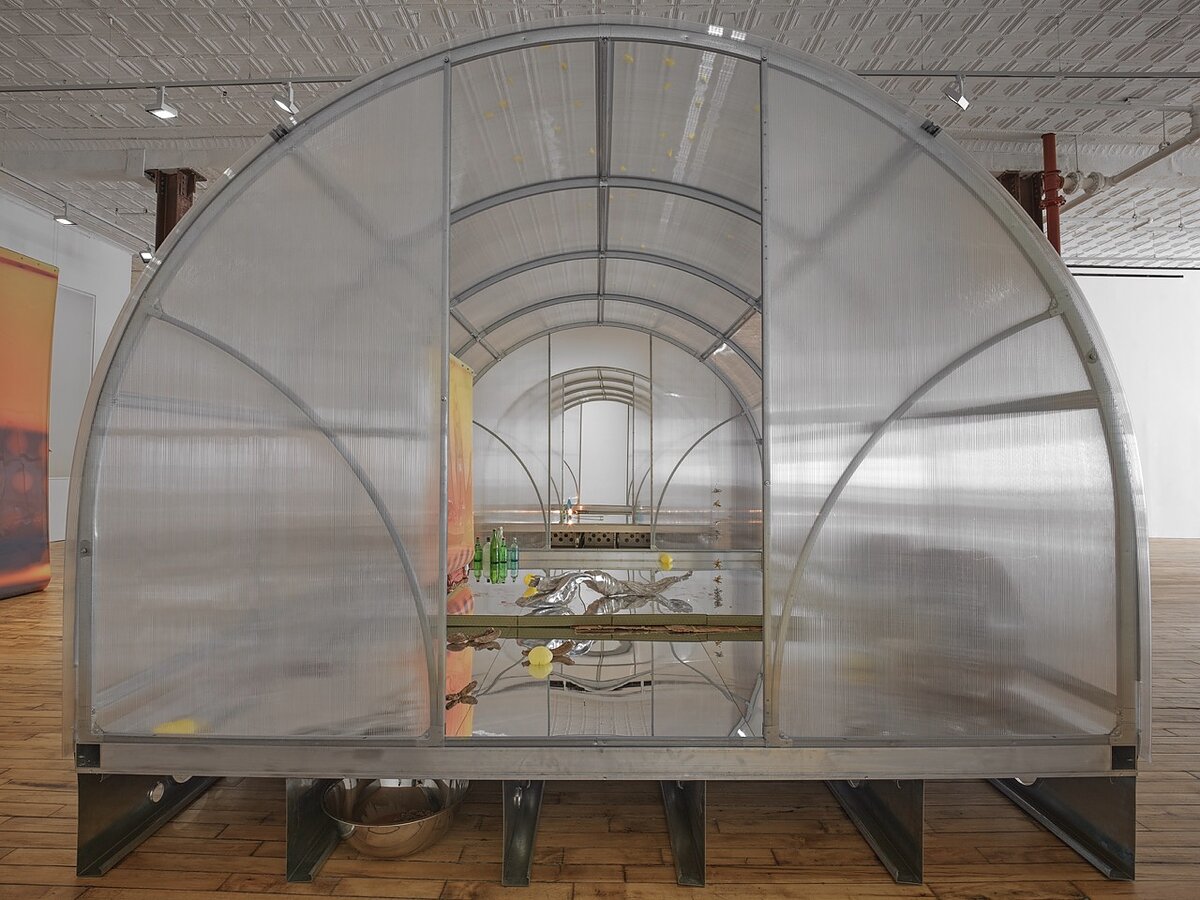

Positioned close to the ground, the semi-translucent greenhouses, photographic film, luminograms, collages, and kinetic sculptures featured in Lotus L. Kang’s current show, “Already” at 52 Walker communicate a sense of lowness that feels both sacred and profane.

The exhibition title draws from one of the 49 poems in Kim Hyesoon’s Autobiography of Death (2019), which explores the Buddhist tradition of after-death rituals performed in the 49 days between death and rebirth. The number repeats itself throughout the exhibition, with 49 objects in one of the greenhouses and 49-second intervals in Azaleas II.

For Kang, these works might be suggestive of religious icons, meant not just to depict, but hold a kind of transference, as in prayer or communication devices. For instance, in one of the greenhouses, a floor-based light bulb spins clockwise in the trajectory of a clock. Its glowing red light conjures a ritualistic stillness and warmth.

Following the cardinal points on a compass, the slow-moving bulb creates a sense of anticipation as it nearly touches a glass bottle but never quite makes contact, two bodies and spirits, so close yet forever apart—like Félix González-Torres’ Perfect Lovers (1987-1990) or Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (1508-1512). This intangible adoration echoes the diasporic experience: a closeness that remains just out of reach, an unattainable longing that crystallizes into Kang’s concept of “intimacy via distance.”

I first encountered Lotus L. Kang work at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto where I saw Mother (2019-ongoing). Silver bowls filled with pigmented silicone and cast aluminum replicas of fruits and vegetables evoked themes of metabolization and decay. I later saw Receiver Transmitter (Butterfly) in GTA24 at MOCA Toronto, where I was introduced to Kang’s signature greenhouse structure. Most recently, I experienced In Cascades (2024) at the Whitney Biennial in New York, an installation of light-sensitive photographic film suspended from the ceiling, capturing time through its shifting surfaces. Throughout these experiences, I was deeply moved by the way her site-responsive installations evolve in relation to the viewer’s movement through space, offering a poetic meditation on duration, rhythm, and transformation.

On view through June 7, 2025, “Already” marks the Toronto-born and Brooklyn-based artist’s solo exhibition with 52 Walker. I spoke to Kang at the gallery about her approach in this exhibition and the recurring themes of mirroring, reflection, body, roots, and in-betweenness.

LLK: Baby rats have this capacity to provoke very dualistic emotions, particularly one of care and tenderness and one of total repulsion and destruction. The baby birds came through reading a lot of poetry with bird imagery.. I had also been thinking about mother bodies for a long time, whether it be a biological gendered mother, or other kinds of mother figures that constitute a body in terms of time, inheritance, histories, and cultural entanglements.

I don’t fully recall but I might have initially come across an image of a baby bird, and I was struck by its open mouth and deep desperation. It looks up and out at the world from a horizontal nest. I was interested in the baby bird as a kind of new life that is extremely vulnerable, unable to fend for itself; in that sense to me, it is almost alive and dead at the same time. Of course, they also speak to ideas of care, inheritance, and passing along. Baby birds ingest regurgitated food from their parents and metabolize it again, so it is going back to this idea of my work as a regurgitation. It is a translation that becomes another translation.

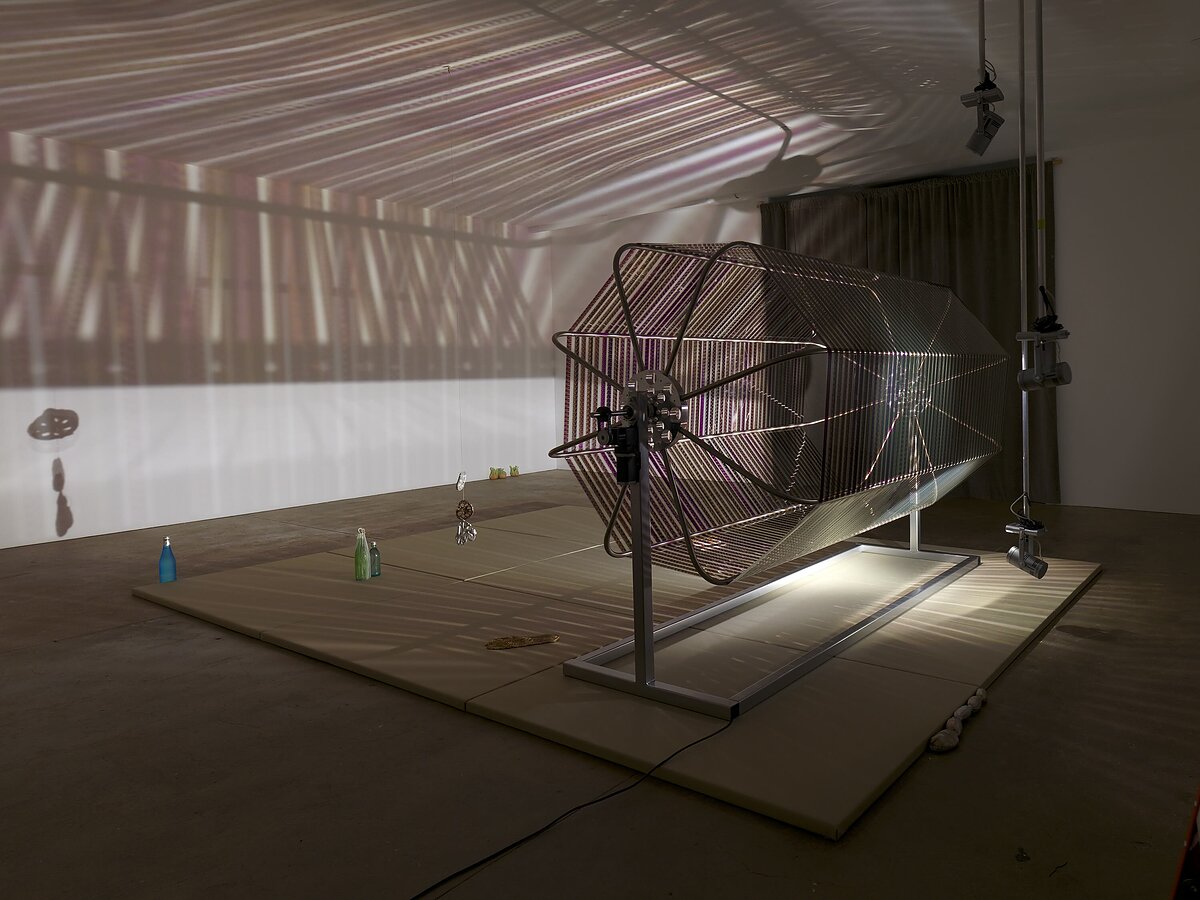

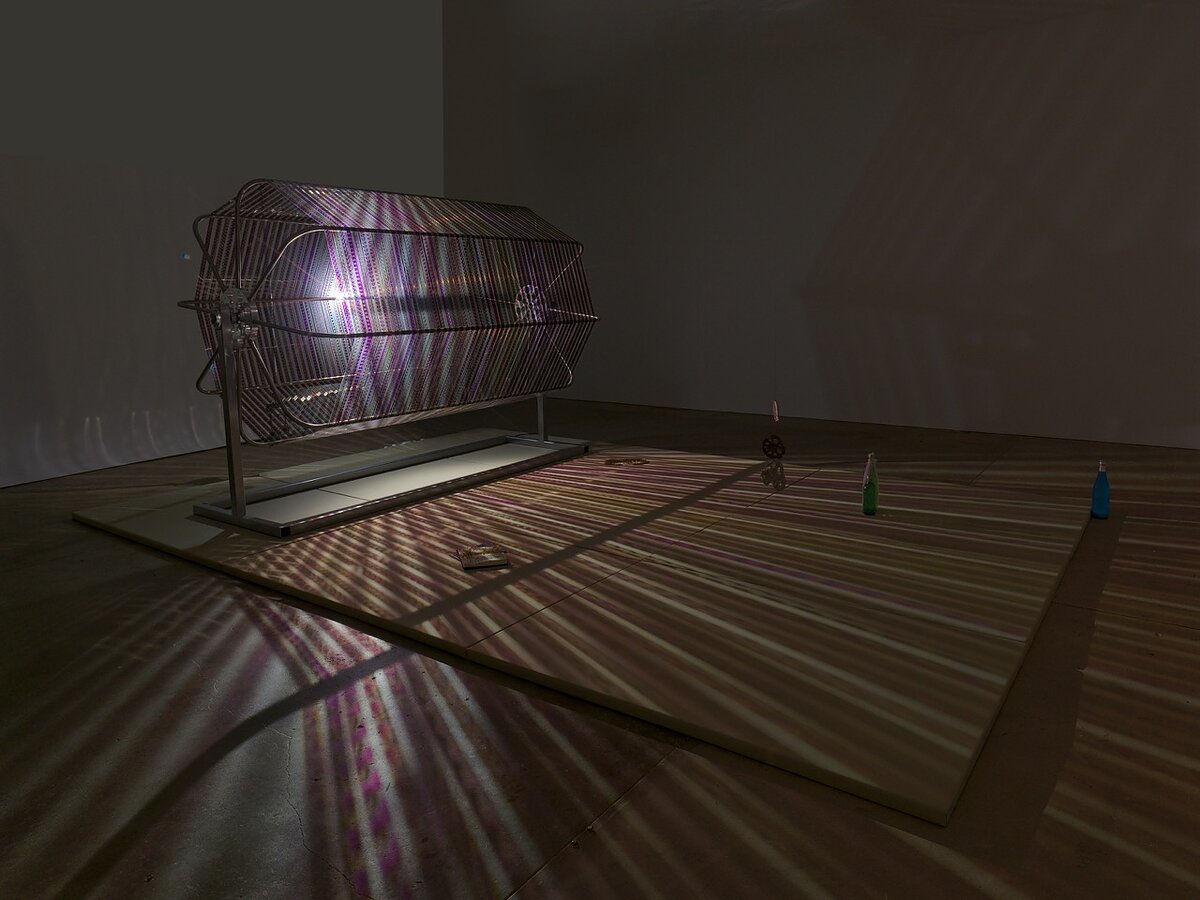

LLK: Yes, it changes speed. This work was catalyzed when I enrolled in experimental filmmaking classes and came across this tool called a rotary film dryer. It’s a way to dry film, but it is also a very process-oriented form and I became obsessed with it and wanted to enlarge it and turn it into a site of projection. I was reading translations of modernist Korean poetry, and I came across multiple interpretations of the famous poem Azaleas by Kim Sowol, which was written in 1925, at the time of Japan’s colonization of Korea. It’s an almost saccharine poem that describes a woman losing her lover. She spreads azalea flowers in her lover’s path and resolutely says, “I won’t shed a tear as you turn around and leave me.” It’s full of loss, longing, and sorrow, but it has also been interpreted as a metaphor for the loss of a nation. A poem inherently resists a singular meaning, and it changes over time and in relation to the body reading it; Azaleas was the first time I explicitly thought about undoing or translating this poem.

I filmed flowers. There are roses in the first iteration and now purple orchids with Azaleas II. They are never azaleas captured. There is always this gap or loss, a kind of break from the origin, which also describes this diasporic gap: you can never touch the origin, even though it’s of you.

The rotation pattern follows a score I wrote that combines one stanza of the poem Azaleas with one line of Kim Hyesoon’s poem, Already. The rotations follow the syllabic meter. Between series of rotations there are gaps of 49 seconds wherein the sculpture is moving very very slowly, and then there is also a 49 second period of stillness, then the whole score mirrors and repeats from there.

Then there’s the base that the sculpture rests on, holding a constellation of objects. One of them is Kim’s book Autobiography of Death, in Korean, opened to the poem Already, and then underneath it is a photograph I took of a mudflat I visited in South Korea. I’m doing research on mud and tidal flats, which are ecosystems which have a very in-between quality as well. And underneath it is a cast aluminum copy of the book In Praise of Shadows by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki.

“Lotus L. Kang: Already” is on through June 07, 2025 at 52 Walker.

—Gladys Lou is a writer and curator currently pursuing an M.A. at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College. She was awarded a Fulbright scholarship, where she studied Digital Arts and Experimental Media at the University of Washington in 2022.