Christine Sun Kim on Motherhood, Rage, and the Future

“The ghost of time has been here throughout. Her work engages multiple temporalities of transmission, apparatus, circuit, and reception.”

–Seth Kim-Cohen, “The Old Saw About the Tree,” in Christine Sun Kim: All Day All Night

Leaving Korea at a young age, I had, unbeknownst to myself, internalized a certain kind of loss. It was not only that I came to a country where English was the predominant language and I did not yet speak it—time seemed to have collapsed. I felt that I had become a baby, helpless and unable to communicate. Space was also altered; I missed Seoul and its landscape. But more than that, I missed the place where the mountain was called “산,” the road was called “길” or that the park was called “공원.”

I missed being able to understand a language, but I also missed its sounds. The murmurs of my parents talking in the living room when I was trying to eavesdrop on them while in my bedroom. I missed hearing those murmurs everywhere. I learned that language determined the way we moved our bodies; I learned how to tell from the articulation of someone’s back or head whether they are speaking in Korean.

Christine Sun Kim’s work has given shape to many of these nuanced experiences in language, sound, and bodies. Through drawings, installations, videos, and performances, the Korean American, Berlin-based artist offers a truer, more complicated understanding of communication—its methodology as well its ethics—, offering critical investigations into the politics of sound.

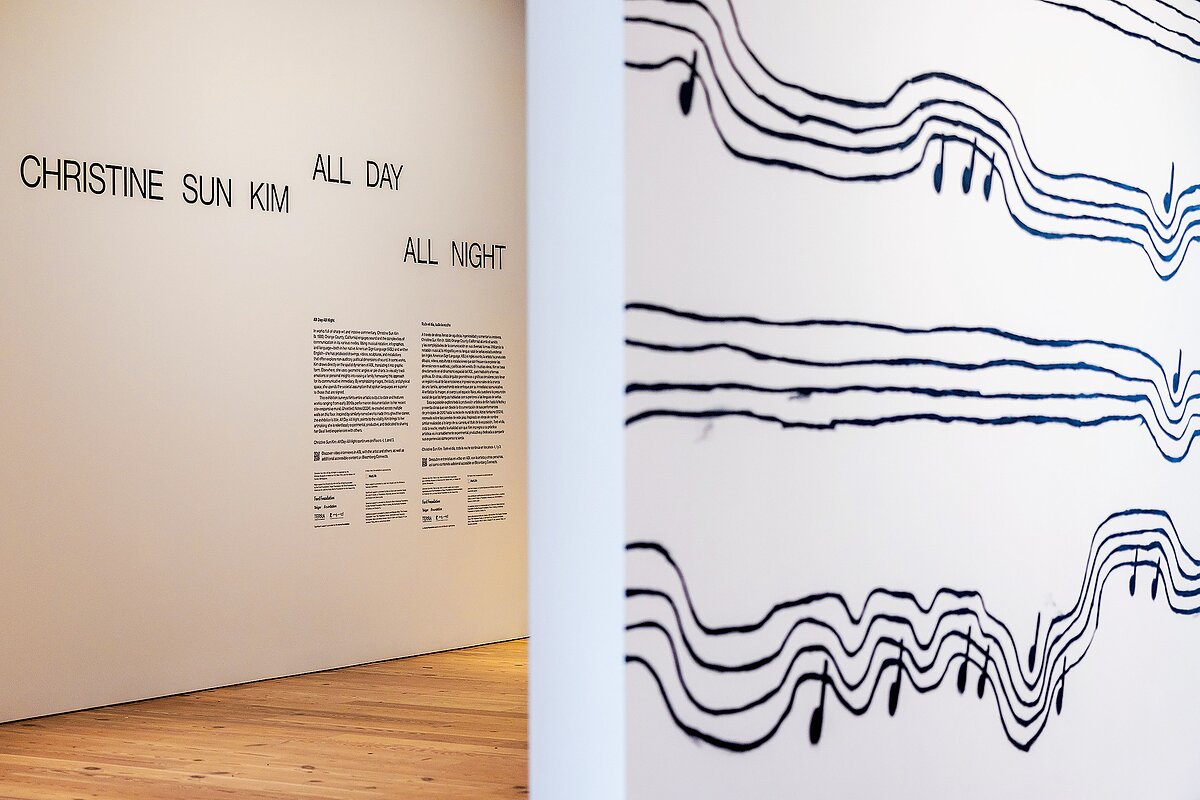

New York, February 8-July 6, 2025). Ghost(ed) Notes, (2024 (re-created 2025)). Photograph by David Tufino

Kim’s work has punctuated some of the most significant moments in my life. Kim and I first met virtually 12 years ago in 2013 (also a year of the snake) for an interview for ArtAsiaPacific on the occasion of her inclusion in MoMA’s “Soundings: A Contemporary Score” exhibition. Back then, she and I were both emerging in our fields, and she was beginning to gain notice for her performances and charcoal drawings; I was a young art writer trying to find my own voice and identify my instincts.

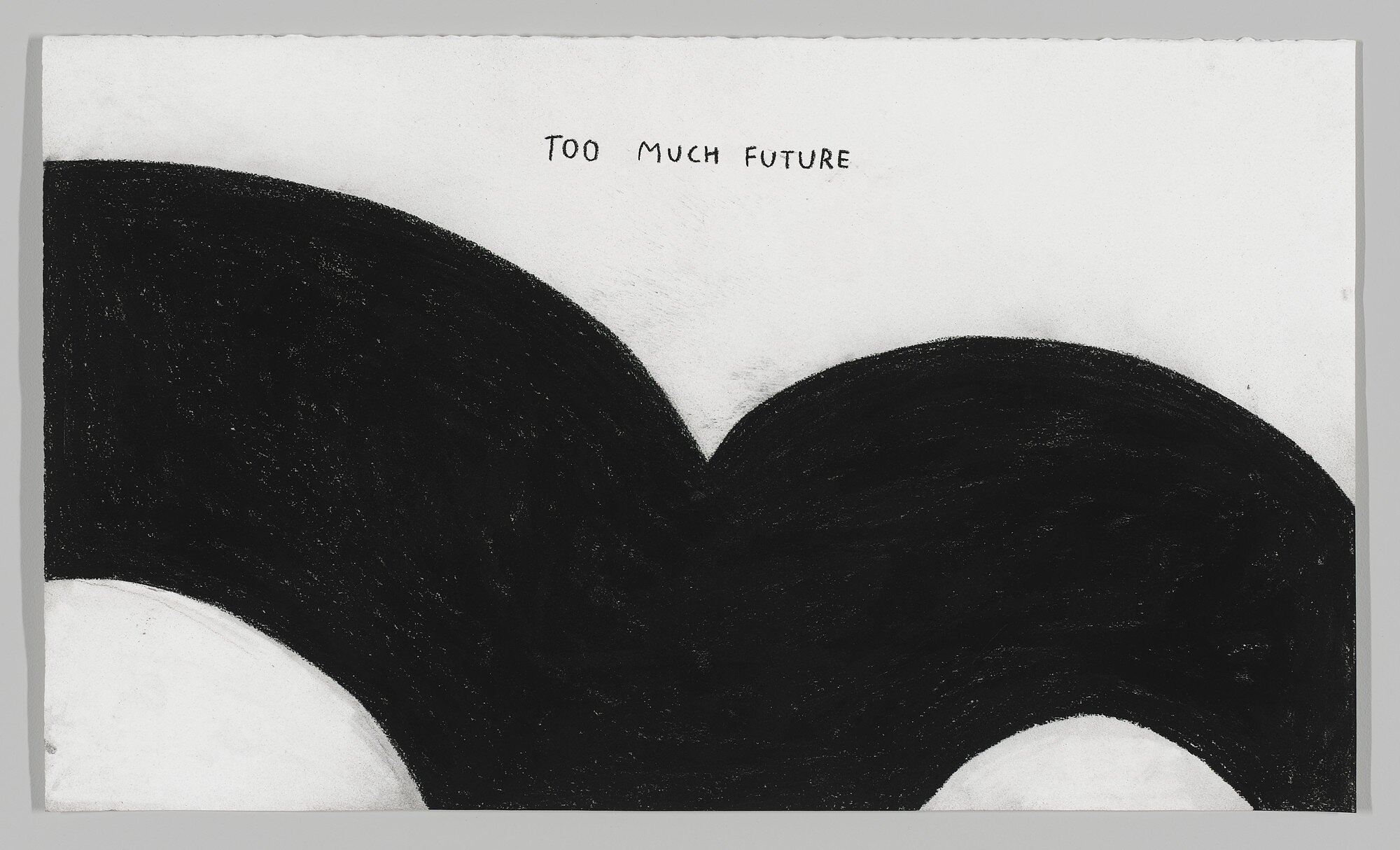

Five years later in 2018, I was pregnant and struggling with writing and life in so many ways. One lunch break from my day job, I walked down Manhattan’s High Line and saw Kim’s work for the Whitney billboard—two dark black arcs above which read the phrase, “Too Much Future.” The piece stopped me in my tracks and I cried. I thought about the future constantly when I was pregnant, deeply feeling that dialectic between the overwhelm vs. the possibility. I was so worried that I would not be able to live my life as a writer anymore, but also excited about having a child. Seeing this piece felt like a message of encouragement from my past, cast towards the future.

A full turn of the Lunar zodiac calendar since we first met, Kim and I finally got together in person on the occasion of her current survey at the Whitney Museum, “All Day All Night.” On through July 6, 2025, the mid-career survey chronicles Kim’s early sound performances, infographic drawings, videos, and collaborations with her partner Thomas Mader, providing an overview of the depth and breadth of Kim’s practice.

In a conference room at the Whitney, we discussed the trajectory of Kim’s practice, motherhood, and her Korean American identity, alongside an ASL interpreter.

New York, February 8-July 6, 2025). Mural: Prolonged Echo, (2023). From left to right: Long

Echo, (2022); Long Echo, (2022). Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Christine Sun Kim: It’s funny because you were saying how we met in 2013 and how five years later, in 2018, you encountered this piece. In some ways, Too Much Future represents a kind of halfway point. I also became a mom in 2017 and made the “Future Base” series that’s on the current exhibition’s eighth floor.

At that time, Jennie Goldstein, the curator here at the Whitney, asked if I wanted to do a billboard. At that point, I’d never shown anything at that scale; I wasn’t sure if my work had scalability. I didn’t know if I could take a drawing and scale it up to the size of a billboard. I’ve always worked with paper; I never thought about my work out in the wild. And having just become a mother, I was really overwhelmed.

The drawing for Too Much Future consists of two semi-circles—it’s just a line, a bounce, a line. I wanted to create space for feelings, anxiety, optimism, and anger, so I thickened the line. Where the billboard is located can either be the beginning or the end of the High Line; future or past.

It’s funny that this one simple billboard had such a big impact on my practice. That billboard ended up being a huge step in my career, allowing me to experiment more with scale. For Freedoms reached out not long after for a billboard commission. It brought me to adding murals to my practice.

It was also the first time I had an exhibition with the Whitney and Jennie Goldstein. In 2019, I was asked to be a part of the Biennial. And here we are today, working with Jennie again along with Pavel S. Pyś from the Walker Art Center, and Tom Finkelpearl as the three co-curators of this exhibition.

DSH: I was researching; I may have been on the Bard MFA site. Upon seeing your work I thought, I have to talk to this person.

It’s so nice to hear you discuss scalability with regard to your future series and I’m moved to hear that the work was just as pivotal to you as it was for me. I remember feeling so amazed and in awe that your work could be this big and this public.

CSK: I think it looks damn good [laughs]. It looks damn good, maybe in any size. I will also say that it’s nice to see it back in the series.

Truthfully speaking, it’s hard for me to be around my older works. Some of the things I made in the past I wish I had erased—but the curators weren’t having it. I have to show those older pieces. It took me a while to come to terms with that decision and accept it.

The “Future Base” series came about when Trump was first running for presidency. Those same feelings are even more relevant now. This show’s installation began the day after Trump’s most recent inauguration. The opening was the same day USAID funding was cut and some of the anti-trans bills were coming out. The White House website shifted into this militaristic theme with a video that’s like, “if you’re not patriotic, you’re not American.” They cut funding for Fulbright scholarships for Americans overseas.

Obviously, this administration is so against access. I don’t understand how deaf people voted their rights away. I don’t understand that at all. [A 2020 survey of disabled voters found that 51% of voters with disabilities supported President Donald Trump]. Accessibility used to be a bipartisan issue. And now, here we are in March. I feel like my exhibition is actually up at just the right time.

CSK: Hearing people can be “dumb” too. I was at a bar in New York with a bunch of deaf friends and this guy came over that we don’t know. We started writing to each other back-and-forth at the bar and he asked questions about our deafness and how we [my friends and I] communicate. He kept asking how we all get together and kept talking about how nice our clothes were. I’ve had similar experiences with journalists, asking me the dumbest questions. But I love those moments; I love when hearing people are also really dumb.

Educators and people who are in charge have always been hearing, and they have determined what’s best for me. They supposedly know better about myself than I would. I appreciate these moments where I’m out and meet people who are hearing and dumb; it helps me realize that I am normal. I’m not this thing people have to care and decide for.

Most of deaf people grow up with an inferiority complex, thinking that hearing people know best; that they’re in charge and they know all the answers. Then we hit a certain age, hopefully by adulthood, and we realize they’re fallible. They don’t know everything because no one knows everything. That’s not how the world works.

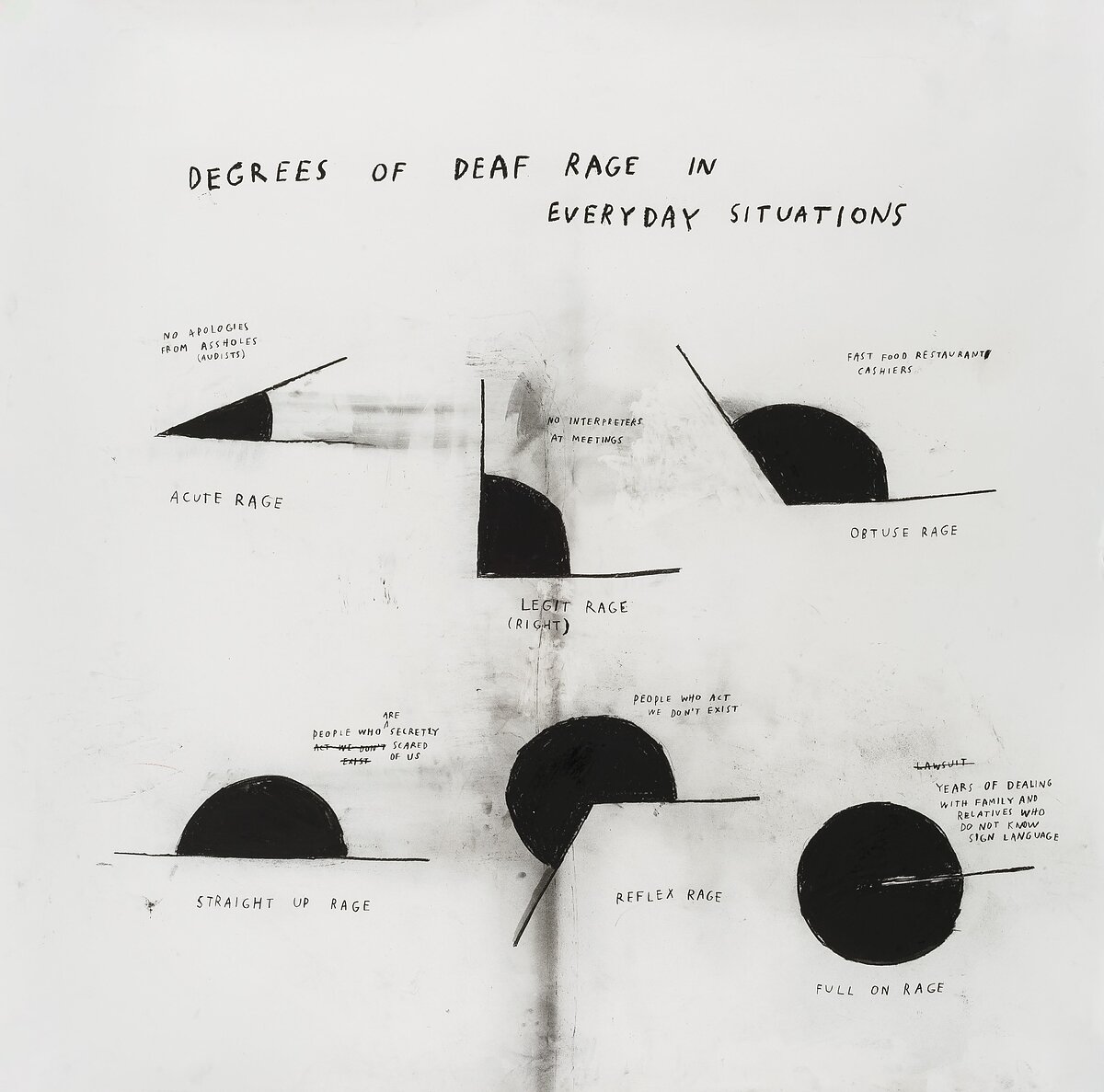

CSK: I make a lot of sketches that I work through. Some I keep, some I get rid of until I find the right infographics. With the pie charts, I felt like that was easy because they’re very instructional. Same thing with my “Degrees of Deaf Rage” series. I was like, “ooh, degrees…that will hold some rage.”

Usually, I start out with something quite small and then I might get into the size that I finally settle on. For the “Degrees of Deaf Rage” series, I had smaller sketches and then I scaled it up and stretched it out to the size that it is now. I knew I’d found the right size but I wasn’t finished with the amount of rage that I wanted to work through. I did another drawing for my Degrees of Deaf Rage in Everyday Situations (2018) and my Degrees of Institutional Deaf Rage (2018). I got to do a drawing on travel, education, and interpreters. And then I felt like, “okay, my rage is starting to wear out or diminish or run dry.” Finally, I did Degrees of My Deaf Rage in the Art World (2018). And that’s when I knew I was done.

People ask whether I immediately put my ideas to paper and whether that’s the final piece but I have so many notes that I work through. I’ll have iPad drawings, I’ll sketch it out, I’ll think about it, I’ll revisit those notes, I’ll revisit those iPad sketches, I’ll bring them into what I’m sketching through. I do that back-and-forth, back-and-forth. However, once I find the idea, once I’ve gotten the concept, I work very quickly to execute it all.

For me, it’s very hard to feel like there’s only one answer to a question. That’s shown in my practice as well. I have one idea, one question, and then I have all these answers. All these answers create the serialization.

CSK: Before I became a mom, I was so paranoid that by becoming a mom, I would be left behind or pushed away because I’ve seen that happen to others. What I realized instead is that things just kind of slowed down for a time and then resumed normal speed.

It doesn’t mean that it went away; it just slowed down for a little bit. I hate this idea of being a super mom—a mom who does everything by herself and can do it all. Right now, my mother-in-law is watching our two girls back in Berlin for three weeks. My sister has done that kind of thing, too. You can’t deny that these people who are important to you are helping. My community helps me. My family helps me. My partner helps me. I’m not doing it alone. It drives me crazy when people act like they are doing all these things alone when they’re not.

DSH: I loved seeing your work about [your daughter], Roux and the experience of family and being in love. I wasn’t expecting to feel or get that out of your show. It was imagining a way outside of this patriarchal construct and this narrow vision of parenting; it invigorated me about what motherhood could be like, if you embrace the collaborative.

One Week of Lullabies for Roux (2018) invites and opens up space for parenting to your friends, giving them a chance to care for your daughter in the form of a lullaby. Growing up, my dad used to tell us stories at night. He was the only one who did that except for his favorite brother and his favorite cousin. It’s a privilege to be able to tell someone, a child, a story at nighttime in order for them to then go to sleep. That’s very vulnerable. How did you select the seven people to participate in your lullabies?

CSK: I set up some criteria. Anyone I asked had to also be a parent. Some of these parent friends are very close friends of mine, some not as much. The lullabies had to be wordless and low frequency. I also asked participants to write descriptions of their lullaby. I didn’t ask anyone to check to make sure that they were good, that they were of a certain way. So this does play a lot around concepts of trust, which come up in collaboration.

The point of this piece wasn’t to create lullabies that would actually put Roux to sleep. It was more about the collaboration with other artist parents. When Roux was first born, we had this baby monitor that would notify me when Roux woke up using flashing lights. To soothe her back to sleep, the baby monitor had buttons that would play a random preset lullaby; I thought, why would I engage with these random lullabies that I don’t know or care about? That was the initial inspiration for the artwork.

CSK: Growing up, I was too busy polarizing my deaf identity and trying to find out how to be better at it. To me, the pursuit of my deaf identity feels similar to my experience with whiteness.

Oftentimes growing up, I didn’t feel deaf enough because I didn’t go to a deaf school, but I have a deaf sister. And then I have this identity of not being white on top of that. I had this inferiority complex that comes from being deaf in a hearing world.

With my family, we were Korean at home but the minute we stepped out of the door, I became deaf. There just wasn’t a lot of room for nuance or as much room for diversity growing up. Also, with some of the family issues that I’m having now, I feel far away from my upbringing. I’m in Germany. I’m an older parent.

When I go home to visit my mom and dad and my sister, we still have a lot of Korean practices that we do around bowing and food. But I also feel like my deaf identity was more of an identity for me. When I’ve engaged with my Korean extended family, I’ve actually lost some relationships with them because they didn’t learn to sign by a certain age. I can communicate with my parents and my sister, but I got old enough where I have my own family.

We have this dynamic around sign language and spoken languages. My daughters are half Korean and Germany is not a great place to be Korean, as there’s limited exposure to being Korean. If we were raising our kids in the coastal US, it would be great. But I found a Korean school. I found Korean friends. And I have a lot of Korean American friends now. I think especially losing some of my cousins, I’ve looked to reconnect with my Korean identity. And a lot of my Korean American friends are badasses. They’re designers. They’re actors. And I feel really moved to be in their presence and moved by our shared Korean-ness. And now I want to make sure that my kids do get that Korean identity. I don’t feel like I’m the best person to transmit it, though. Because I had “deaf” as an identity first.

I can say that I would love to do a year where I live in Seoul; I do feel that call. I used to feel so confused about all the different identities that I hold. And now I’m more clear on them. And because I’m more clear, I’m ready to expand them. So I feel good about my identity now.