“A Silence So Loud” Demands Careful Listening

What is silence? Is it just the absence of sound or the unwillingness to utter? The exhibition “A Silence So Loud” at Tiger Strikes Asteroid attends to the intricate impossibilities of “silence” in the face of historical trauma and emotional opacity. Co-curated by Tao Leigh Goffe and Cecile Chong, this exhibition interrogates the strained relationship between the living and the undying in the postcolonial—separation and intimacy folding into one another—while questioning the ways silence functions as a formal decision, an anomaly, a refutation, or a witness.

Credited by Goffe and Chong as the show’s inspiration, Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s 2023 film Because No One Living Will Listen sets the auditory tune for the exhibition. The two-channel video tells the story of a daughter searching for her father at the ruins of his memory. The narrative unfolds as the Vietnamese-Moroccan woman Habiba begins a letter to her Moroccan father in Vietnamese. Her father was one of many Moroccan soldiers who defected from the French colonial force during the first Indochina War and stayed in Vietnam.

Haunted by the “endless void” of her experience as a Moroccan-Vietnamese, Habiba is seen alone in the film, contemplating the removal of the graves that once occupied a misty green pasture on which she now stands, at a loss: there is no place she can go to pay tribute to her deceased father. There is no place for her to go. There is no place for her. There is no place. This historical non-place is rendered in cadence, shifting between scenes of mundane life cluttered with belongings, of a weathered woman mourning a childhood loss that disembarked a lifelong feeling of un-belonging. “It has been 60 years,” says Habiba. “I still don’t have a place to call home.”

The two frames shift in beat and alternating scale as Habiba advances on a path unknown, leading to the Moroccan Gate. Constructed by Moroccan soldiers in Thăng Long Citadel in Hà Nội (Hanoi) to mark the end of the war, the gate is shown in different scales in the film: at times monumental, in others miniaturized, and at once all-encompassing, fragmented, solid, and hallucinatory. Mapping the psychological topography of loss and destitution, Nguyen masterfully makes the effects of historical erasure on personal memory palpitate.

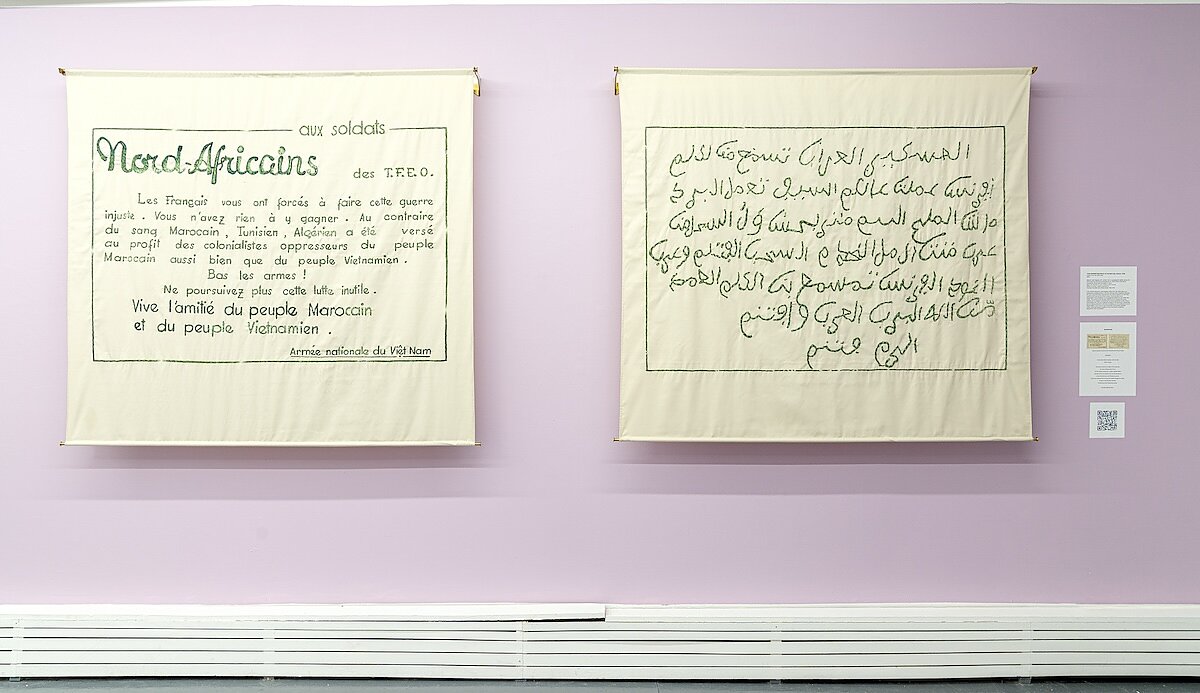

“Who is disinherited by the silences of overlapping wars of occupation in Indochina and North Africa? ” asks the work’s wall label. To the left is another work by Nguyen: two banners embroidered with parallel messages in French and Arabic hanging against a light purple wall. Translated from a propaganda leaflet from the 1940s and ‘50s, the text in Letters From the Other Side (2023) urges North African soldiers serving the French force to put down their arms against their oppressed brothers in their colonizer’s war: “Vive l’amitié du peuple Marocain et du peuple Vietnamien (Long live the friendship of the Moroccan and Vietnamese people).”

On the opposite wall is an arrangement of pages by the Singaporean artist Sim Chi Yin, Ah Ma (2024). The display chronicles Sim’s father’s journey in Europe through the postcards he sent to his mother, intercepted with letters to his daughter in Mandarin. This intergenerational storytelling interlaces family trauma precariously like a mystery, centering the unspoken foreground of the British Malaya War (1948-60), around which we learn about Sim’s missing communist grandfather in China, the toil it took on her grandmother in Malaysia, and the displacement of Sim’s father.

Elsewhere, artists Johann Diedrick and Jeremy Dennis contend with the formal manifestation of silence within postcolonial sensibilities and aesthetics. Diedrick’s Portal of the Collectors (2025) is made of two parts. The sound sculpture Sirens hangs from the ceiling with strings of wires interwoven with lightbulbs and small solar panels. On the floor, a conch shell rests atop an old radio circled with green and white fiber threads likely from a broken fishnet. With this bricolage of mediums, Diedrick references Caribbean sonic tradition at the intersection of nature and technology. When activated, the radio collects signals from distant shores in various loci of Black America, listening for incoming storms.

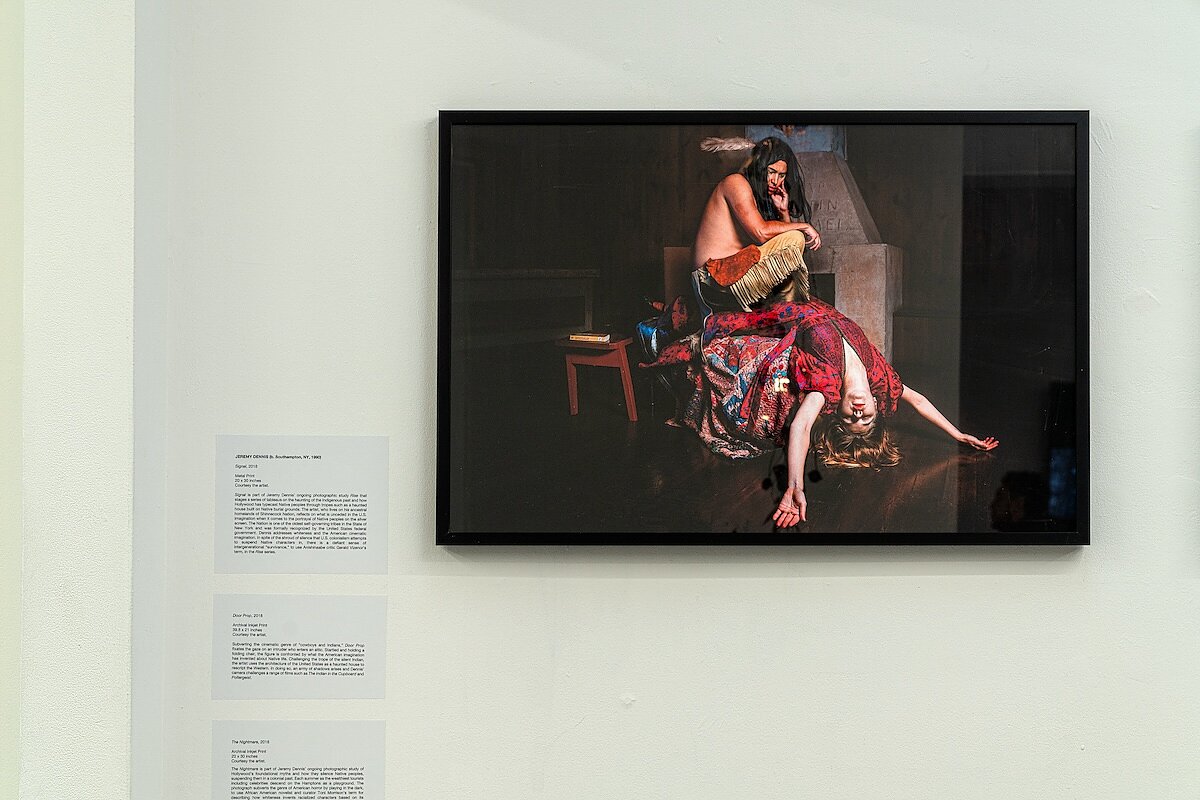

For Jeremy Dennis, silence appears as spectre; scenes of haunting pervade his work. The indistinct presence of Indigenous people in Dennis’s dark photographs trace a peculiar subversion, playing into the objectifying mystification of the Native American trope as the savage other. By staging the colonizer’s states of distress and fear in a theatrical center, Dennis’s work subverts the mystery back to its root. The result is a lingering sense of suspension—like weighted air under the memory of colonial violence, unacknowledged and illegible.

By departing from an affirmation of “silence”, this exhibition does not prod the colonial subject to speak, but rather challenges our attunement to subaltern eloquence. The artworks attest that the subaltern speaks despite archival erasure, epistemological occlusion, historical silencing—but have we learned to listen? In this way, the exhibition serves as a reparative beginning, demonstrating not only a discursive critique but also a guide to how we might truly listen, for solidarity and empathy.

“A Silence So Loud” is on view at Tiger Strikes Asteroid through April 13, 2025.

—Hindley Wang is a writer, curator from Shanghai, based in New York. She writes at the intersection of art history, pop and politics. Her writing is published in Frieze, e-flux, flashart, etc. She is also a part-time educator at the Cooper Union.