Interrogating the Foreignness of Language in “English”

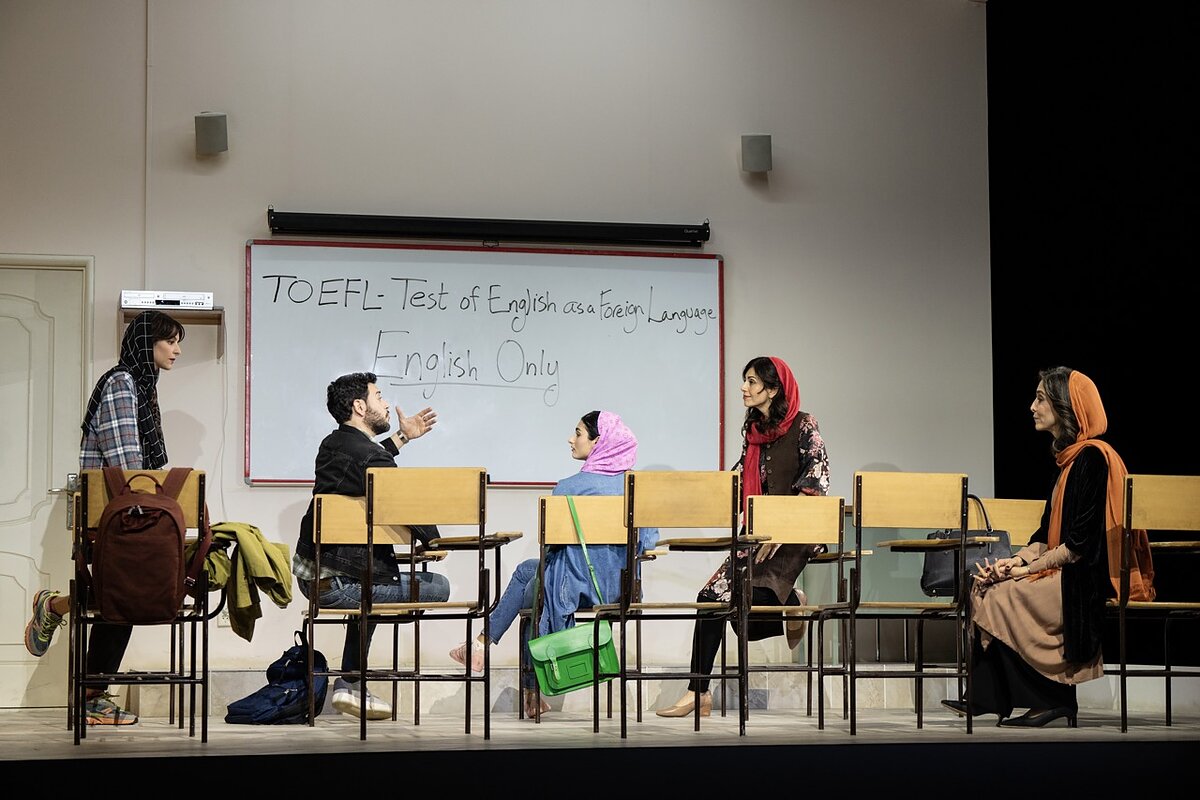

Set in the Iranian city of Karaj in 2008, English tells the story of an Iranian teacher and her four students preparing for the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). Written by Sanaz Toossi and presented by Roundabout Theatre Company at Todd Haimes Theater through March 2, the Pulitzer Prize-winning play solves the problem of communicating the nuances of a “foreign” language in an English-language production by using two distinct speech patterns.

In order to represent Farsi, the actors speak in a native, fluent English, allowing them to converse candidly and with comfort. This ease is in sharp contrast to the broken English they are learning that is drawn out and unsure of itself.

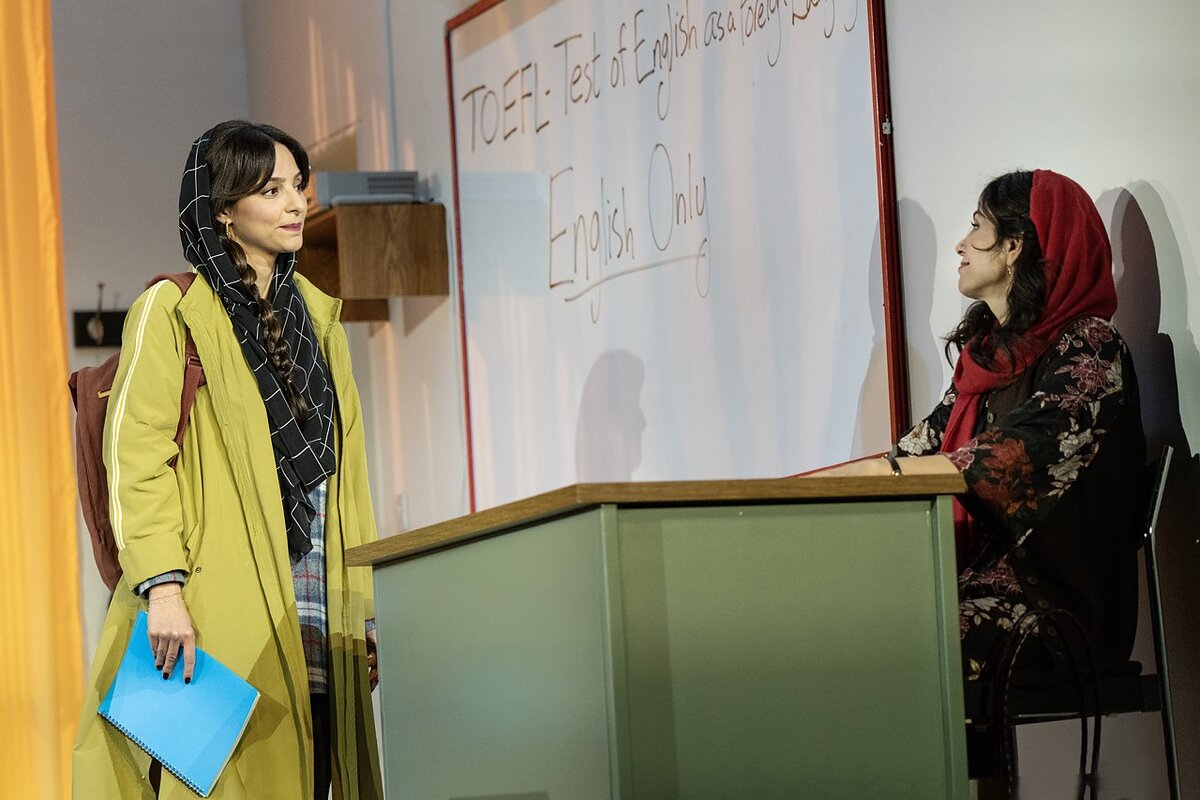

The production design is simple—director Knud Adams describes it as ”prismatic”—focusing on the single rotatic cubic set of a classroom and its balcony and window storefront. Anchored by the classroom’s teacher, Marjan (played by Marjan Neshat), the play volleys between her and her students, Goli (Ava Lalezarzadeh), Elham (Tala Ashe), Omid (Hadi Tabbal), and Roya (Pooya Mohseni), who throughout the play reveal and expound on their relationship to the English language and why they are learning it.

Goli muses that she enjoys learning English because, in contrast to Farsi, “English does not want to be poetry.” The youngest student in the classroom, Goli seems to love everything about the English language and western culture, reciting the lyrics to Ricky Martin’s “She Bangs” (“She bangs, she bangs—Oh baby!”) with comic reverence.

Roya is a grandmother studying English in order to visit and better communicate with her son and granddaughter living in Canada. “He wants her to be Canadian, I want to be her grandmother,” she says. As Roya tries to speak broken English and connect with her loved ones by reciting the characters from television shows like “Friends,” she will never be like them. Perhaps it is why we do not see her in the latter half of the performance.

While one might expect Persian music to be the backbone of the play’s score, it only appears once, through Roya’s playing Hayadeh’s “Soghati” during the class’s show and tell. The song also marks the first time we hear Farsi on stage; through it, Roya’s character is not only a mother but the vatan, the motherland.

Central to the play’s dramatic arc is Elham, a graduate student who struggles to translate herself and her intellect to English, manifesting in anger and embarrassment. English, for Elham, is an antagonist; she fantasizes about what it would be like if it were English-speakers that had to learn Farsi.

I related deeply to this experience. Months before I saw English, I helped my Palestinian cousin prepare to audition to be the understudy for Goli. Tasked with teaching her a Persian accent, I struggled to find a meaningful answer; all I could offer were a few stereotypes—the lack of a “w” sound, slow phrases weaving together with “eh,” and long pauses. As I read through the script with her, I couldn’t help but feel a tinge of embarrassment akin to when I would walk into a room of my mother’s friends and had to greet them in Farsi. As an Iranian American, I was taught both Farsi and English, but I learned embarrassment on my own. Embarrassment meant pronouncing simple pleasantries wrong, forgetting a word as simple as “purple,” or not connecting the vegetable I grew up loving was actually an eggplant in English. Like Elham, I found it hard to translate myself into both languages.

Meanwhile, the star pupil, Omid, is an enigma. Despite sitting in a TOEFL classroom in Karaj and his distinctly Iranian uniform of black loafers paired with skinny jeans, he somehow knows obscure words like “windbreaker” and often speaks English with greater ease than his instructor, correcting the way she pronounces her Ws.

Omid is a thorn in Elham’s side and a rose to Marjan. While Elham fights Marjan and the English language, Omid helps Marjan create that space between two worlds where her sacrifice was not wasted. Omid and Marjan only ever speak in English. Like the production itself, Marjan is tasked with representing two languages, two identities in one. Marjan’s character highlights the dichotomy of sacrifice—the sacrifice she made in the past to learn English and leave her home and her sacrifice to return to Iran and teach others English.

The only time Farsi is spoken between the characters in English is in its closing scene with a simple exchange of words between Marjan and Elham. The exchange isn’t subtitled, leaving only those who know Farsi with the key to the play’s conclusion. Through it, the actors stopped acting and became poetry. During a Q&A for the play, Toossi mentioned mixed audience reactions to the scene: some feel the ending is beautiful, while others demand subtitles. “If you can’t handle the discomfort of the last minutes, then you did not watch the play,” she rebuts.

In one of her last scenes, Roya objects strongly to having to choose an English name. “Our mothers get to name us,” she says with defiant sadness, “not foreigners.” Growing up, our mother’s terms of affection would translate to things like, “I would sacrifice myself for you.” English shares that intimate sacrifice boldly on stage as an ode to those who named us.

—Lili Emtiaz is an Iranian American Design Director and writer living in NYC. Outside of work they are an active volunteer on projects centered around art education and community revitalization.