In “BAR,” Artist Rujuta Rao Tends to the Entangled Histories of Feni

In her iterative “BAR” series, artist Rujuta Rao creates transitory environments that embody an inventiveness and curiosity that forms the core of her practice. The central premise of Rao’s bar involves introducing participants to feni—one of India’s oldest alcoholic spirits, hailing from Goa, which the artist serves alongside traditional snacks like salty banana chips, tart mango candies, and spicy murukku.

While sipping the fruity, spicy, and pungent beverage, participants explore Rao’s handmade books, which reveal the socio-political and cultural histories of feni alongside her personal connection to it. Experiencing the patchwork of histories, personal stories, and tactile objects scattered throughout the installation feels like piecing together clues to understand Rao’s interests and the speculative connections she makes. Just as with actual puzzles, solving these together is more rewarding, as all participants share in the experience.

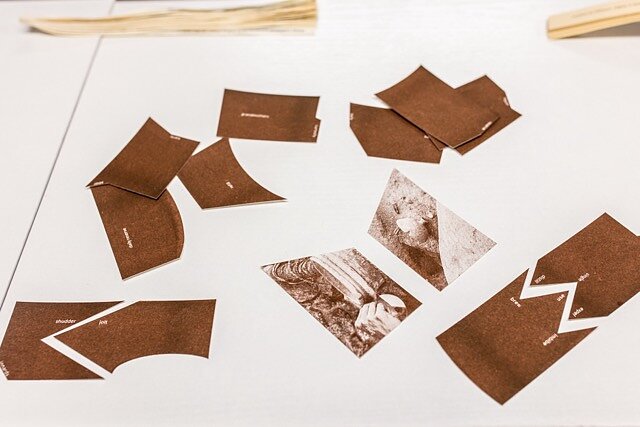

Feni itself, much like the artist’s relationship to it, is steeped in a history of migration and adaptation. The cashew trees used to produce the spirit were introduced to Goa by Portuguese colonizers in the 16th century. Though the Europeans discarded the cashew fruit, Goans—who had previously distilled the liquor from coconut sap—adapted their traditional knowledge to craft a new, more potent alcohol from the cashew fruit. In a book presented as a puzzle-like grid with movable paper slips, Rao reveals the meanings of distillation terms. As participants shift these slips, they learn about collmi, the trench where cashew fruits are squashed, and bhan, the pot used for distillation.

Another of Rao’s books in “BAR” tells a story of her family, who moved from Maharashtra to Goa and were considered outsiders despite their years of residence. In the book, which consists of long, narrow strips of bound paper with one sentence written on each, one learns about her grandfather’s small-scale production of feni on his farm. This act became a gesture toward connection to Goan culture, despite the enduring sense of being an outsider. The book’s narrative jumps between Portuguese colonizers, family memories, Goan landscapes, and Rao’s own first interaction with feni at the age of six. This method of fragmented storytelling mirrors the histories Rao explores—disjointed yet interconnected—as we’re made to flit back and forth between past and present, the personal and historical.

Each edition of Rujuta Rao’s “BAR” series introduces a unique constellation of books, objects, and table placements, and takes place in a new location each time, playfully embodying the spirit of malleability that lies at the heart of the project. This sense of fluidity is even reflected in the titles of each edition. The first installment, niro, and the second, soro, reference different stages of the fermentation process—niro being the first flush of cashew sap, and sorro the final, distilled product. This ongoing transformation echoes the evolving nature of the installation itself, where Rao continuously reconfigures elements to suit the context.

Rao’s books not only act as clues to these intimate and transnational connections created by the artist, but add to a social environment. Participants inevitably interact with each other, at ease in an environment that most are familiar with, creating different links of conversations, and puzzling through the tactile, interactive books together. The books also further speak to Rao’s interest in materiality and craft—traditions that affirm a rootedness in physical, tactile production even as it speaks to larger histories of movement and displacement.

The multiple levels of engagement brought out by Rao’s “BAR” recall the concept of relational aesthetics, a term developed by French art critic Nicolas Bourriard in the 1990s to describe works inspired by and based on human relations, where the audience is envisioned as a community and the artwork both produces and is produced by intersubjective encounters.

Twenty five years after the term was first introduced, we’ve seen escalating wars which started in the early naughts, a worsening climate, a global pandemic, and the complete erosion of the early internet’s optimism. In this context, marked both by alienation and hyperconnectivity, the simple act of coming together initiated by “BAR” feels radical; the ability to foster genuine dialogue and community can not be underestimated.

—Pallavi Surana is a writer and curator currently based in New York City.