David Henry Hwang in Conversation with Ping Chong

Lauded as one of the most significant multidisciplinary artists in the nation, theater artist Ping Chong announced his retirement from his position as Founder and Artistic Director of his company earlier this year. For nearly half a century, Chong’s genre-defying performances expanded the vocabulary of NYC’s avant-garde in order to better understand themes of otherness and identity. In his best-known series, “Undesirable Elements” for example, Chong explores how culture, identity, and politics become distilled into personal histories. By interviewing individuals within specific communities, Chong’s process is one that honors the profound and surreal poetics of the everyday.

His accolades include a National Medal of Arts, a Guggenheim fellowship, numerous National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, a Bessie Award for Outstanding Creative Achievement, and an OBIE Award for Sustained Achievement of Direction, among many, many others.

In celebration of his extraordinary career, Tony, Grammy, and three-time OBIE Award-winning playwright, librettist, screenwriter, and professor David Henry Hwang sat down with Chong to discuss his life, his approach to creating groundbreaking theater, advice for the current generation of artists in NYC, and what’s next after retirement.

PC: My parents immigrated separately and met in the U.S. They both arrived in the early 1930s in San Francisco at the turn of the century. There were something like five Chinese opera theaters out there at the time, seating up to 1,000 people. I mean, it’s really kind of amazing that they existed. But by the time they arrived, that scene was starting to diminish. That might have had something to do with the Great Depression. They ended up having to leave. I don’t know exactly whether it was because of immigration reasons, because I don’t even know how they stayed. But they had been in San Francisco for quite a long time. My sisters were born in San Francisco.

When they left, they wound up in Vancouver, which I think has the oldest Chinatown in North America. Eventually, they moved to Toronto. That’s where I was born. And then they came to the U.S. as part of a traveling theater company. That’s what it said on their visas. On mine, my occupation was listed as “infant.” I don’t know how they managed to stay here but when they moved to New York, they really couldn’t make a living supporting five kids from Chinese opera. My father also still had another wife in China, who had two kids who he continued to support.

Many of the Chinese opera people who found themselves in New York wound up in the restaurant business. Fortunately, we ate very well. And whenever any Chinese opera troupe came through town, we would always go and have good tickets and all that because we’re this old Chinese Cantonese opera family. But as a kid, I didn’t see western theater until I was in high school. I was seeing Chinese opera, Chinese movies, and western movies, of course, but my first western play was Julius Caesar in high school. So by that time, it was too late. I was not going to be heading in that direction. The roots are too deep, you know?

PC: I should correct myself. I didn’t start a company in ‘72. I did my first piece in '72. I didn’t officially become a nonprofit till '75. In 1970, I met Meredith. She was teaching at NYU and at the end of class, she came up to me and said, “You’re a good mover, come to my personal workshop.” And I didn’t go. I didn’t know what she was talking about; I’m a good mover? I had no idea what that meant. I had no history in dance at all. I studied film at film school.

Anyway, she invited me. I didn’t go but I happened to live in the same neighborhood that she lived in and ran into her. She said, “Why didn’t you come to my class? I have a class tonight. Come!” That day, I walked around the block four times to get up the courage to go take the class. And the rest is history. It’s because of Meredith that I’m here today. She invited me to join the company around 1971.

That was when I had my first performing experience, which was major because it wasn’t dance. It was more like performance theater. It was the wild days of the New York avant-garde. I was in a four-hour extravaganza with four different locations and over 80 people, horses, motorcycles, flares, bikers, a boat on a lake with performers painted red. I mean, it was wild. In a funny way, it wasn’t that far from my roots because it wasn’t realism. It was a highly stylized performance form. Almost immediately after I joined the company, I started doing my own work. My first piece, which I’ve revived and updated as the closing piece as Artistic Director of my company, originally cost $100 to make. This was New York when it was a much more artist friendly city. You could really survive on a nickel.

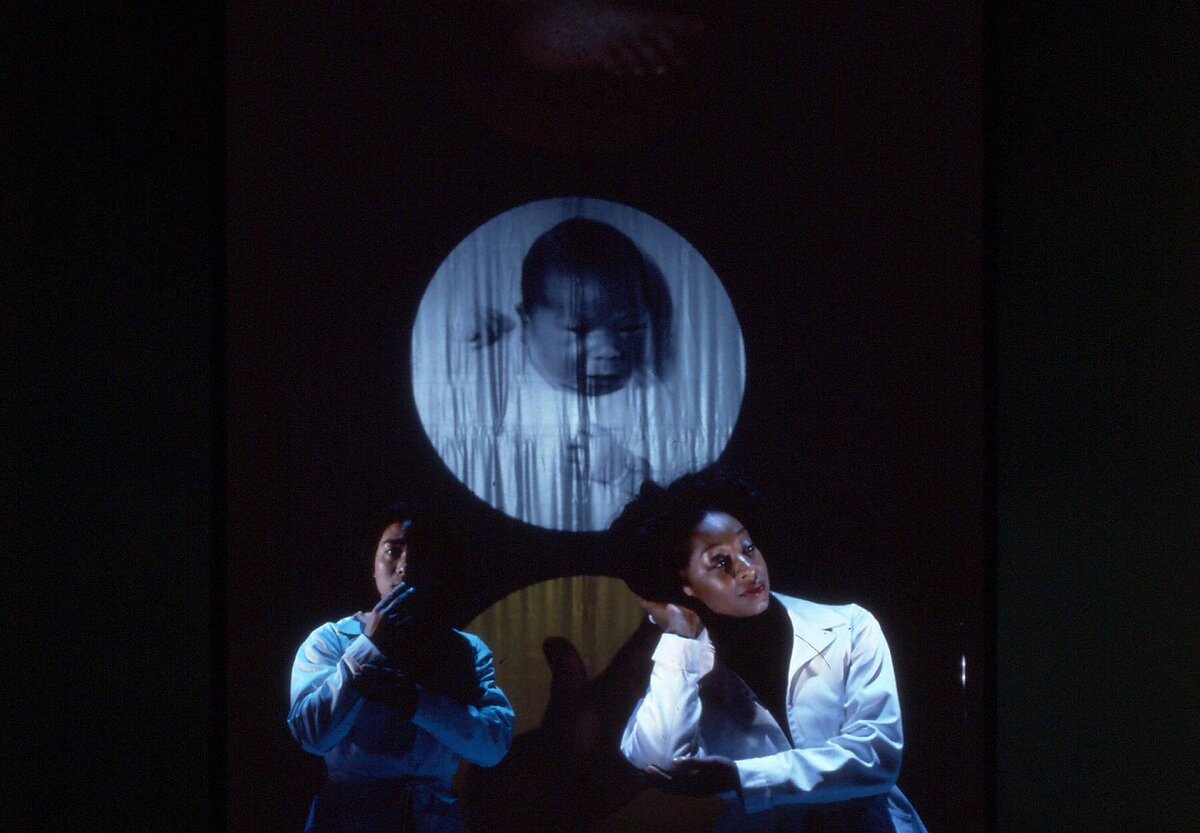

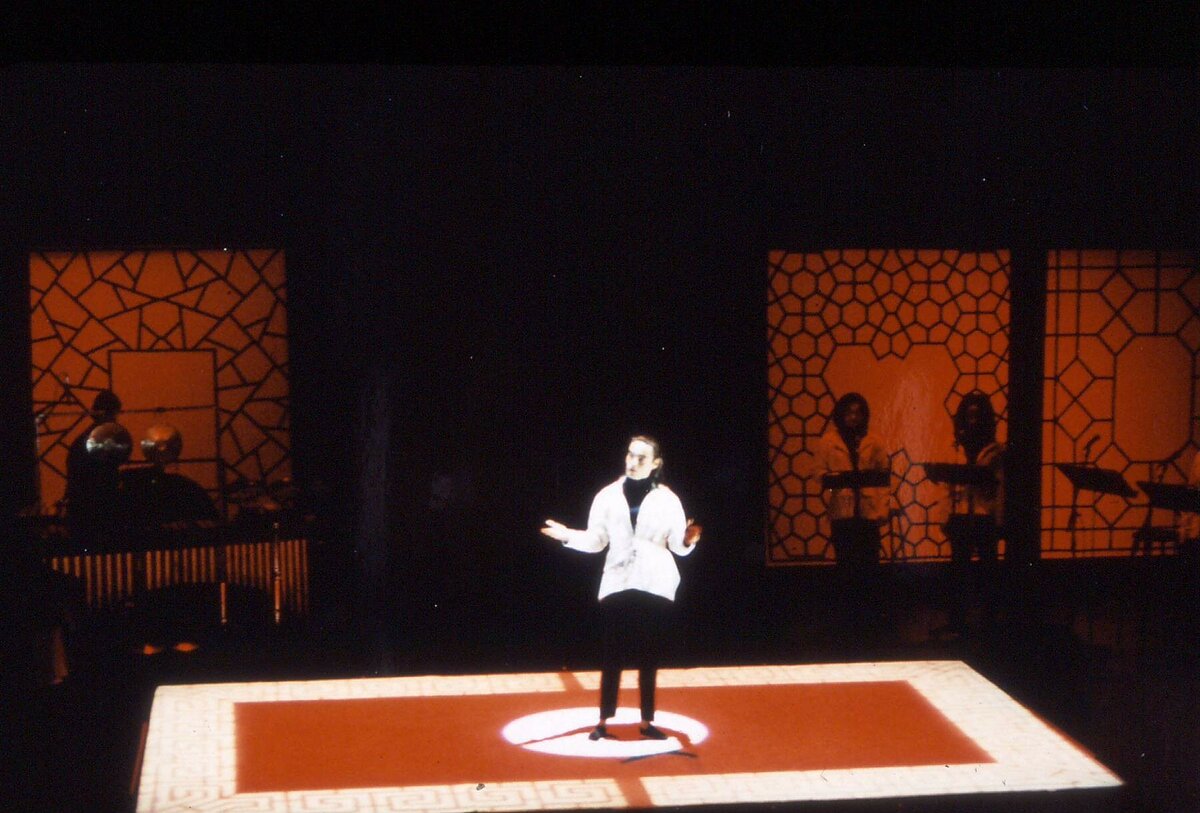

PC: In the beginning, I was pretty autocratic because I was coming from a visual arts background. With visual art, you have a canvas and you put something on it and that’s how I was treating the actors. For the first decade, the works were much more visually oriented instead of textual. There were some movement and dance elements. When the ‘80s started, I moved towards theater more in the traditional sense of using actors to act. That was a time where I was exploring how much media and visual art relates to the performer on stage. Can a piece be largely nonverbal and be mostly movement-based theater?

By the end of the first decade, we were devising together, because I didn’t know anything about writing a script. I had a company of performers; some were dancers, some were actors, some were mimes. It was kind of a mix of all these different performance art forms. They were the ones who helped me evolve my vocabulary. I would say the first decade was very clearly visual theater. The second decade was a mix of visual theater with theater-theater, so to speak. But the theater-theater portion was almost always stylized, still. It wasn’t realism. I almost never did realism. Maybe one or two works. I have done shows that are relatively realistic where there are realistic scenes. But it’s still very stylized in terms of the shaping or structure of the work.

PC: I’ve been doing that one for over 30 years now. There have been over 65 different productions of it. It began as an installation at a gallery in New York called Artist’s Space, which still exists. They invited me to do an installation there when I was still working as a visual artist. This was in the Reagan years. I had said, “When Reagan comes in, that’s the beginning of intolerance in this country. This is when the right is going to rise.” This was also during the height of the AIDS epidemic. The gallery had a rotating monthly installation featuring work dealing with AIDS and I created a work called, “A Facility for the Channeling and Containment of Undesirable Elements.”

Several months before that, I was in Amsterdam teaching an intensive, radical stage design class. The students were international but they all spoke English or understood English. We would have lunch together and get drinks and when we drank enough, people would start speaking their own language. I wanted to use language as a strategy to remind white America that there are other worlds. “Undesirable Elements” was an opportunity to do a show with multiple languages. I was just interested in the music of language. When the curator at Artist’s Space asked if I would consider doing a performance within my installation, I thought, “here’s a chance for me to try this idea out of doing a performance with multiple languages.”

That’s how it actually began. The first performance was in the installation. It was a 40-minute prototype. When I did that first production I was flabbergasted. I didn’t know what I was doing. I had never done a show that was so textual for one thing. There’s no action. Everybody sits in a chair and talks. But it’s amazing how successful that project has been. The people in it were telling their own stories. They were not actors. They were themselves. The power comes from that. I am retiring as Artistic Director of Ping Chong company but I’m working on a new piece, Undesirable Elements: Ukraine. It’s been an intense and incredible experience. I’ve already interviewed all the people that will be in it.

PC: I grew up in an insular community, which was Chinatown. My culture was completely Chinese, except for whatever was on television. My elementary school was probably around 98% Chinese; there were maybe three Italians in my class. I went to junior high school right across Canal Street in Little Italy where it was mostly split between Chinese and Italian students. That was where I made my first white friend. He was Welsh American and was always getting beaten up. I tended to gravitate toward people who didn’t belong.

When I started at the High School of Art and Design, I definitely experienced culture shock. I was the only Asian in the whole high school of 500 kids. By the time I left high school, there were four Chinese kids. And then I went to Pratt Institute, where again, I was completely alienated. In high school for some reason I didn’t feel it as intensely. But when I was at Pratt, that was when that feeling of being Other became very heavy for me…very heavy.

I lasted two years there. I was very unhappy. I decided to transfer to the School of Visual Arts to study film where I was a couple of years older than the other kids. I think I had a little more confidence because of that. But still, when I left that and met Meredith Monk, I still felt like an outsider. Meredith motley crue consisted of all kinds of strange people and even there I didn’t feel like I completely belonged. I just felt like I was standing aside a little bit during those first 10 years working with Meredith. She was very welcoming, but it’s just that I didn’t know where I belonged because I had left Chinatown and I was in this world that I wasn’t 100% comfortable in.

During my high school years, I was acculturating myself to white values. As a Chinese kid, if you go out with friends, you take them all out and you pay for them, if you can. I grew up working, so I had money. My parents paid me for my work. But that’s not the way it works in white culture. There were all these things I was trying to learn.