What the Early Closing of “KPOP the Musical” Tells Us About Representation on Broadway

On December 11, 2022, the final curtain closed on KPOP the Musical after only 17 shows. Following the performance, there was a post show talkback, where Tony-winning playwright David Henry Hwang summarized his feelings about the musical and the events surrounding it with three words: “proud, joyful, and angry.”

Like Hwang, I felt pride in KPOP the Musical being on Broadway. As a Chinese American, it was empowering seeing fellow AAPIs centered in the story, which follows the fictional struggles of the boy band F8, the girl band RTMIS, and the solo artist MwE, who all belong to a Korean music label called RBY Entertainment.

I also shared Hwang’s joy at the sheer maximalism on display in the dazzling song and dance numbers. And, full disclosure, I felt much pride and joy in seeing my partner Jully Lee make her Broadway debut in KPOP as the strong-willed CEO of RBY Entertainment.

But like Hwang, I also felt anger at the show’s short run. After the talkback, I emailed Hwang asking him to elaborate on this specific emotion. He wrote back “I’m angry that this amazing show never got a chance to find its audience, despite all the hard work and artistry that went into its creation.”

I have no doubt that one factor in the show’s early closure was KPOP’s chilly reception from Broadway gatekeepers. The New York Times’s chief theater critic Jesse Green penned an incompetent review of the production, which I annotated in detail on Facebook and Instagram, highlighting the review’s factual inaccuracies, basic misunderstandings of dramatic structure, cultural insensitivities, and its racially problematic language. Of the latter, Green referred to Jiyoun Chang’s lighting design as “squint-inducing” without clarifying who exactly was doing the squinting. Was it the mostly AAPI cast or was it the audience which also typically consisted of many AAPIs?

Especially galling was the critic’s assertion that knowledge of the Korean language was required to enjoy the show when there were only a few scattered phrases of Korean dialogue, not enough to warrant such a negative disclaimer. It also smacked of a double standard against AAPIs when other successful shows like The Lion King, The Light in the Piazza, and In the Heights have featured a similar amount of foreign language content without turning off their audiences or requiring a disclaimer.

But despite the discouraging reception, the subtext of this Broadway gatekeeping still acknowledged, implicitly perhaps, that* KPOP* was breaking new ground on Broadway. Even the most pearl-clutching critic had to admit their glaring ignorance of the K-pop genre, an ignorance decidedly not shared by the general American populace that has catapulted groups like BTS and BLACKPINK to household name status. BTS alone has had six number one singles on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100, the most by any single artist so far this decade, and six number one albums on the Billboard 200 chart.

It’s a fact that K-pop music has become one of the biggest recent trends in American media. This means KPOP’s composer/lyricist Helen Park (Max Vernon co-wrote some of the songs as well) is updating Broadway’s sound palette much the same way Jonathan Larson did with Rent and Lin-Manuel Miranda did with Hamilton and In the Heights. In Larson’s own words, “the American musical has always been about pop music.” Using Larson’s rubric, Park is not some gatecrasher, but instead is helping to ensure the Great White Way stays relevant for a new generation.

Meanwhile, to suggest KPOP do away with its use of the Korean language would be an erasure of its authenticity. A lot of the Billboard-charting K-pop albums and songs crossed over to the American charts with Korean lyrics, leading The Guardian to declare back in 2018 that “English is no longer the default language of American pop.”

If the goal of KPOP the Musical had been to appease white theater critics, perhaps KPOP’s creative team would have included more exposition explaining AAPI culture and history. It might have adjusted its score to conform to the aesthetic of traditional Broadway showtunes. One might imagine this approach would lead to greater mainstream success.

However, when another AAPI-created and AAPI-centered musical, Allegiance, tried that exact approach on Broadway in 2015, it was criticized in The New York Times for being too explanatory (“Allegiance often feels more like a history lesson than a musical”) and too tradition-conforming (“as if [Allegiance composer Jay] Kuo has long kept Les Misérables and Miss Saigon on permanent rotation on his iPod.”). This cold reception amounted to 111 performances of Allegiance on Broadway and no Tony nominations. It appears AAPI artists writing about their community are damned if they conform and damned if they don’t.

By contrast, the original 2017 Off-Broadway production of KPOP did win over critics. In fact, that show was nominated for Drama Desk and Drama League Awards and won Best Musical at the Lucille Lortel Awards. Produced through Ars Nova, the Off-Broadway KPOP was an immersive backstage tour of the musical acts as if the audience was an American focus group trying to help a fictional label break into the impenetrable American market. In a way, by centering a white mainstream perspective and displaying AAPI culture with all the comfort of a museum exhibit, the Off-Broadway version of the show did manage to conform to mainstream expectations.

However, the Off-Broadway success too presented a dilemma. The popularity of K-pop music had skyrocketed in the years after 2017, making the “impenetrable American market” storyline now obsolete. In 2022, K-pop music was now part of the American vernacular, and the creative team had to adapt to that new reality. The idea of presenting KPOP authentically without the white-centered frame had once seemed unthinkable. Now it was a possibility to be considered.

In light of this, I find Helen Park’s choices as a composer, music producer, and arranger to be invigorating for the AAPI community. For one thing, she flouted the conventional wisdom that you can’t feature today’s pop music on stage in an authentic way. It’s a well-known dictum that Broadway lags behind the times in music trends. “A prominent Broadway musical director once told me that Broadway music is generally about 20 years behind popular styles,” wrote David Henry Hwang in his email to me.

Hwang’s director friend might have been a bit generous. A monologue from the stage version of Larson’s* Tick, Tick… Boom!* declares Broadway’s lag is closer to 60 years. Combine that with the lag in musicals by and about AAPIs to make it to Broadway (Allegiance was the last one, and it premiered seven years ago), and Park had a tall order to fill. Yet, even against such odds, Park made her Broadway debut by not appeasing the gatekeepers but instead keeping true to K-pop’s nowness.

That decision is even more startling when you realize that Park is more than capable of writing a traditional showtune. She honed her musical theater writing both at NYU and in the BMI Lehman Engel workshop where the alumni of both organizations read like a who’s who of Broadway. In fact, her original songs in the Netflix animated film Over the Moon are as traditionally musical theater as those in any Disney film. Park could have easily watered down her KPOP music and leaned into the more well-worn path of appeasement.

Instead, Park created an authentic and unapologetic score that asks the audience to take AAPI culture on its own terms. But far from alienating audiences, her songs are also full of English language lyrics that clearly express the show’s themes and emotions. And the electrifying and infectious K-pop sound she wields is currently popular all over the world for a reason. The party atmosphere of the show’s 20-minute finale was often filled with audience members of all stripes spontaneously clapping along and dancing in their seats, a testament to this music’s inclusivity.

It also helps that Park has immaculately produced an album’s worth of earworms. Speaking of which, the Broadway cast album is set to drop on February 24, 2023. I’m guessing that once Park’s soundtrack reaches a mainstream audience (one that doesn’t mind Korean lyrics and bold electronic music), the conversation around KPOP the Musical’s cultural impact might change as well.

After all, Stephen Sondheim’s famous flop Merrily We Roll Along, which had only 16 performances (one less than KPOP), similarly rose in stature after its closing due in part to its cast recording. In fact, Merrily’s reputation has improved so much that a new production starring Daniel Radcliffe just announced its Broadway transfer in 2023. Could KPOP have a similar revival in its future?

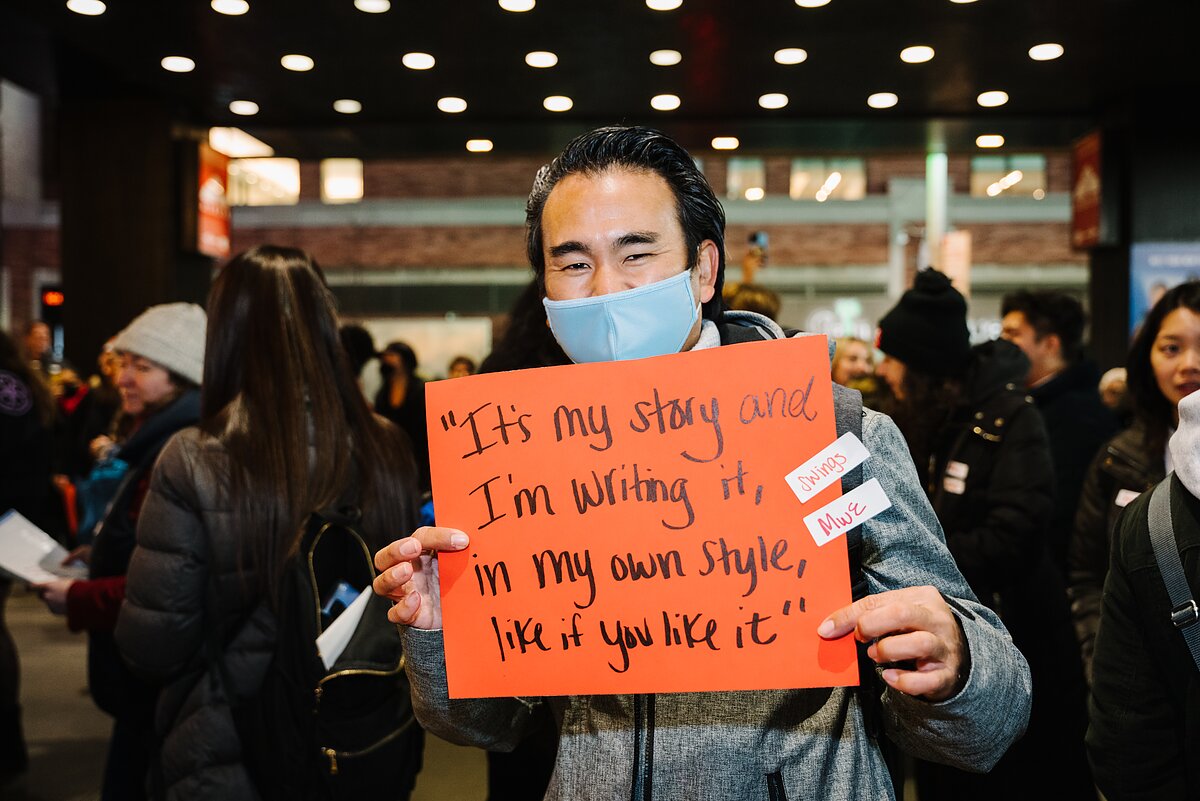

Judging by the final days of KPOP on Broadway, there is certainly a demand for it. A rally outside of Circle in the Square Theatre (where KPOP was performed) brought together fans of the show, fans of K-pop, and members of the Broadway and AAPI communities in a bittersweet celebration the night before the musical’s closing. TV news crews caught footage of the crowd filling Gershwin Alley chanting “KPOP KPOP KPOP!” The cast even came out in street clothes to perform numbers from the show reminiscent of the days when the Hamilton cast would come outside and serenade their crowds. Meanwhile, on social media, the hashtag #SaveKPOPBroadway was trending, and KPOP continued to receive supportive posts from celebrity fans like Lin-Manuel Miranda, Andrew Yang, and Jeremy O. Harris.

So ultimately, I’m hopeful. Perhaps Park put it best when she was asked in the KPOP talkback for her own three words to summarize her feelings. She said, “I won’t stop.”

Howard Ho is a writer, composer and YouTuber. His YouTube channel “Howard Ho Music” has over 100,000 subscribers and has been recognized by Lin-Manuel Miranda. He was an O'Neill National Playwrights Finalist and had an original musical featured in the Samuel French Off Off Broadway Short Play Festival. His journalism has been published in the LA Times, Entertainment Weekly, Howlround, and American Theatre magazine. He has sound designed over 50 theatrical productions and has been nominated twice for Ovation Awards in sound design. He’s studied improv with Freestyle Love Supreme and Cold Tofu and holds degrees from UCLA & USC.