Director David Siev on Understanding the American Dream

In the spring of 2020, David Siev did what many young people did during the early days of the pandemic; he moved back home to be with his family. For Siev, that meant returning to Bad Axe, Michigan, a small town of just over 3,000 citizens located squarely in the famously mitten-shaped state’s thumb.

As a filmmaker, Siev immediately began recording his family. In doing so, he captured the personal, intimate ripples of 2020 in real time, documenting the effects of the pandemic on his family’s restaurant, Rachel’s; the nuances of intergenerational trauma as a Cambodian Mexican American family; and the backlash that resulted from his family’s allyship with BLM in a town that is 97% white. Titled Bad Axe, the documentary is a deeply vulnerable, honest account of family, community, and resilience.

Originally a crowdfunded endeavor, the film has since picked up distribution from IFC and has signed on industry veterans Daniel Dae Kim and Jeff Tremaine as executive producers. Among its now innumerable accolades, Bad Axe has won Special Jury Recognition and the Audience Winner prize at SXSW in 2022, a Critic’s Choice Award, and is currently on the shortlist for this year’s Oscar nominations for documentary film. The documentary is currently available to stream.

After the film’s NYC debut at IFC Center, The Amp’s Shannon Lee sat down with Siev to discuss the making of the documentary, what its reception has meant for both him and his family, and how it has deepened his understanding of the American Dream.

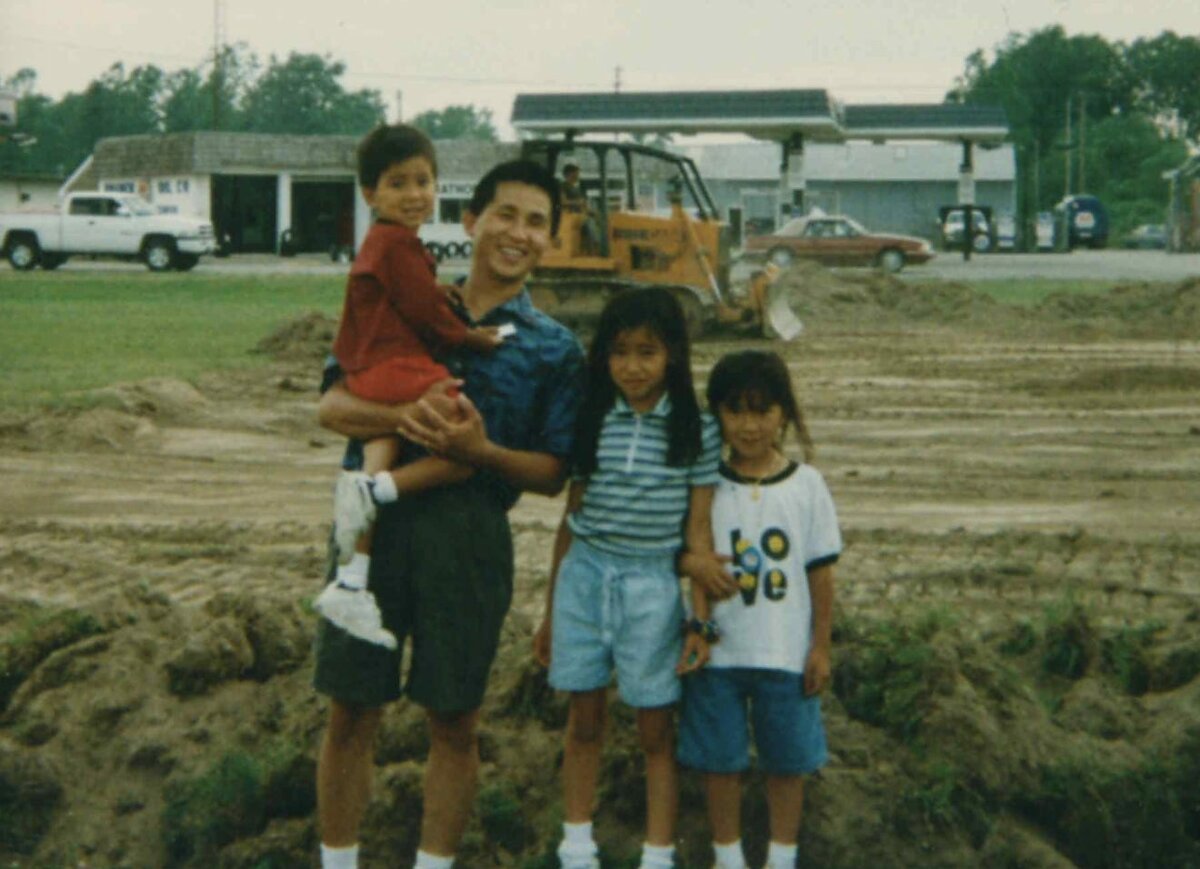

David Siev: I had just moved back home to Bad Axe, Michigan from NYC. When I picked up my camera and started filming, it wasn’t like it was the first time I’d done something like that. I’ve always loved filming my family, bottling them and our memories in photographs and home videos. Having said that, I’ve always wanted to share my family’s story for years. My parents are a Mexican American woman and a Cambodian refugee who came to this country in 1979. Together, they decided to settle, of all places, in Bad Axe, Michigan, and raise a family and start a business. They struggled for years to get it going but eventually turned it around and made it a success. It’s this classic American Dream story that I wanted to get out into the world.

When I began filming, it was really just about capturing those stories and having them on camera as something that I could look back on. Little did I know that this story that I had always wanted to share was unfolding itself in front of my eyes in the form of a documentary through all these home videos I was capturing. With the pandemic and the racial reckoning our country went through, the American Dream is still being challenged. It became very clear that the story I’d always wanted to share had to be told through the backdrop of today and through documentary filmmaking.

DS: I think making Year Zero, which is a narrative short, was the beginning of this journey of telling my family story. That particular short film focuses on one of my dad’s stories of surviving the Cambodian Killing Fields and the Khmer Rouge when he was a 16-year-old boy. It’s about how he stole a cup of rice from a warehouse. During that time, if you were caught committing any petty crime, the sentence was death. It’s about how he escaped the hands of death over something that we take for granted every day. Telling that story was the beginning of my exploration of my dad’s past and my family’s roots. It became very clear when making Bad Axe that I would need to pull back the layers of my dad’s past and his history to inform who he is today. Including scenes from Year Zero was the best way to depict that.

There’s also not a whole lot of archival footage during the time of the Killing Fields so including scenes from my short film was the best way to visually tell his story.

DS: The film’s ending was decided when the actual film ends; when the surprise miracle comes and brings the entire story back to being about family and generations and turning over a new leaf. About how our lives are all possible because of my grandmother who came to this country in 1979 as a widow with 6 kids. Seeing how that resilience gets passed along from each generation to the next, it was very clear that there could have been no other ending. It had to come back to being about family and tying together this generational element of resilience. The moment that last scene happened, I knew that was the ending of the film. I went home that exact night and I edited it all together—and that was it!

It didn’t feel right to end the film with the election. While you see how important that moment was for our family, that’s not the point of the film. I’ve seen firsthand how this movie transcends politics. People can relate to our family and see themselves in our struggles regardless of where they are on the political spectrum. The fact of the matter is that 2020 was something we all went through together as a country. You’re just seeing this experience through the very specific lens of this multicultural family in Bad Axe, Michigan. By the end, I hope the film gives everyone a sense of hope for the future regardless of how they feel about the politics in this country or whether they agree with our family’s opinions.

DS: When you make something so personal and you put it out into the world, you don’t know how people are going to react. You hope how people will react; that they’ll connect with it in their own personal ways. I’m so grateful that has been the case with this film, with critics and audiences all across the country. The feedback that has been the most meaningful has been when we had the opportunity to screen the film in Bad Axe.

In the meta journey of the film, you see how community members reacted to the film before they even had a chance to see it. You see the backlash; that the film is a smear piece of Bad Axe and that it’ll paint the town in a bad light, which is so far from the truth. When we had opportunities to screen the film there, we were very anxious. How is the community going to react? Granted, so many community members have been supportive of the film since we first put out the trailer. That’s the reason why we were even able to complete our fundraising goal on IndieGoGo. But there were still negative voices and at times, those voices spoke a little louder than one would like.

But after showing the film in Bad Axe and witnessing a lot of those skeptical community members come into these screenings…and I’m talking about the same people leaving social media comments or stopping my mom at Walmart saying they didn’t want to support the restaurant anymore because of what I was doing. At every Q&A, there was someone who would raise their hand and say, “I might not agree with your family’s politics but thank you for opening up my eyes to an experience I didn’t know existed in Bad Axe, Michigan.”

That has been the most profound and powerful response that I’ve witnessed with this film firsthand. I say that because these individuals are no longer looking at us as the other. They’re seeing us as their fellow community members and their fellow Americans. They see that our experience in Bad Axe and all throughout 2020 is the American experience. The American experience isn’t just for white people; it’s for immigrants and refugees and the BIPOC community. That’s all part of the American experience.

The way that all changed was by being able to have a dialogue with one another. But that dialogue can’t really begin until we can look at each other as human again. In engaging in that conversation firsthand, it really opened up my own eyes to the power of cinema. As filmmakers, we always hope that films have the capacity to invoke change but being able to witness that firsthand with my own film and my own community is so meaningful. I’m so grateful for that.

DS: This film is completely DIY. When I started making it, I started with my wife, who is my producing partner and my first editor, Peter Wagner, who is a friend. The three of us were on this journey together. We slowly started to get more producers (Jude Harris and Dianne Kwon) and another editor named Brosey.

A lot of documentaries are made with small teams but not a whole lot of them succeed in getting the distribution plan that Bad Axe has gotten. Distribution is really hard for a film like this. Leading up to SXSW where our world premiere was, every sales agent passed on us because they thought the film was too personal. Every major distributor passed on us saying that they didn’t think the film would reach audiences. That was so discouraging.

By that point, I had put everything into this film. I had maxed out all of my credit cards and had $101.99 in my bank account. Being told by the industry that they didn’t think there was an audience that would connect to it… Going into a festival, the dream is that the right person will be in the room and will buy it. That wasn’t looking like that would happen at all. I felt like my back was against a wall. If a deal didn’t happen, I would probably have to move back to Bad Axe and work at the restaurant again to get myself back on my feet. I was preparing myself for that reality.

But during the film’s premiere at SXSW, there was someone in the room from IFC. There was so much love from the audience; we got a standing ovation. It felt like a dream come true in so many ways. A week later, we ended up getting an offer from IFC films and I was able to pay my rent and get myself out of credit card debt. This whole journey has felt like a dream because distribution is something that every filmmaker dreams of but it can never be expected. And after being told “no” so many times, I was very discouraged. I feel like I am living my American Dream right now; not because I was able to sell my film and go on this journey with all of these accolades and awards but because it’s given me the courage and empowerment to speak up and know that our stories matter. I didn’t quite feel that I had that before.

I think that’s how the American Dream has shifted from my parent’s generation to mine. For them, it was so much about survival; keeping a roof over our heads, food on the table, and being able to work hard enough to send their kids to school. I think for us, it still entails all of the financial stability but there’s this other element of being able to have a voice and be viewed as just as American as anyone else. This film has given me that.

DS: They’re all doing great! We’ve been on the road for 9 months going to film festivals across the country. It’s been so amazing having my family be a part of that. Prior to this whole experience, my parents never really got to travel anywhere. Our idea of a vacation growing up was driving 3 hours up to Toronto and spending Sunday and Monday there once a year. This year, they’ve seen every pocket of this country.

Since the film, community support for the restaurant has grown exponentially in some ways. It’s so incredible to witness people wanting to come into the restaurant and meet up. [My youngest sister] Raquel and [her boyfriend] Austin are there every day. That’s the only reason why my parents and Jacqueline have been able to travel. They’ve really embraced their role and have come to love what they do and what the restaurant represents. It’s really amazing to witness all of this firsthand. We’re all so grateful for where we’re at as a family. The babies are a lot of fun too; they just started walking a few weeks ago.