Lily & Honglei on Using Old Stories to Heal New Wounds

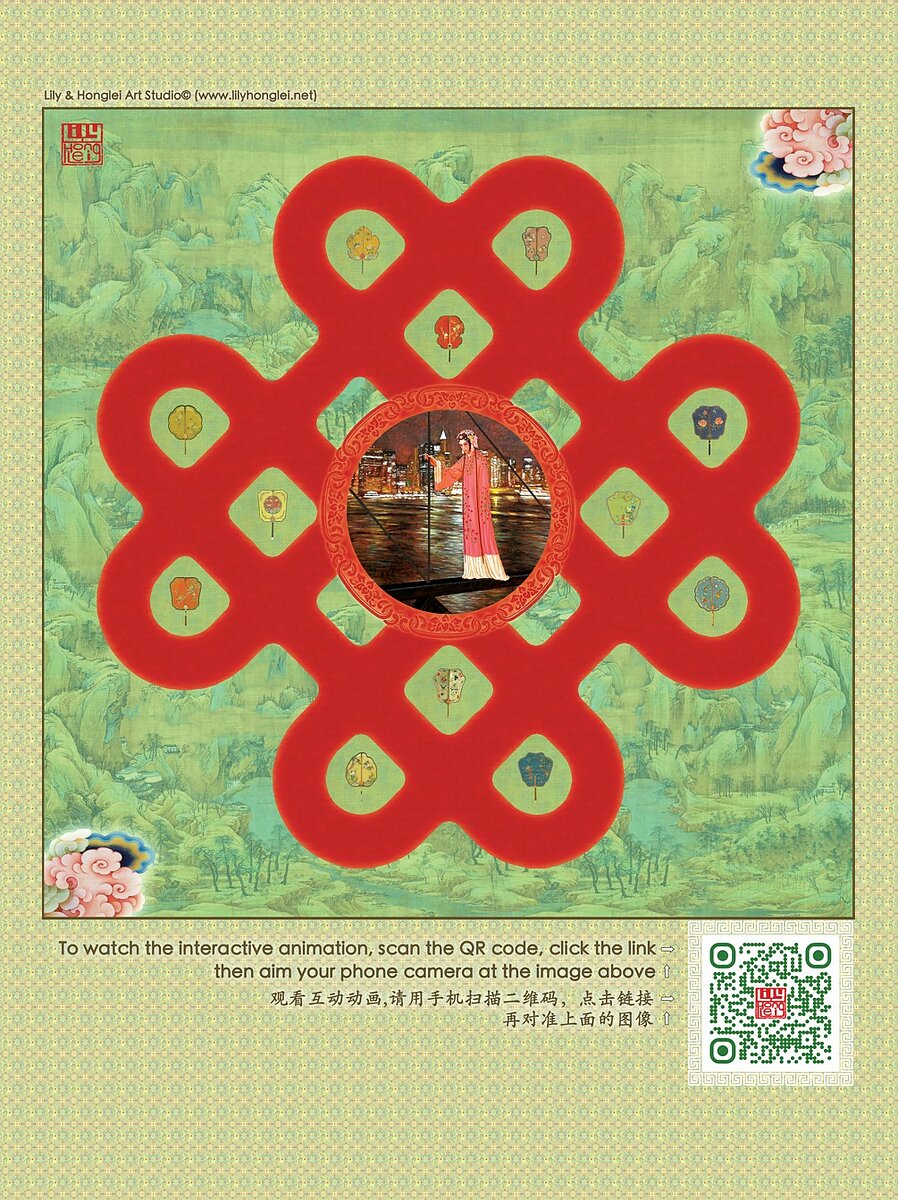

For the interdisciplinary artist couple Lily & Honglei, augmented reality is a bridge that allows them to connect gaps in time and space in order to create spaces for healing. Their current public art installation, “The Red String,” uses the technology to animate their paintings and bring traditional Chinese folktales into present day NYC. Hung at Flushing’s Bowne Playground and Chinatown’s Columbus Park, eight vinyl banners display beautifully rendered paintings adorned with the titular knotted red string, which traditionally symbolize unity and love.

Commissioned by More Art and up through December 19th, each banner includes a QR code which, when scanned, animates the paintings on the viewer’s phone. The animations are adaptations of centuries-old Chinese stories, told within a contemporary context in order to reflect on the immigrant experience. “We found a lot of similarities between Asian immigrants’ life and ancient Chinese folk stories,” said Honglei. “Those hundred-year-old stories can be easily related to people suffering today.”

The Amp’s editor Shannon Lee spoke to Lily & Honglei about their work, their use of augmented reality, and their experiences as Chinese immigrant artists living and working in NYC.

Lily: We are long-term residents of Flushing’s Chinatown. Since the pandemic began, we have witnessed how the local economy got hit hard, with so many businesses shutting their doors permanently and so many residents losing their jobs. Even worse, Asian immigrant community members, especially the elderly and women, became the targets of Asian hate violence. Many of our family members and friends living in the Flushing area were forced to live in isolation because of the fear of being attacked on the streets. The only outdoor places they still visited were a handful of public parks in downtown Flushing where they could get together to play chess and cards, exercise, or babysit.

As artists, we are really heartbroken by the isolation that our community members have been suffering. Because of cultural and language barriers, isolation has been a long-term issue for Asian enclaves in Flushing, which has the largest number of Chinese and Korean immigrants in New York City. The pandemic drastically exacerbated the problem. Some of our friends and family members experienced mental breakdowns due to the isolation. This situation motivated us to create a public art project which can bring healing and make a strong voice for the Asian immigrant community.

Through “The Red String,” we intend to spotlight the cultural heritage of Asian immigrants. In our experience, cultural heritage can bring community members together through its strong healing function. We also hope that by sharing our cultural heritage through public art, other groups of people in the city can grow their understanding of the Asian immigrant community.

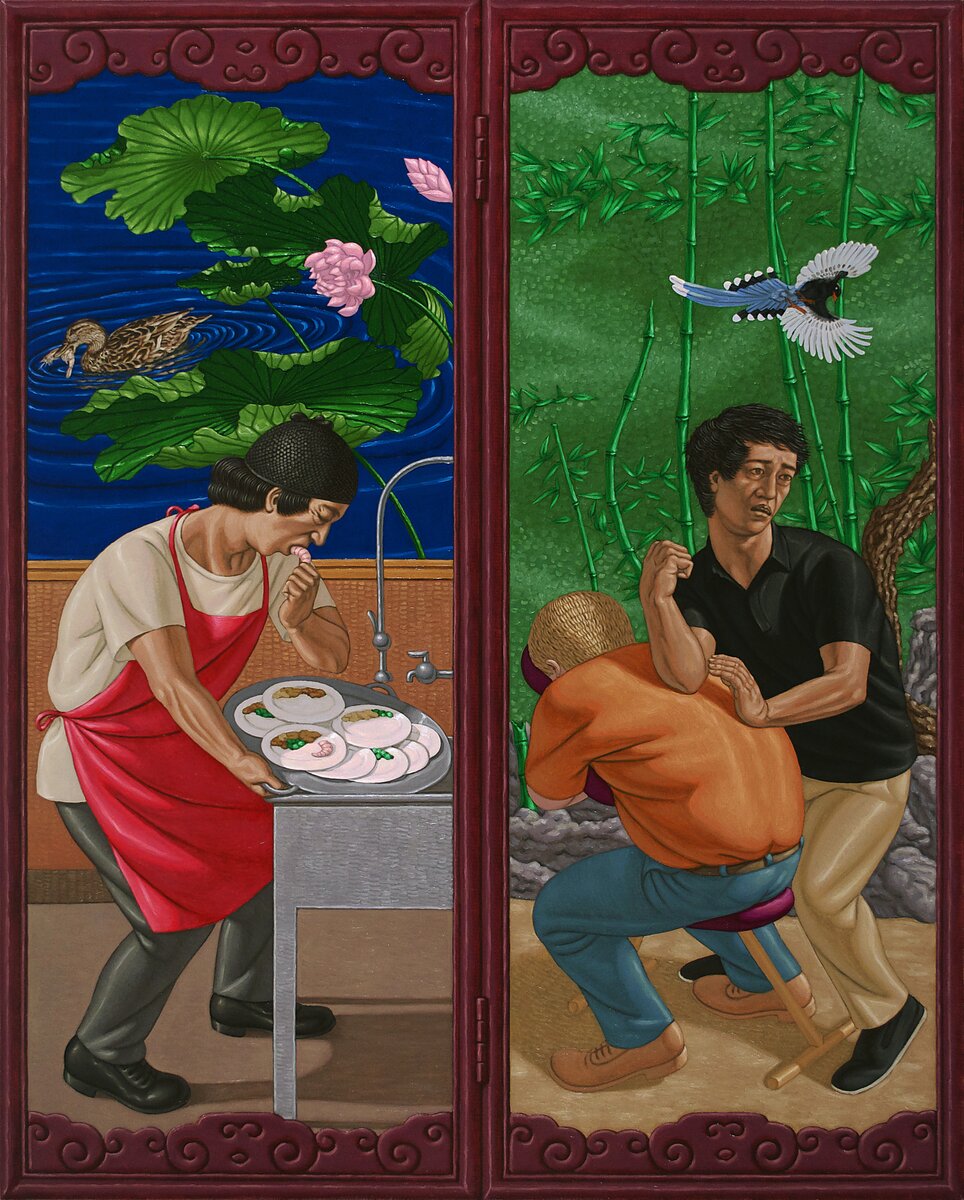

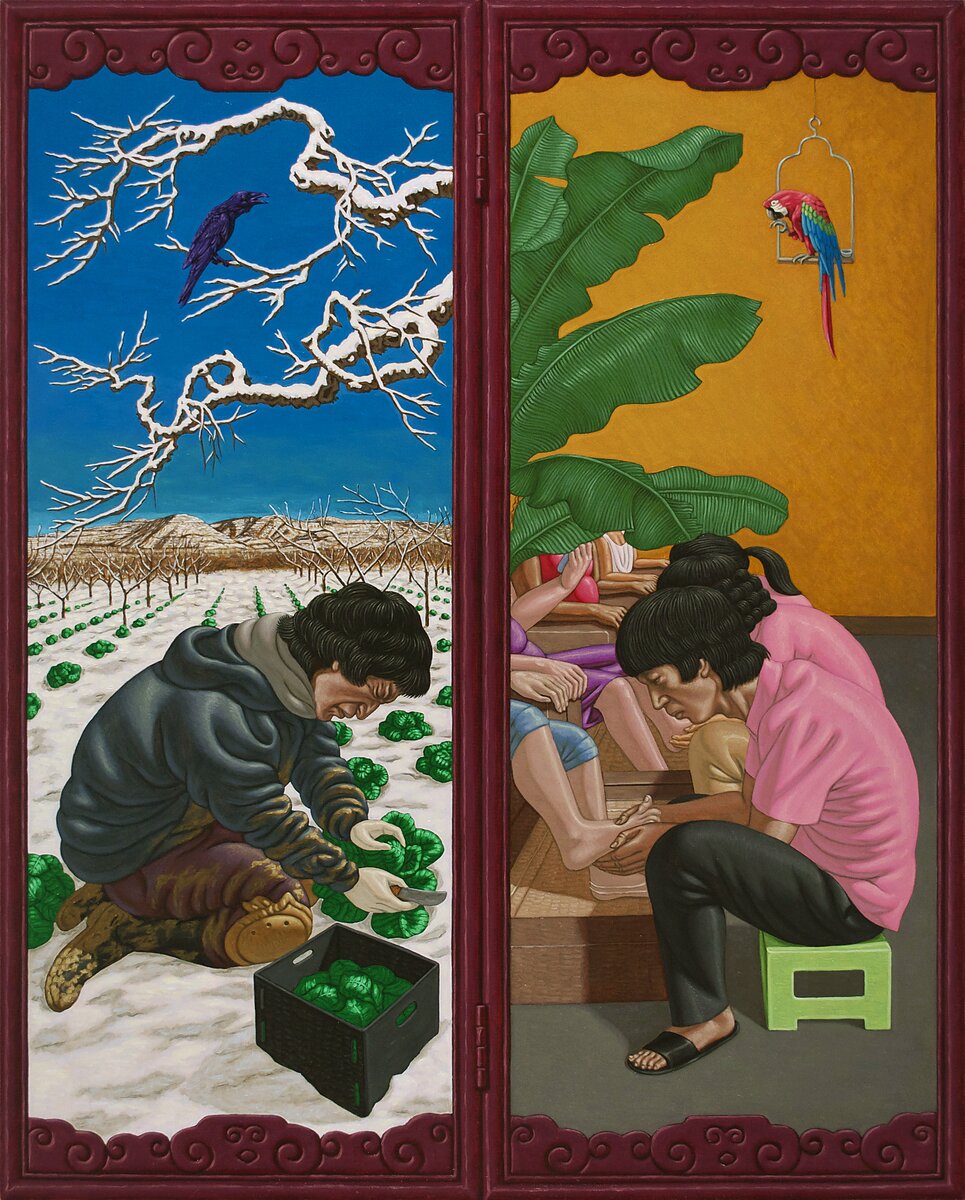

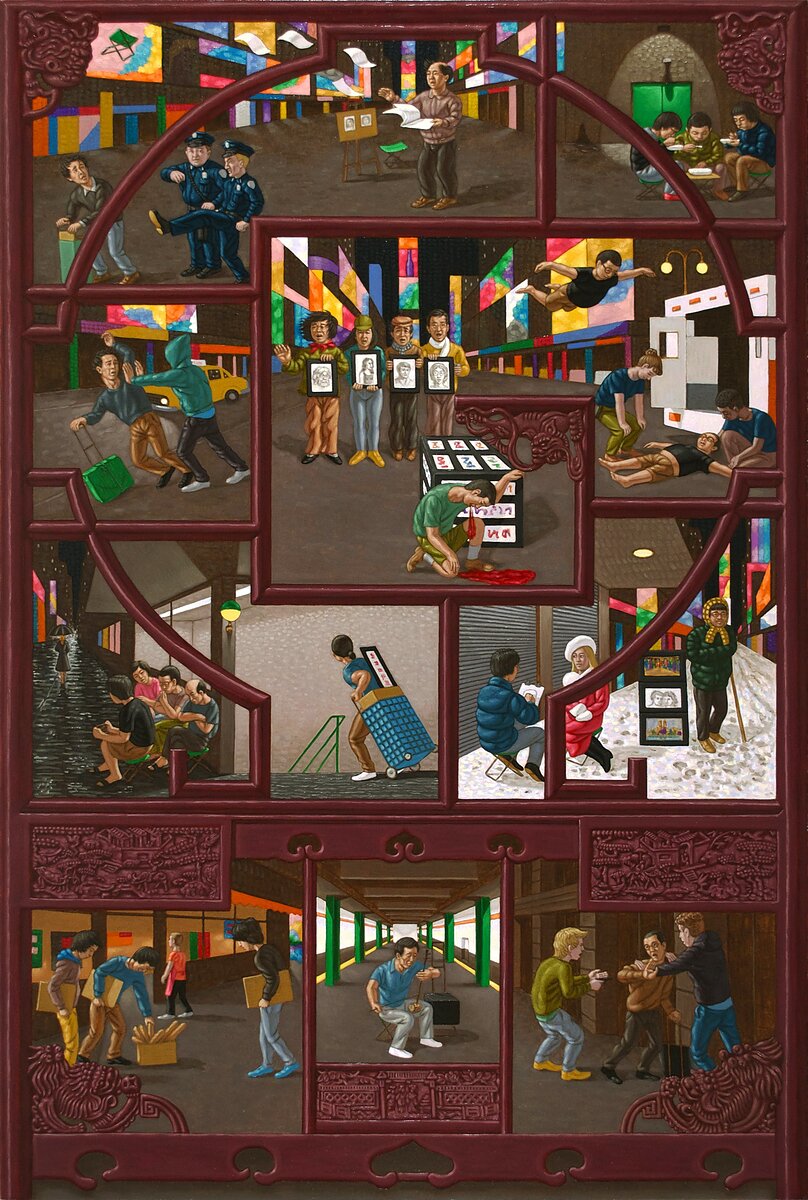

Honglei: The stories told in “The Red String” are based on our immigrant experience, as well as some ancient Chinese folktales. Some animations feature works from our painting series, “Life of the Invisibles.” One of the stories is about Lao Liu, a real person who I met when I worked in a Chinese restaurant in NYC. He worked many low-paying jobs such as in a vegetable farm, nail salon, doing massage, renovation, and finally collecting bottles and cans on the street. These are typical job options for Chinese new immigrants.

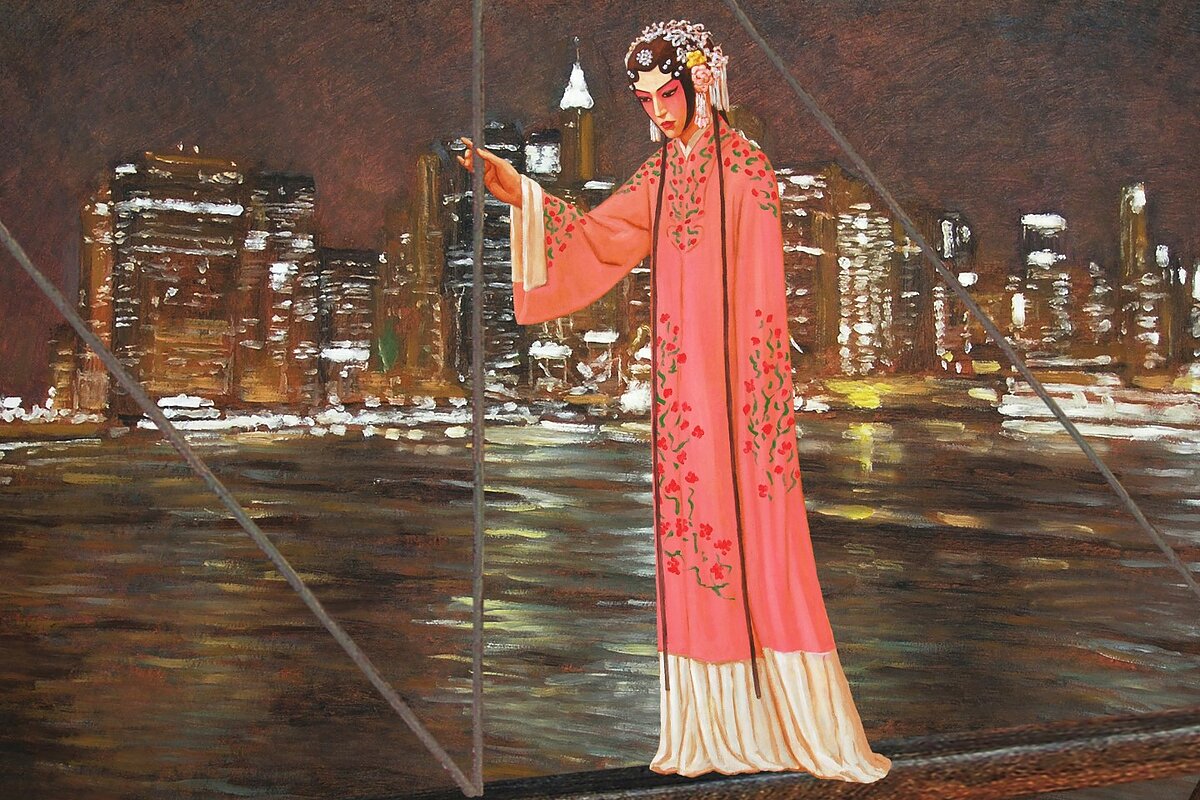

We found a lot of similarities between Asian immigrants’ life and ancient Chinese folk stories. Those hundred-year-old stories can be easily related to people suffering today. We place the ancient characters in today’s American society to reflect the isolation, family separation, and hard conditions in new immigrants’ life. In the work, Butterfly Lovers, we reinterpret the namesake Chinese folktale. This thousand-year-old legend depicts a tragic love story often regarded as the Chinese equivalent of Romeo and Juliet. The animation reimagines the scenarios from the original story, illustrating the butterfly lovers dressed in traditional Chinese opera costumes, roaming Times Square, Brooklyn Bridge, the subway station at night.

Honglei: The public reception has been quite enthusiastic. There are indeed some different forms of engagement between the two installations in Chinatown and Flushing. We think this is because of the demographic difference between these two neighborhoods. In Chinatown, besides Asian Americans, many audience members are tourists and young people. When they saw the banners at Columbus Park, they immediately took out their phones and tried the ARs. They are curious about AR technology and eager to learn about Chinese cultural heritage through interactive art.

In Flushing, most audience members are Asian immigrants, especially seniors gathering in the park on a daily basis. They like to take their time checking out the details on the banners. When we were photographing the installation at Bowne Playground in downtown Flushing, some visitors to the park chatted with us. Given their cultural background, they have a deeper understanding of the design elements, the folk stories, and the traditional Chinese music in the animations. Many passersby told us they love the colorful banners. They are excited to see that there is finally a public art project designed to spotlight their cultural heritage. Once, we found that a banner was a little bit broken on the edge, and someone carefully fixed it with tape. It’s quite heartwarming to learn that community members really enjoy and cherish the artwork.

Honglei: Our practice in AR started around 2010. We collaborated with the pioneer AR collective called Manifest.AR on numerous projects, interventions, and exhibitions around the globe. During that period, we focused on creating location-based AR, which is invisible to the naked eye and can only be viewed on smartphone screens.

The Tankman AR is a good example of this. Collaborating with Boston-based media artist John Craig Freeman, we launched a 3D model at Chang An boulevard near Tiananmen Square, where the student protest took place in 1989. The AR technology allowed us to launch the artwork in Beijing while we were physically in the US. What we intend to achieve with this project is to create a virtual memorial for the victims of the massacre, reminding the world the spirit of the student protest remains alive. And it could be proven by what is going on currently in many cities in China, where more and more people stand up to demand freedom and dignity against lockdowns and censorship.

Lily: As for what attracts us to AR, we think augmented reality is an effective channel connecting our studio art practice with social engagement. “The Red String” perfectly embodies this. “The Red String” combines several of our current and earlier projects, including several painting series and animations that took years to complete. Generally speaking, our projects often start with creating oil paintings on canvas and then composing short animations based on the painting series.

We have presented paintings and time-based artworks in many museums and galleries, however, we have always had a strong conviction that art should directly communicate with the public beyond the boundary of museums and galleries. Art can directly reflect realities and deliver meaning and beauty to audiences in public spaces, including both physical and cyber space. The smartphone AR technology allows us to present our paintings and time-based artworks in outdoor settings such as public parks within a limited budget.

For “The Red String,” we spent months figuring out the best AR solution that is easy and fun to use for the viewers. It doesn’t require installing any additional apps on the phone. In the park, visitors can simply scan QR codes on the banners with their smartphone cameras and watch the banners come to life through web-based augmented reality.

Lily: Meanwhile, we feel the urgency of using our art to fight the current Asian Hate crisis. So we are developing another series, “Asian American Mythology.” One work is titled 42nd Street. In it, we depict the moon goddess in Chinese mythology ascending from the place where Michelle Go got pushed to death at Times Square subway station. The painting serves as a memorial with the wish of a beautiful transformation of the tragic ending of Michelle’s life.

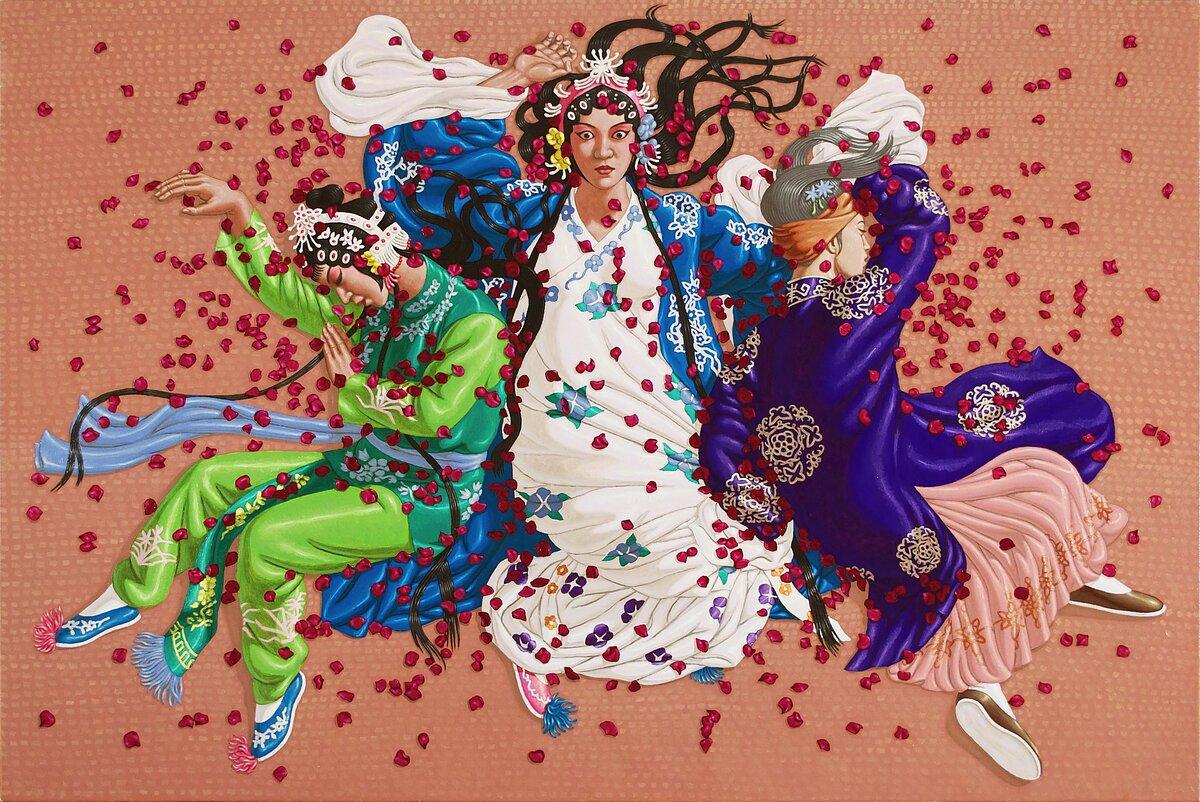

Another painting, Dream, Interrupted, is a memorial for the victims of the Atlanta massage parlor massacre. Inspired by the Peony Pavilion, we reinterpret the story that the lady’s dream is interrupted by falling petals to create a visual metaphor, reflecting the victims’ lives and the American dream shattered by the bloodshed.

Overall, we use these very popular traditional characters to reflect current societal issues and borrow the strong healing power from the old stories to heal our new wounds. We hope our art can contribute to enhancing the visibility of AAPI, spotlight Asian American cultural heritage that strengthens our collective identity, and ultimately, enrich the lives of more New Yorkers.