Vishavjit Singh on Becoming an American Hero

Not all heroes wear capes—but cartoonist, author, and activist Vishavjit Singh does, along with a turban, beard, and a Captain America costume shipped from Hong Kong. Motivated by the sustained Islamophobia that persisted in the wake of 9/11 (as well as the popularity of the Captain America film franchise), it was twelve years ago that Singh first appeared on the streets of New York City dressed as a Sikh Captain America.

Singh’s escapade was documented by photographer Fiona Aboud, who was working on a series about Sikh Americans at the time. Aboud’s photographs were published in Salon Magazine accompanying an essay by Singh, titled “Captain America in a turban”.

The article was a viral success. Since then, Singh has been featured and profiled in countless news outlets and publications, including CNN, NPR, PBS, and The New York Times. He has appeared on segments for late night shows like “Totally Biased with Kamau Bell” and has been invited to speak at schools, organizations, and events about his experience.

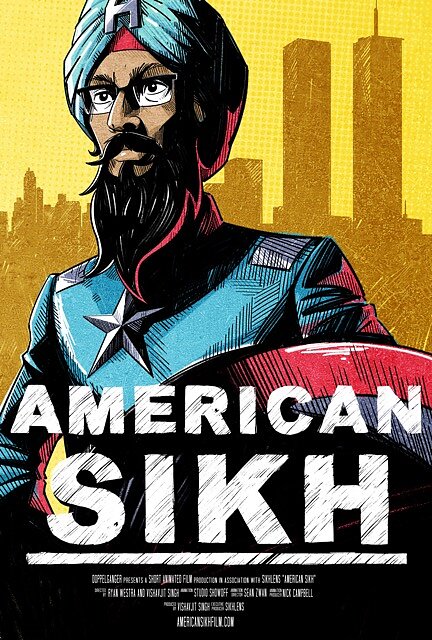

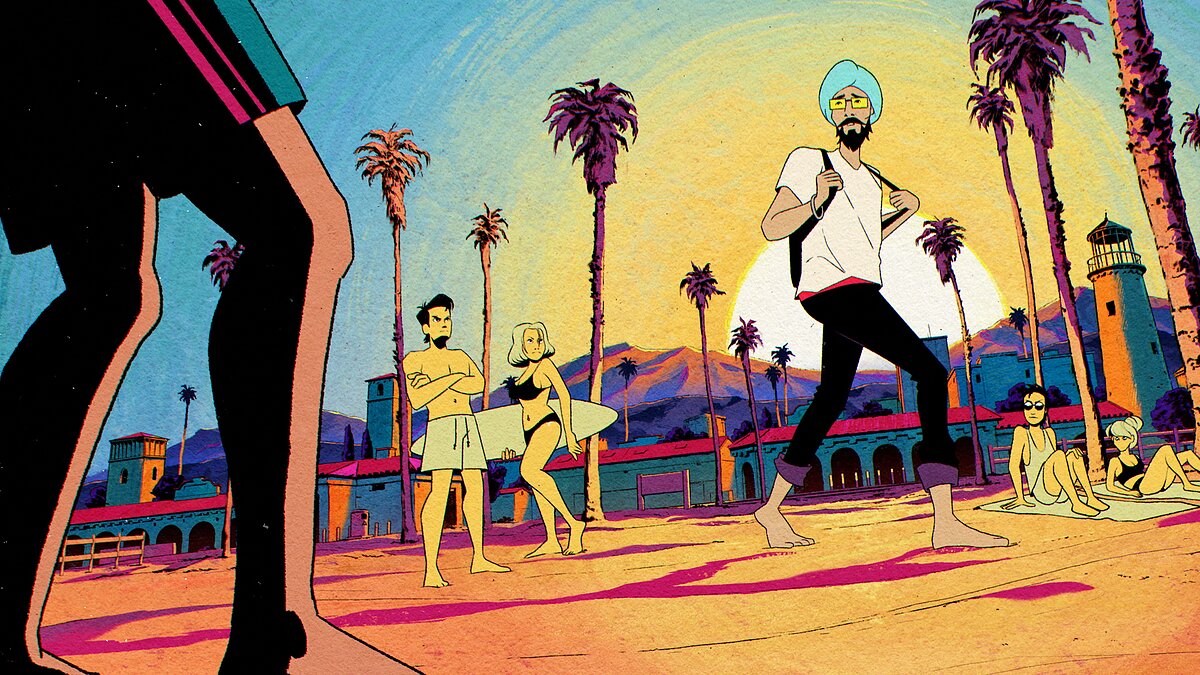

Last year, Singh revealed the man behind the hero costume in the animated short film, American Sikh. Directed by Ryan Westra and Singh in collaboration with Studio Showoff, American Sikh is Singh’s own hero origin story. Born in Washington DC, Singh moved to India with his family as a boy only to narrowly escape a 1984 genocidal massacre that saw thousands of Sikhs murdered. After high school, Singh returned to the US to attend UC Santa Barbara and UC Berkeley before moving back to the east coast. By then, it was 2000; mere months before 9/11.

The film—which premiered at Tribeca Film Festival and has received numerous prizes and accolades—has been released on Youtube ahead of the 23rd anniversary of 9/11 with an accompanying lesson plan inspired by the film. The Amp’s editor, Shannon Lee, spoke with Singh about American Sikh, the legacy of 9/11, and how Singh’s Captain America has evolved in meaning over the years.

Vishavjit Singh: American Sikh was actually an idea that my co-creator, Ryan Westra, came up with. He’s a filmmaker based in southern California. Our paths first crossed in 2014. He was graduating from Chapman University’s film school, which was a partnership with Sikhlens arts and film festival that focuses on telling Sikh stories. Students who are interested get to work with this film festival and receive opportunities to travel the world in order to tell Sikh stories in North America.

Ryan was given an assignment to go follow this Sikh guy in New York City who dresses up as Captain America. He and two other student filmmakers met me in the city and they followed me around for three days as I dressed up as Captain America. They created a short live action film called Red, White, and Beard that they decided to upload directly to YouTube instead of running through the festival circuit.

That film did quite well, especially with educators. Ryan got back in touch with me in 2018 saying that he wanted to tell my life story through film—Red, White, and Beard was just about my performance art activism. One of the first choices we made was for it to be animated. That was a very deliberate choice. There’s two tragedies that are very connected to my life story—one is 9/11 and one is 1984, a year where I spent part of my childhood living through the genocidal violence targeting the ethnic Sikh minority in India. My family narrowly escaped mob violence.

We were trying to figure out how we could best show these two very big tragedies through film. Tragedy in live action can be very intense but animation gives you creative license to frame events a certain way and leave things to the imagination. Neither of us had ever done animation!

VS: When 9/11 happened, I was living in Connecticut but working in Westchester County. I used to come into the city to take classes at the School of Visual Arts. For me, as a turbaned and bearded Sikh, 9/11 had a very immediate impact. Within a few hours, a friend of mine was arrested. I found out because I saw him on CNN.

Osama Bin Laden’s image started flashing on the news. My brother and I were working at the same company. We both knew immediately that our lives were going to be in danger. I was working for a tech company at the time so we were able to ask our boss if we could work from home for a few days, given what was happening. As an immigrant himself—he was Polish American—he understood.

We worked from home for a couple of weeks. Unfortunately, the first hate crime casualty was a Sikh man in Arizona. Anybody who was brown and perceived as Muslim was a target. I was taking all of this in and I remember looking at how editorial cartoonists were responding to 9/11 and its aftermath. I gravitated toward this. Some of them were very pro-American, but some of them were also very critical to how we were responding.

I remember seeing this one animated cartoon by the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist, Mark Fiore. It was titled, “Find the Terrorist.” It had fast rotating images of men’s faces. You had to click on the images to find out who they are—their name, what they do. The terrorist in that collection happened to be a white man who committed a hate crime against a fellow American he perceived to be not American.

VS: That cartoon simmered in my head for a few weeks. I started cartooning. My cartoons were eventually called Sikhtoons that featured turbaned and bearded Sikh men. Ten years into that journey, the first Captain America movie came out. In my mind, I thought, “Captain America should wear a turban and beard and should be Sikh!”

I illustrated that version and created a poster. Somebody had convinced me that I should go to NYC ComicCon as an exhibitor. The movie came out in July. ComicCon was in October. There were hundreds of illustrators. Something interesting happened with the poster. I wasn’t sure how people would respond to it. People thought, “interesting” or “cool.” Some people thought, “not cool” and “why is Captain America wearing a turban?”

A photographer who was working on a photo essay about Sikhs was documenting me at the time. Her name is Fiona Aboud, a Jewish Brazilian American photographer based in New York. We were struggling to find a great way to capture me so when she passed me by at ComicCon, she said she loved the poster and that maybe I should come back next year dressed as Captain America. I said absolutely not.

We didn’t speak about it for some time and were still looking for spots around the city to take my photographs. On August 5th, 2012, there was a white supremacist who killed six worshippers in a Sikh Gurdwara in Milwaukee. Police came and he shot a police officer who survived. I responded to that by writing an op-ed piece about how American superheroes should reflect America—Buddhists, Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims.

I struggled to get that piece published. The only place that would run it was Seattle Times. The editor happened to be an Asian American woman. She connected with that story and published it. Fiona, the photographer, read that piece and emailed me saying she loved the piece and asking if I would reconsider dressing up as Captain America for a photoshoot. This was 9-10 months after our initial conversation about it. I think the tragedy of August 5th allowed me to get out of my own way. I have body image issues. I’d been verbally abused for the last ten years after 9/11. Why would I want to bring more attention to myself? But I said, I’d do it.

VS: She bought me a uniform from Hong Kong and shipped it to me. I put it on at home and I freak out. I bought football and baseball pads, shoved them into my uniform and was looking at myself in the mirror when my wife said, “Vishavjit, this isn’t you! You look like a cartoon! If you’re going to do this photoshoot, this social experiment, you’re going to have to be you. You’re skinny, you have a turban and beard, and that’s what it’s going to be.”

And so these two women in my life—Fiona and my wife—made me comfortable in my own skin. On a beautiful, sunny June day in 2013, I stepped out and did not know what to expect. I was really nervous and thought people might be offended and say things to me. We didn’t know this but it was also the Puerto Rican Day parade that day so people were coming up to me like, “Oh my God! Captain Puerto Rico!” And from there, it just turned into one of the most amazing days of my life. Police officers took photos with me.

I got access to a fire department truck that was managing the parade as a mobile command center. Fiona asked if we could use the truck for the shoot. I got pulled into a wedding. People started following me. Strangers came up and hugged me. I was out for eight or nine hours and didn’t have a single negative experience.

VS: The most powerful moment happened in Central Park, where we started. I was posing and there was a kid on a rock. He was a white middle school kid and after a few minutes, he asked me what I was doing. I told him I was Captain America for the day and he said, “No, you’re not.” I asked why not and he said, “because you’re not white.”

I asked him why he thought I couldn’t be Captain America. He’s a comic superhero! Captain America was created in 1941. Today in the 21st century he could be Black, Hispanic, or Asian. The kid thought for a moment and then said, “Hispanic, yes. Black maybe. But a turban and beard? Absolutely not.”

The thing about this kid was that he wasn’t vicious. He was sweet! He was being honest and reflecting what a lot of Americans are thinking. So I told him “I’m not offended but for the rest of your life, you’re going to have this image of me—skinny with a turban, beard, and glasses as Captain America—and you’ll never be able to get rid of it!” So next time he sees someone with a turban and beard, the image of Captain America might come to mind.

I know that’s a long-winded answer but I wanted to make it clear that this was Fiona’s idea in response to an illustration I had created. It took a life of its own. I ended up writing another op-ed for Salon Magazine and Fiona released six photographs from the series to accompany the article. That piece went viral! I started getting invitations from late night comedy shows, teachers, and organizations to tell my story. That’s how it all started!

VS: It’s a great question. It’s come up at times in my conversations with people. After the first time, after all the invitations, I started donning the uniform again because I felt it opened doors for conversations. Strangers have come up to me and have said, “I’m sorry you have to do this.”

When I wear this uniform, people treat me differently. For the Red, White, and Beard film, we shot for three days and literally on the last day, I went to a Starbucks to take off my uniform. Within five minutes, somebody from across the street yells “Osama Bin Laden.” It’s so jarring that I can be in this uniform and get treated one way but once I’m in civilian clothes, I’m reminded very quickly that I’m not “one of us.”

When I started getting invitations to things like news shows and company diversity events, the invitations that I really felt opened the door for me were with educators. Teachers who were interested in telling diverse stories and focusing on diversity, equity, and inclusion started inviting me to their school. I had a full time job as a techie but I would take time off to travel for these gigs. I started telling my life story of being born in the US, then moving to India as a child, surviving a genocidal massacre, coming back to the US and not being accepted, cutting off my beard and taking off my turban to try to assimilate, and rediscovering my heritage and faith.

I started sharing my story with students—elementary, middle, and high school. One thing that I learned was to be honest and transparent with your vulnerability. Over the years, as I’ve shared the story, I’ve found myself able to talk about the difficult things that we have a hard time discussing like bias, racism, complicit bias, getting bullied, being the bully. I grew up in two cultures—American and Indian—and both have their own flavors of anti-Blackness. I explained how I picked that up as a kid but that I also grew out of it.

But to answer your question, yes. There is an assimilatory aspect to donning the uniform. What I do is I use the power of the story to open doors and welcome people in. As I share that story, I am talking about so many things that we can all relate to. I’ve had kids talk to me about their mental health struggles, challenges of gender bias. To me, that’s humbling! So many of us get targeted for so many different things and those are the connections that hook people into my story.

VS: Sometimes when I go into schools and companies, I’ll ask the participants to tell me what words come to mind when they see me. When I first ask this question, before I share my story, I get “skinny” or “beard” or “that thing on your head” or “somebody different.” But when I ask that question after I’ve shared my story, the words become “cool” or “creative” or “courageous” or “very American.” These are words you wouldn’t use to describe someone unless you knew their story.

Stories are a tool. You can do bad things with them as well as good. Race is a story. Most people don’t think about it that way. My birth certificate from Washington, DC lists my race as white because in the story of race, South Asians are considered Caucasian.

The Captain America story opens a door to talk about racism in America. I thank the creators for creating something that holds so much power, even today.

VS: When 9/11 happened, here in the US, we all united—in good ways but also in ways that we can now talk about. Back then, it was difficult. We came together to honor the lives lost but we also came together in our biases. We adopted this posture of wanting to take this out on our enemies. We knew al-Qaeda and Afghanistan but then we extended it to Iraq which had no connection to 9/11. We justified it as a form of revenge. That was happening on the international front. Domestically, this was taken out of innocent people here in the US.

President Biden was trying to remind and warn President Netanyahu to be mindful and not to make the same mistakes we made. But what have we done to rebuild Afghanistan and Iraq? We failed at those attempts. How do we apologize and seek justice from those who were killed in the name of our “war on terror.” Coming back to the present, what happened on October 7th is not defensible. But look at what’s happened since in the name of fighting terrorism.

Captain America in my mind is someone who is going to push us to have these difficult conversations about whether we are justified in killing innocent people in the name of fighting terrorism. We’ve been here before and it seems that we’re not learning any of those lessons.