The Expansive Vocabulary of Ishita Mili’s IMGE Dance Company

Artist, choreographer, and dancer Ishita Mili believes in the power of hybridizing dance forms to tell honest and globally relevant stories. Over the past several years, the 2023 Jadin Wong Artist of Exceptional Merit has developed a dance vocabulary that incorporates Indian classical, bharatnatyam, Mayurbhanj chhau, contemporary, hip hop, and street styles in a distinct approach to movement that resists hierarchy and codification.

Mili’s refusal to silo these dance forms to their cultural contexts echoes the ethos of egalitarianism and radical inclusion of her dance company, IMGE Dance. Founded in 2017, the company invites dancers from a variety of traditions and styles to collaborate and tell stories about home, belonging, exclusion, conflict, alienation, joy, and growth from an explicitly global and multicultural perspective.

I caught up with Mili this past spring after the spectacular debut performance of (no)man. Split into ten chapters, the constantly evolving multi-modal performance responds to existential, political, and psychological questions, presented as a voiceover at the performance’s opening. In the darkness, the audience is asked: Where do I go when society’s rules change? What do I do when I hate you but I come from you? What do I do when my abilities change? Where do I go when it’s not safe?

“(no)man was developed in the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Mili told me. “Opportunities for performers were few and the questions of inclusion, scarcity, and violence weighed heavily on artists committed to resisting erasure and social oppression.” In response, she invited IMGE’s dancers to share their own individual stories reflecting on their experiences from this time. “The stories that came out probed the relationship between inclusion and exclusion, life and death; the poles of our existence,” said Mili.

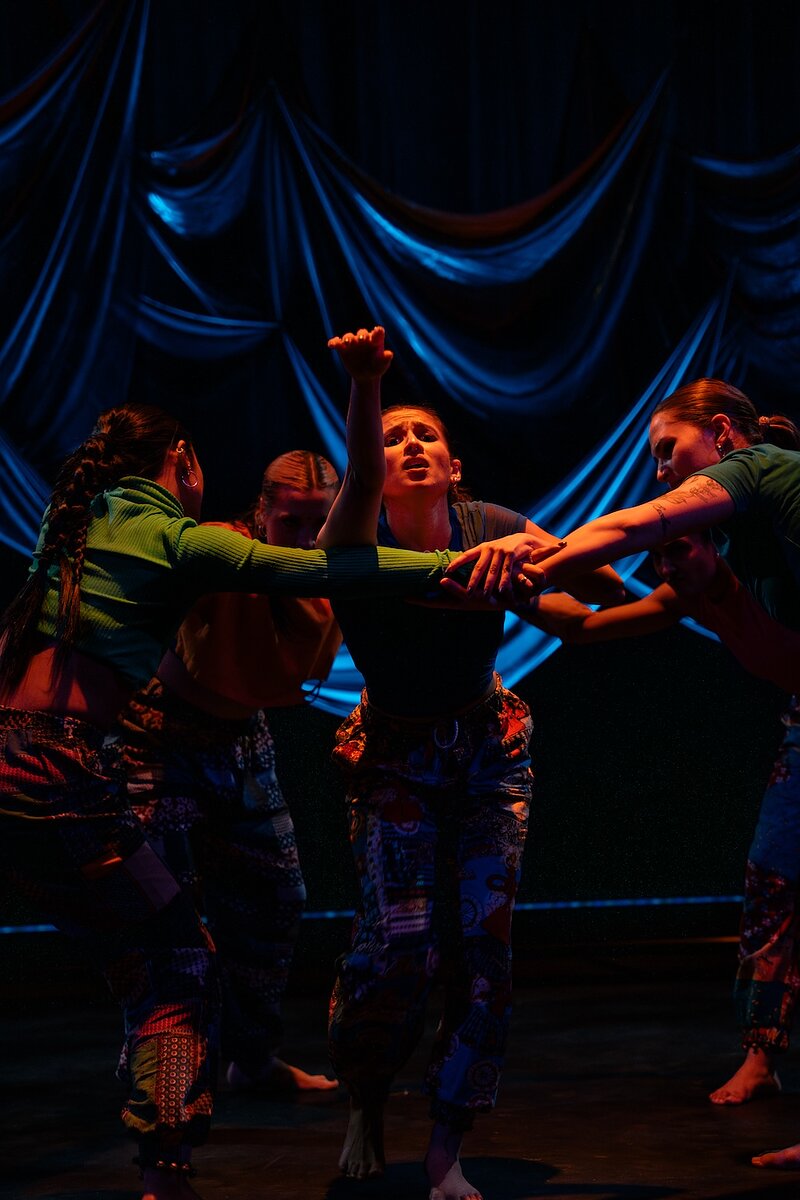

For her, this period of time brought into sharp focus her ideas around identity and belonging. The ten chapters of (no)man revolve around various modalities living together and apart in a fraught present built on contested pasts: (no)mad, (co)habit, (ex)otic, (wo)man, e(man)cipation, (end), (out)cast, (con)vict, (heart)beat, and (no)man’s land. The stories in each chapter are moving portraits of how humans suffer, support one another, fail, and work through failure. Characters show each other compassion, witness one another’s traumas, and pull one another out of literal thunderstorms or from beyond the grip of death to show the weight of a life.

“I love learning about which pieces people connect to,” said Mili. “Which one always surprises me, depending on who I’m talking to.” According to Mili, her own solo performances often resonate with South Asian femmes. In (ex)otic Mili is shown imprisoned. Dancers drag her to the front stage left and bind her hands with chains that come down from the ceiling. At first, she hangs her head, defeated, but then writhes, her face determined. There is no sound but the metal of her chains while her captors celebrate and drink to their power.

Eventually, Mili finds new ways to move despite her captivity, stretching slowly away from the constraints of her imprisonment in increasingly larger concentric circles, nearly reaching her captors who stare and conspire as a single, malicious unit. As she approaches, chains extended, the captors lunge forward but are unable to catch her as she dances with profound strength and grace. She is no longer entrapped by their gaze, their judgment, or their projections but establishing her own vocabulary of being in resistance.

In another piece, (end) Mili maps the range and unpredictable manifestations of grief. Each fellow dancer mourns the death of Mili’s character by enacting scenes that paint a picture of their individual relationship with her. To some she is a hero, others a friend, or someone to laugh with, or with whom things are very complicated. Each dancer combines multiple styles and pantomime, the tension or ease visible in their postures.

“I can’t tell anyone’s story other than mine, and can’t speak for a collective—I truly don’t want to,” said Mili. “It’s more interesting to highlight the individual, inviting people to discover with us instead of preaching.” The jarring specificity of the stories IMGE Dance tells beckon the universal, reminding us that no matter how alone we think we are or how unique our plight, when we listen to and move with one another, we thrive together.

—Ashna Ali is a queer and disabled child of the Bangladeshi diaspora. A poet, editor, educator, and culture activiest, they are the author of The Relativity of Living Well (Bone Bouquet, 2024) and the Substack, PAIN BABY.