Martin Wong’s Bold, Unapologetic Hybridity

When the late artist Martin Wong first self-published Footprints, Poems, and Leaves in 1968, he was just 20 years old. Openly gay, freshly dropped out of UC Berkeley, and experiencing the urban life of San Francisco at the height of the hippie movement, it was during the writing of Footprints that Wong was arrested at a queer, drug-fueled house party, and was, for a time, staying at a mental institution. While bursting with the energy of moving forward and not turning back, Wong’s words are not at all escapist. Rather, they startle with tenderness and a sense of inner resolution:

April 14 1967 / why do you run? / the rain will not / melt you / reflections wont / swallow you / sky will not crush you / night will not touch you / shadows not hide you / sleep not confide you / truth not infect you / dark not protect you / streets not corrupt / your heart not erupt / + I’ll not betray you.

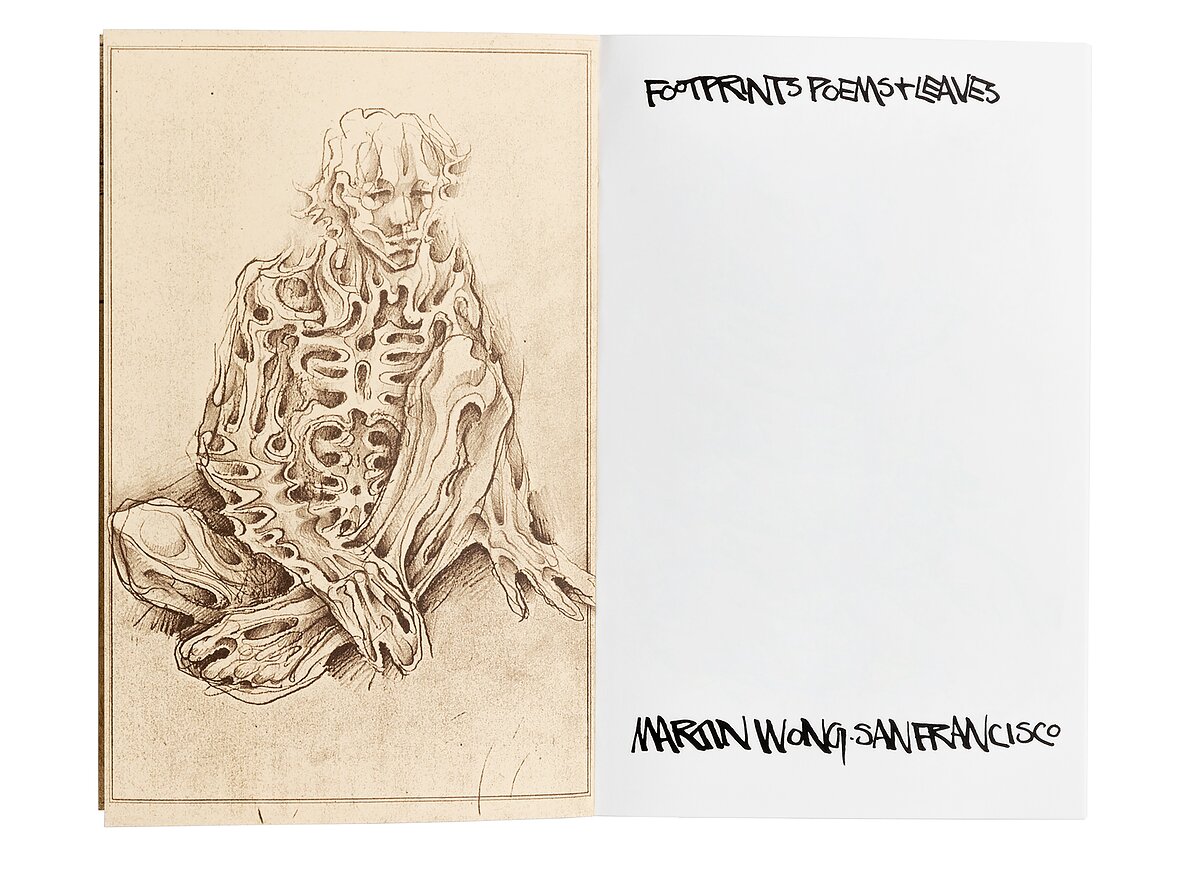

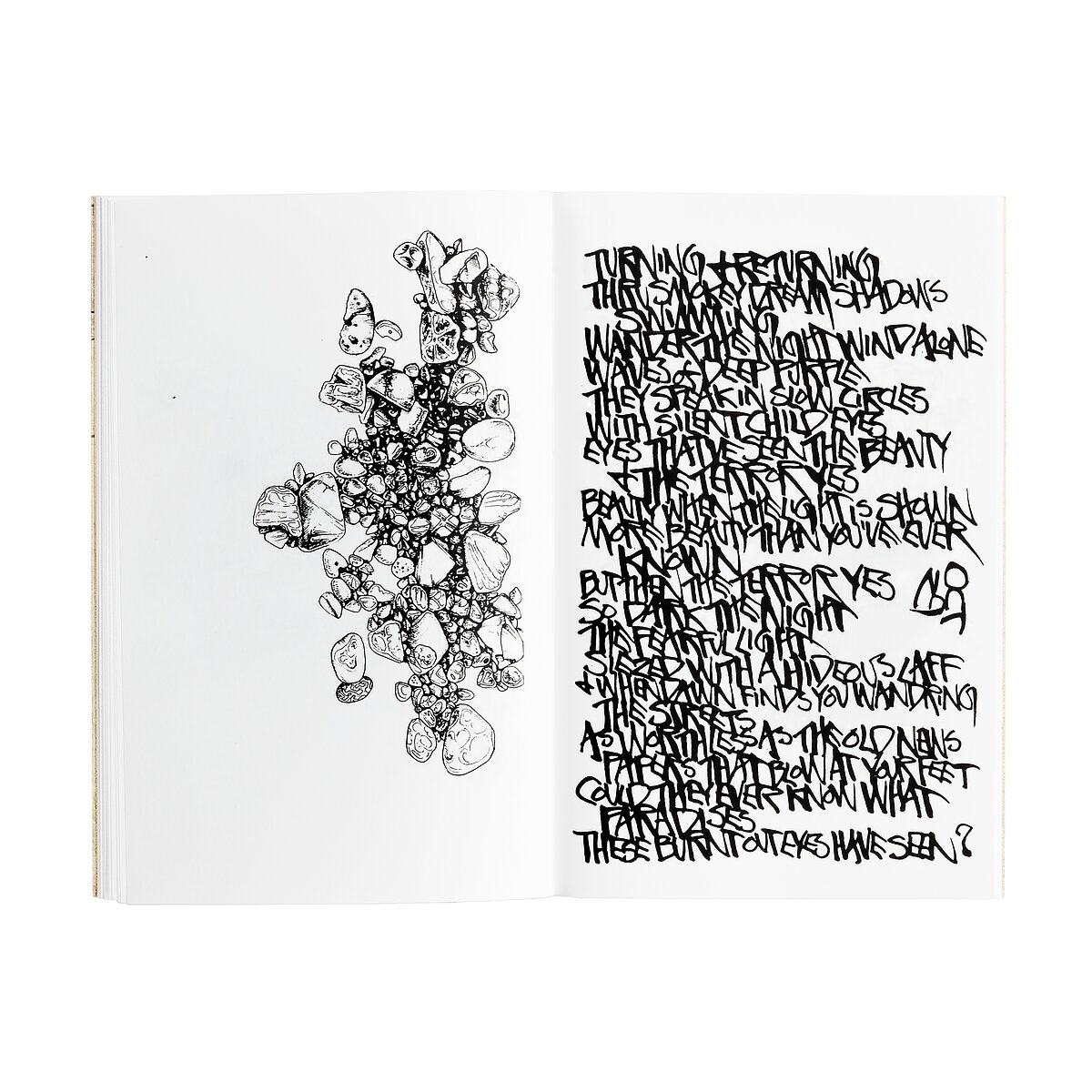

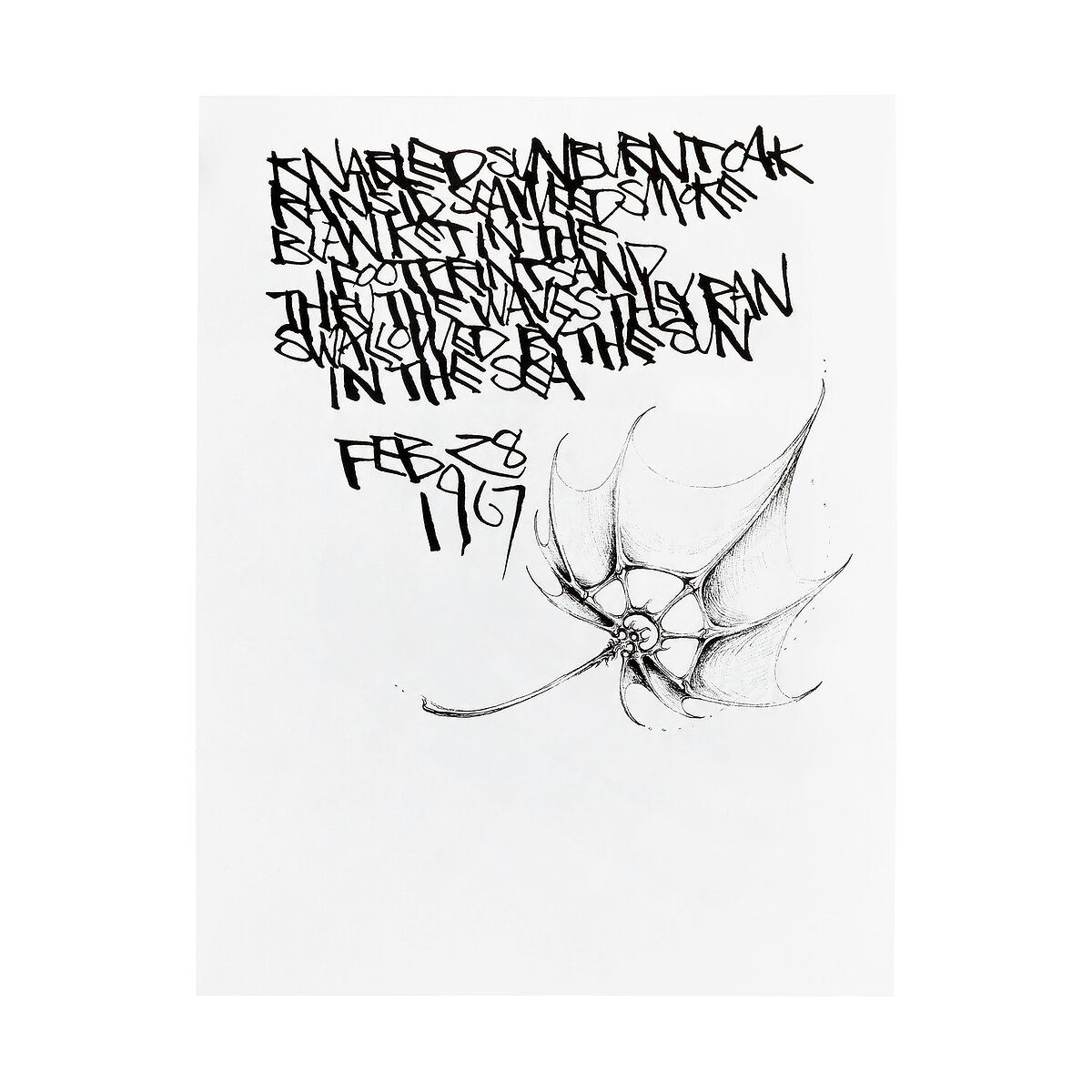

Recently, Footprints, Poems, and Leaves has been released as a facsimile edition by the non-profit organization Primary Information. The slim 68-page volume has the presence of an artist’s journal, hand-written in a developing typographic style that would later become his signature, visible throughout his paintings.

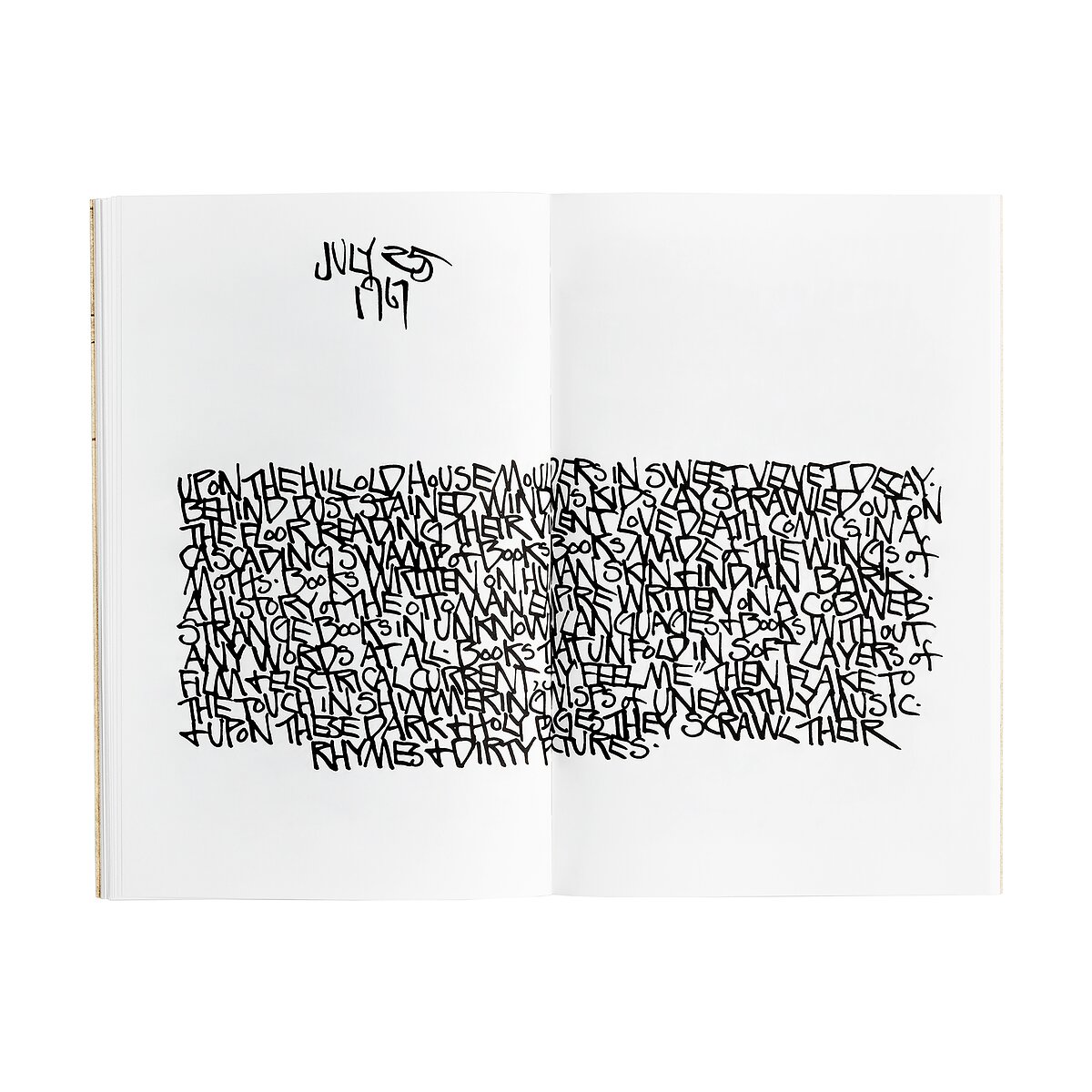

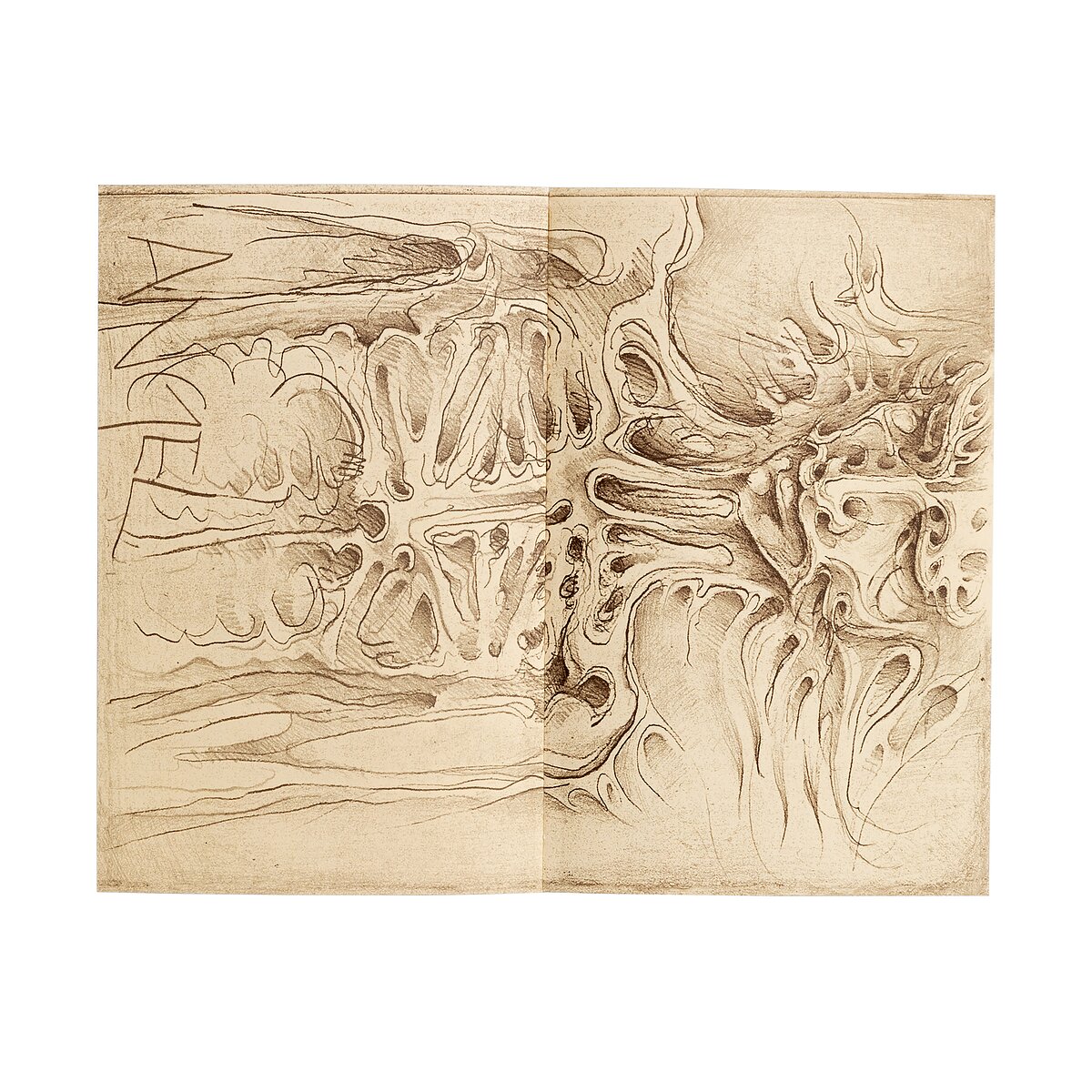

A majority of the inside pages are filled with text alternatingly written with either a calligraphic brush pen, an angled ink pen tip, or marker. These pages are couched between a double cover featuring a drawing of a creature’s face who appears to be in flames—an image that foreshadows references to Asian religious and spiritual imagery in Wong’s paintings—a skeletal figure with the word “Angel” written below, as well as other similarly mystical tableaux.

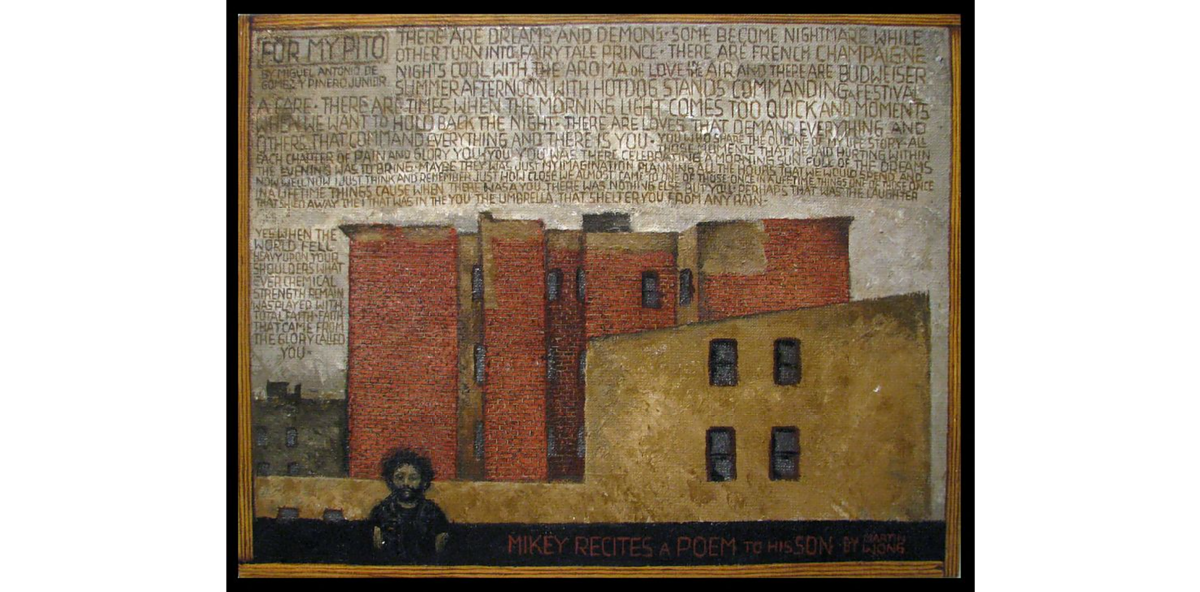

Leafing through the book, I already sensed the same unrelenting intensity and claustrophobia that is palpable in Martin Wong’s paintings. Those feelings were present in an even more unforgiving way given that the function and presence of a book as an object is its innate petition and desire to be read. The words appeared in front of me as a mass or a cluster—the simultaneously angular and drippy capitalized letters bunched together with hardly any negative space in between, the closely knitted words reminiscent of a stack of bricks or links of a chain fence (all images that he later painted).

There is discernible tension where the words seem to want to shield themselves, though this resistant illegibility is a method in which to invite and speak only to the caring reader, one who will make the effort to decipher it. Like the graffiti that Wong revered and would later go onto collect in his years in downtown New York, the text in Footprints sprawls across the pages with the same riotous yet deserving spirit—restless, overflowing, tumultuous, and full of possibility.

After self-publishing Footprints, Wong enrolled at Humboldt State University to finish his degree in ceramics. He abandoned the medium as soon as he was barred from showing work that used glitter for a competitive ceramics exhibition that he won at the de Young museum in San Francisco in 1970. While many describe Wong as being self-taught as an artist, his training as a ceramicist makes this categorization inapt and even misleading; it is quite common for visual artists to explore different media throughout their career.

Born only three years after the repeal of The Chinese Exclusion Act and having died at the young age of 53 due to AIDS related illness in 1999, there is a tendency to place Wong on the outside—whether on account of his race, sexuality, or his relationship to institutions and dominant art movements. It is therefore far more accurate to describe Wong within the context of hybridity, evinced as early as in Footprints and carried through the rest of his life. Martin Wong understood and recognized definitions and categories, but there was in him a persistent, unyielding force that wanted nothing but to keep slipping away, free of them.

Jan 23 1968 / Space warp hypo fugitive / ready on the run / ace of spades ten of clubs / the fix is on: / pulse neon down the / midnight highway/ as the desert night hums by / radio blink vinyl songs / so sleek / next to me my lover sleeps / yesterday had nothing / till just then / + might still have nothing / come tomorrow again

—Diana Seo Hyung Lee is a New York based writer and translator. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, The Brooklyn Rail, Frieze, Momus, The Amp, Hyperallergic, and others. She is an immigrant, born in Seoul, South Korea, raised in Queens, New York, and is a mother of a five year old called Mark.