“Magazine Fever” Lays Out the Cycles of AAPI Identity

Every few years, a newly launched Asian American magazine will come across my path. Whether a glossy lifestyle mag or a more literary-minded journal, its name will inevitably consist of a pun or wordplay intended to reclaim a stereotype associated with Asian identity. If any self-deprecation seeps through my tone, it likely has to do with personal memories of editing my college’s Asian American student publication. While ours was nowhere near as professional or sophisticated as these more recent platforms, whether print or digital, many of the concerns remain the same: how to tell our stories and represent ourselves.

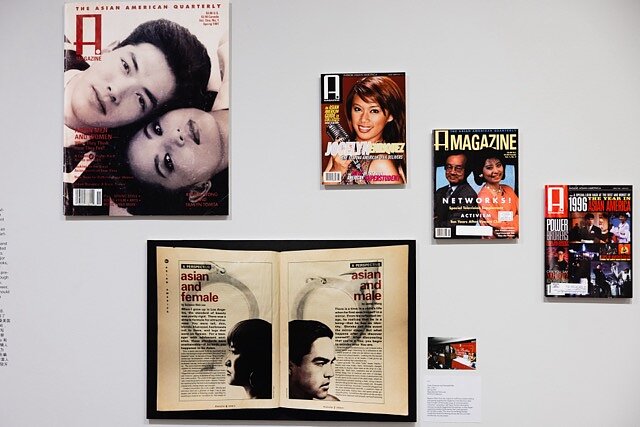

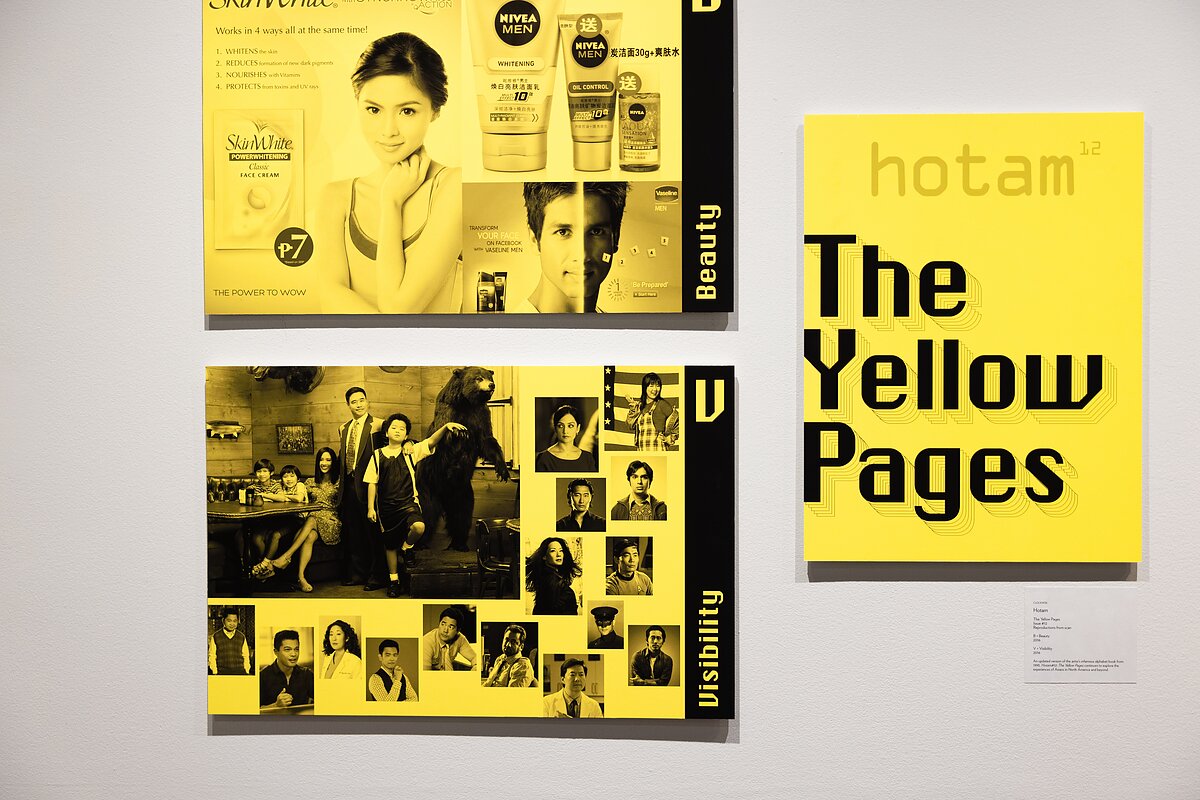

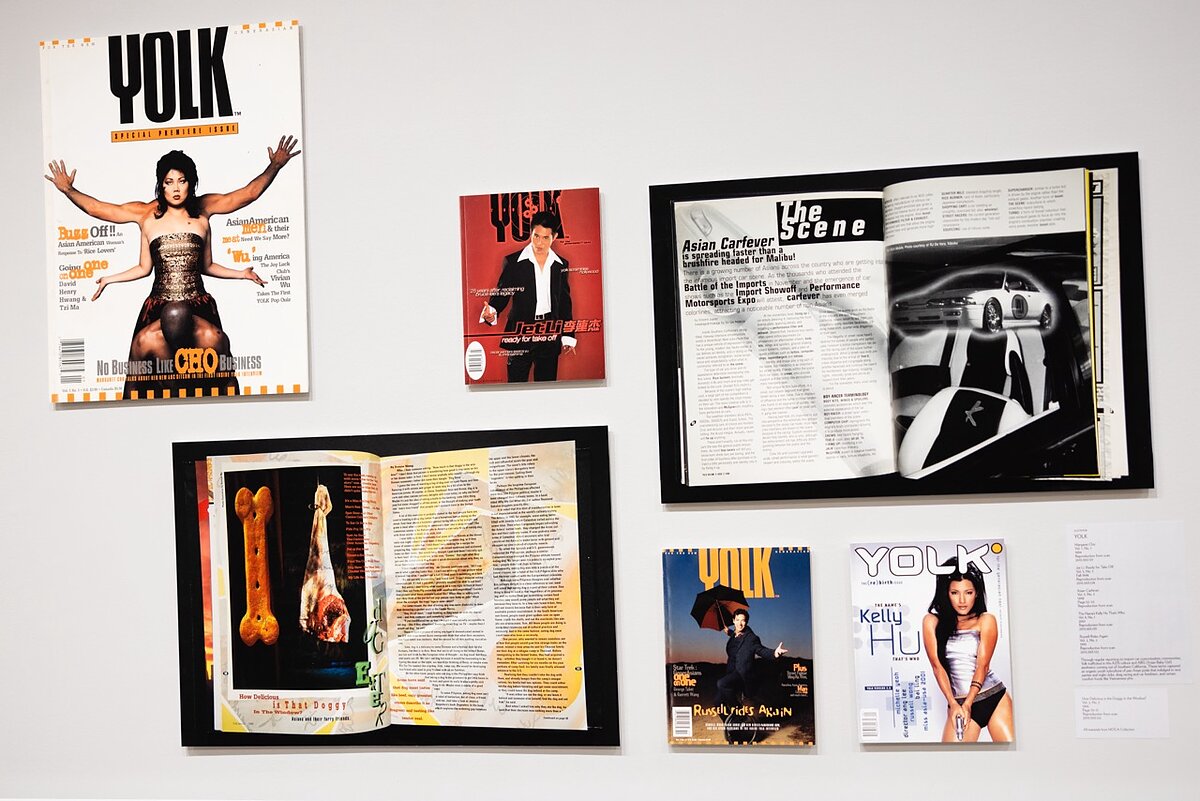

Standing inside “Magazine Fever: Gen X Asian American Periodicals” at New York’s Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA), and gazing at the dozens of magazines on display, I saw that it had indeed all been done before. Among those that published primarily in the 1980s and ‘90s were A. Magazine, AsiAm, Transpacific, Jade, Rice, and Yolk. I was especially tickled by a case containing other inventive titles such as Monolid, Hues, Colors, invAsian, Bamboo Girl, and Oriental Whatever. It should be noted that the collection largely focused on magazines founded by editors of East Asian descent.

A slew of reprinted covers from every major US outlet of the era papers the far gallery wall, not only anchoring the space visually but also providing the raison d’être for the museum’s survey. Not a single one features an Asian face, with the exception of a 1987 issue of TIME, in which a group of nerdy-looking students are characterized by the header as “Those Asian-American Whiz Kids.”

Here is the source of the wound, the exhibition suggests. It tracks, then, that in order to combat both a glaring lack of representation and undesirable stereotyping, Asian American Gen Xers reacted by plastering their media with the most famous Hollywood actors they had at the time—John Cho, Lucy Liu, Sandra Oh, and even Dean Cain, with Margaret Cho sweeping them all with no less than three cover appearances by my count. As stated in MOCA’s press release, “Magazines were the ideal forum for this generation of Asian Americans to express and celebrate their versions of cool, beauty and success.”

Carrying the torch into the new millennium, magazines like Giant Robot offered a punk alternative, while Hyphen took a quirkier approach. I began reading the latter in my early 20s, drawn to their coverage of books by writers like Ted Chiang, Katie Kitamura, Cathy Hong Park, and Charles Yu. Founding editor in chief Melissa Hung pointed out that Hyphen was one of the few Asian American magazines led by women. Over Zoom, she recounted the publication’s origin story, how it emerged out of the dot-com crash of the early 2000s, dreamed up by a group of friends in the Bay Area who had been laid off from their magazine jobs.

“We wanted to do investigative reporting. We wanted to dig deeper. We were interested in people who were in arts and culture, who were not the few anointed by the mainstream, who were doing something interesting,” Hung said, in response to my question about what gaps Hyphen hoped to fill for its readers. “We wanted to be a progressive Asian American voice. I think that was what helped set us apart.”

The importance—and challenges—of engaging Asian Americans politically was on both our minds when we spoke, just two days after the 2024 presidential election. This push and pull revealed the cyclical, sometimes seemingly amnesiac, nature of Asian American political alignment that each generation always seems to be experiencing. Lest we forget our activist roots, “Magazine Fever” paid homage to the Asian American Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, highlighting foundational materials like pamphlets and zines that laid the groundwork. According to the wall text, the Japanese American students at UCLA who started Gidra in 1969 explicitly saw their identity reborn as “one who will recognize and deal with injustice.” It was a little jarring to see the ethos of this DIY newspaper critiquing the system of capitalism for perpetuating racism give way two decades later to the mass-produced glossy Rice hailing “Asians in Silicon Valley,” displayed along the same gallery wall.

Have we really moved so far from the radical left to the neoliberal center? Or have we always been a messy patchwork of competing goals? The limits of representational politics is playing out at this very moment in local organizing against MOCA, which itself has been accused of “actively harming Chinatown’s residents and economy.” As we’ve come to learn, shared identity doesn’t necessarily translate to a shared vision of community.

Looking back on her time at Hyphen, Hung said, “Solidarity within Asian Americans, and also with other groups, was something that we thought a lot about.” In retrospect, she wished those collaborations “could have been strengthened, and in a way that felt more real and lasting.”

As a millennial, I wonder about the legacy our generation inherited. Out of curiosity, I dug up an old print copy of my undergraduate publication, titled appropriately enough, Generasian. The fall of my senior year at NYU, we published a themed issue, “Outside the Box.” I flipped through the black-and-white pages to a profile about Grace Meng, a then rising star in Flushing politics; another article bearing witness to a shrinking Chinatown in the aftermath of 9/11; and a review of a documentary defending Native Hawaiian rights. I was surprised how earnestly my fellow writers—friends and classmates—sought to elucidate these issues for our readers, who were in reality ourselves. In my Letter from the Editor, I had written, “Only by looking at different parts can we begin to understand the whole. Maybe what we will come to find is that there is no definable whole to speak of.”

Thinking about the wall of magazine covers and the absence of Asian Americans, I see not something to aspire to but rather a reminder to resist flattening our identities for the crumbs of acceptance, to reject conformity. Crystal Parikh, a professor of Asian American literature and studies at NYU (and a teacher I was lucky enough to learn from when I was a student), embraces the notion of a “minority” perspective, which “allows us to interrogate what we take for granted as good and desirable.” Even as Asian Americans accrue more cultural, economic, and political influence, Parikh underscores the value of retaining a critical point of view: “we will be able to continue to probe who wields power, how, and why, while also according recognition to and seeking justice for those other ways of life that exist beyond the norm or the majority.”

When I scroll through the current iteration of Generasian (now a website and no longer a printed magazine), I see Gen Zers writing for themselves, in the same way my peers and I at the time sought to make sense of the world around us, tested out our ideas without worrying about the white gaze, and spoke directly to each other. “I think there is still a need for our own space, where we can have the conversation among ourselves,” Hung insisted, especially in light of the election.

Maybe we are doomed to repeat the same discourse over and over again, or maybe that just means the project that began with the Asian American Movement is not yet done. As the front page of Gidra proclaimed, “We will fight and fight from this generation to the next…”

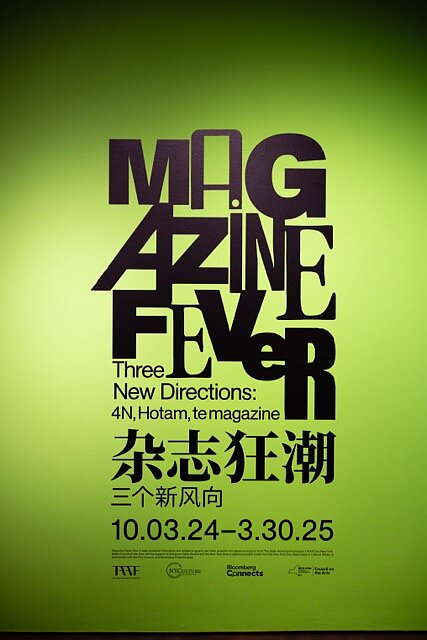

—"Magazine Fever: Gen X Asian American Periodicals" is on view at the Museum of Chinese in America through March 30, 2025.

—Mimi Wong is a writer based in New York. For her work engaging with contemporary art by artists from the Asian diaspora, she was awarded the Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. She is Editor-in-Chief of the literary magazine The Offing and a part-time lecturer at Parsons School of Design.