“Here Lies Love” is a Troubling, if Entertaining, Take on Filipino History

Blue and pink lights rove across the dancefloor and rotating runway stages. A DJ’s voice punctures the cool, crisp, air conditioned air with a warm welcome to Club Manila, as David Byrne and Fatboy Slim’s Broadway production of Here Lies Love commences. Originally written in 2014, the musical brings audiences into the modern history of the Philippines by following the rise and fall of Imelda Marcos, former first lady to the dictator Ferdinand Marcos—all set to a karaoke-style disco soundtrack. Together, the couple infamously accrued an estimated $10 billion and were responsible for the deaths of thousands while in office before being ousted by the People Power Revolution in 1986.

In a nation where 51% of the population still considers themselves to be poor, the legacy of the Marcos regime has cast a long, complicated, and traumatic shadow for many. The timing of the show is compelling given that Imelda and Ferdinand’s son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., clenched the presidential bid in 2022 with the support of Cambridge Analytica, the same data company that helped deliver the Trump presidency. Here Lies Love offers a tendentious glimpse into the complexities of the Filipino struggle for democracy by centering its most infamous first lady and her descent into corruption.

The script paraphrases and arranges Imelda’s real quotes into lyrics, creating a bare-faced critique of her philosophy and exploitation of poverty—the show’s title is taken from a 1987 interview in which Imelda and Ferdinand are asked what they’d like their epitaph to read: “One word,” said Imelda, “Love.” By also citing the U.S. support of the Marcos regime (Reagan’s administration helicoptered them to Hawaii after they were expelled) the show bemoans the ongoing normalization of U.S. interference in the Philippines.

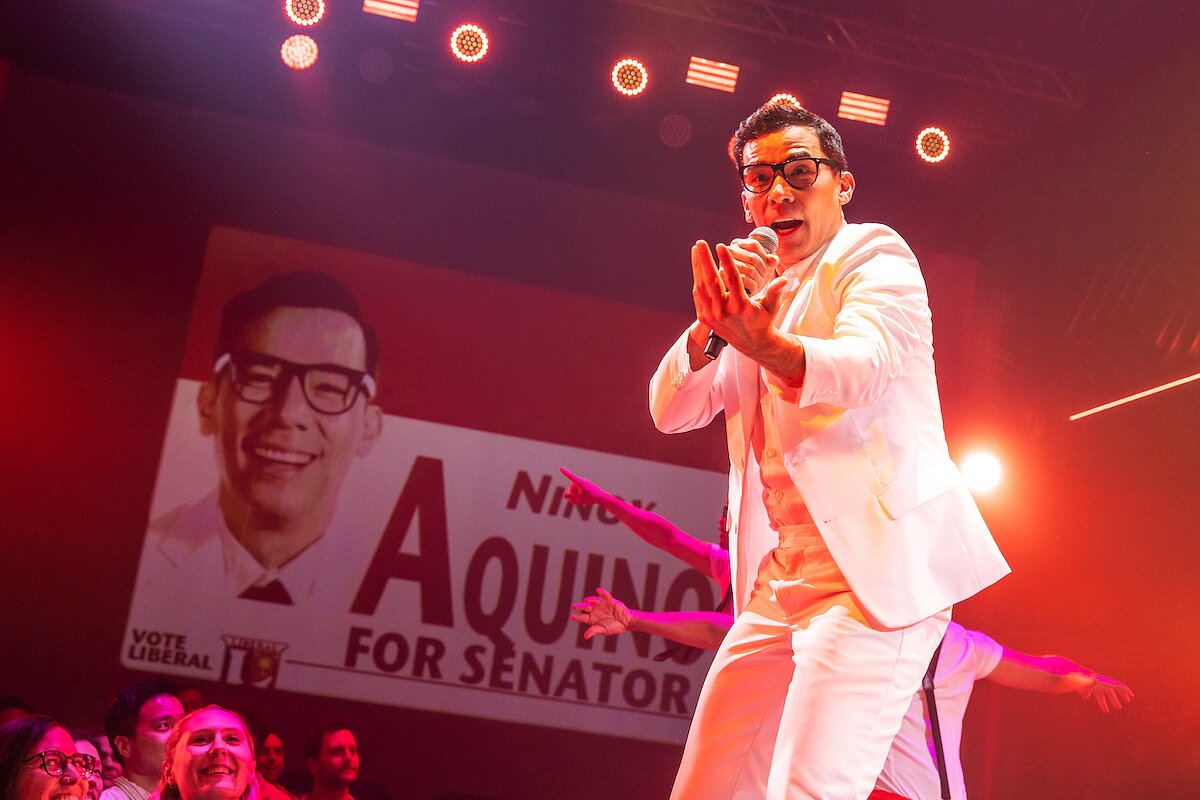

The historic all-Filipino cast is a powerhouse, especially the corps ensemble. Conrad Nicamura’s interpretation of senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, the Marcos’s foremost opposition leader, grounds viewers against an otherwise dark history. Imelda, played by Arielle Jacobs, may be the main character, but Ninoy is the show’s hero as the only voice calling for democracy and disrupting the couple’s ascent to power.

Lea Salonga, playing Aquino’s mother, sings a gripping lament after his assassination that poignantly juxtaposes Imelda’s repeated lines “it takes a woman to do a man’s job,” which may reflect commonly held suspicions that Imelda ordered Aquino’s death. There are, however, questionable, perhaps even inflammatory historical inaccuracies in the staging, particularly when it comes to the centering of a lifelong romance between Imelda and Ninoy—a rumor that progressive Filipino news outlet Rappler, founded by Nobel prize laureate Maria Ressa, squarely denies.

While the show succinctly highlights Imelda’s cruelty, the hour and a half time constraint reduces the topic’s complexities. The People Power Revolution is reduced to a procession of protest effigies in the dark on the far end of the dancefloor from Imelda, who pleads in the spotlight, “why don’t you love me?” A brief scene of police brutality and flashing headlines reveal some of the Marcos’s most heinous abuses: 3,200 killed; 34,000 tortured; and over 70,000 imprisoned. Still, the show ends with a powerful ensemble protest song representing the movement, its chorus declaring: “God draws straight, but with crooked lines.”

Consistent interweaving might have offered more equitable representation between the 1% and commonfolk. The erasure of Indigenous Lumad and the leadership of women in the resistance must also be considered. The former becomes more apparent when one notes how few dark-skinned Filipinos were cast.

Centering the perpetrator of violence and not the survivors risks alienating many Filipinos who were omitted from this history. The Here Lies Love website does take educational responsibility by including a timeline of events, starting with Spanish colonization and U.S. imperialism, as well as resources for additional historical research. All in all, this production exposes the need for more Filipino stories written by Filipinos that center the survivors of the continuous impact of the Marcos family. For those unaware of the ongoing political crisis, further research is recommended (Ramona Diaz’s documentary, IMELDA, is a good place to start). What all might appreciate is that the production is historic for representation in this country and depicts the havoc wrought by the United States’ interference in the Philippines.

—Rohan Zhou-Lee, pronouns They/Siya/祂/Elle, is a dancer, writer, and public speaker. They are also known for founding The Blasian March, a Black-Asian solidarity initiative through education and celebration.