Chang Yuchen on Love, Loss, and the Mediated Self

Artist Chang Yuchen’s husband Yuan Yi passed away suddenly in 2014. In the months that followed, she opened his hard drives to discover, amongst his own oeuvre of films and photographs, a vast archive of screenshots and videos documenting their long distance relationship, sustained between 2011 and 2013 over the Chinese messaging and video chat software QQ—he from Beijing, she from Chicago and New York. Returning to these documents almost a decade later, Chang’s two-channel video installation For those who share mornings and evenings (2025), presented at Smack Mellon last fall, presents an ambivalent portrait of presence, capture, collaboration, and longing through media.

Collaboration often pushes us to uncomfortable places, forcing us to inhabit new concepts, shapes, and methodologies. To complete Yuan’s work, Chang stepped into his medium—that of durational film—departing from her customary formats of drawings, artist’s books, and functional goods produced under the moniker Use Value. (Chang’s gauzy, handmade aprons can be seen currently in the exhibition, “The Endless Garment: Atlantic Basin” at Pioneer Works through April 12, 2026).

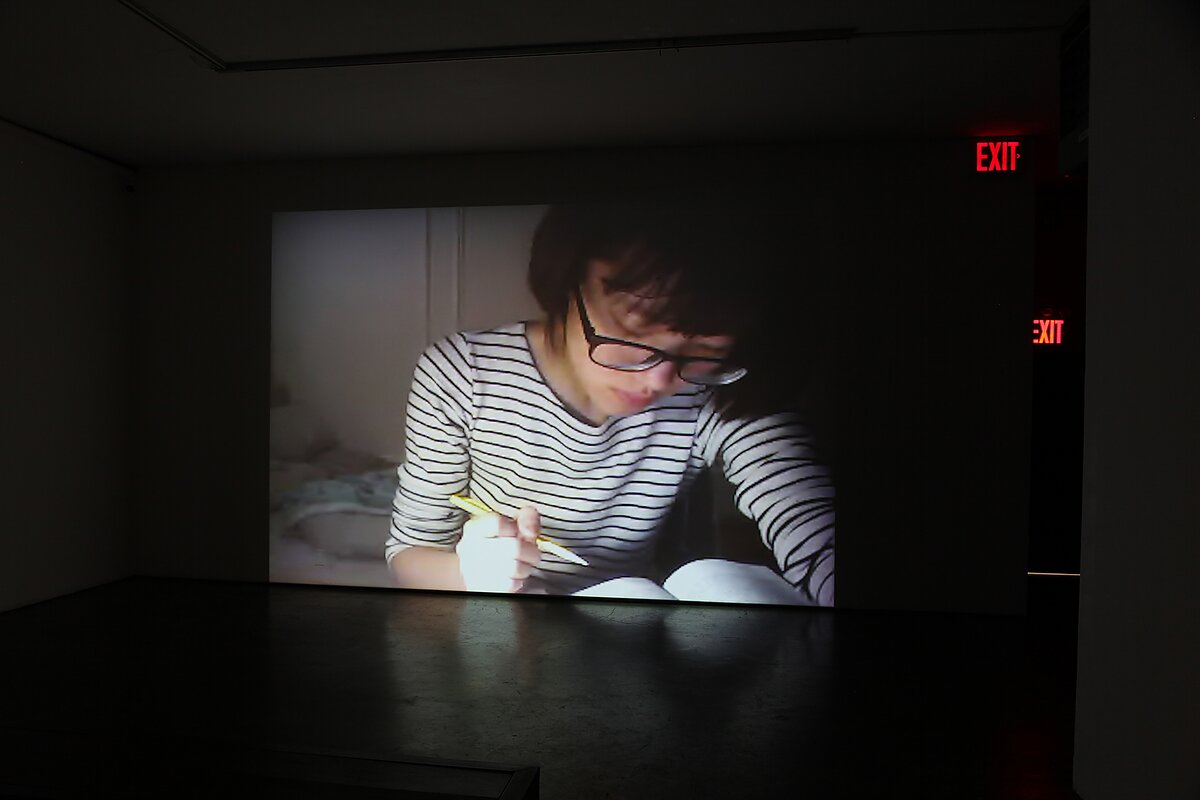

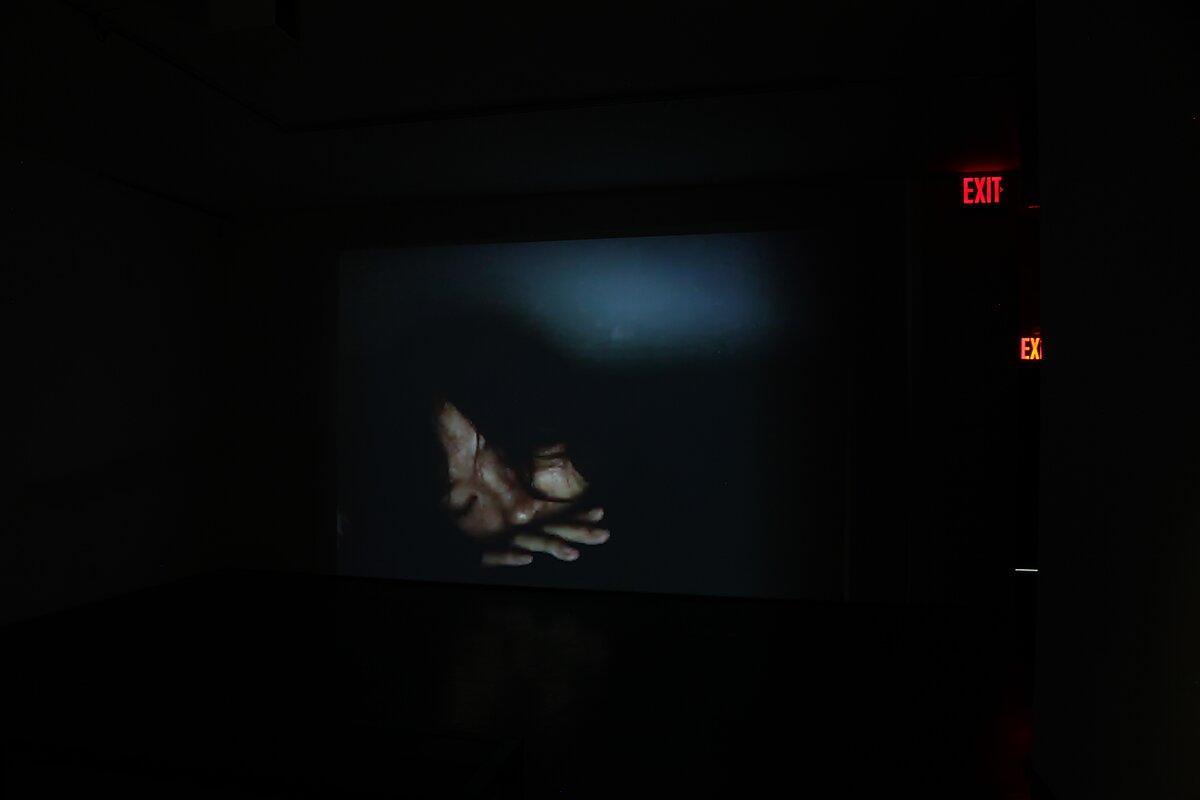

Low resolution from poor connectivity occludes Chang’s features in For those who share mornings and evenings, presented as a wall-scale video. Animated in thousands of screenshots taken by Yuan during their video calls, Chang’s figure is fleeting, the frame rate driving and preemptive. She is a flicker-film of sudden, jerky gestures: she tilts her forehead toward the camera, deadpan; brushes her cropped hair behind an ear; a hand darts up to hide her laughing mouth; slender fingers flash a piece of paper at the camera and drop it before we can begin to read. Though it is the watcher, Yuan, who is now gone, there is a sense that it is Chang who is in the process of vanishing, pixels dissipating in grainy coronas of light. Thematizing the exchange of gazes—watching another, being watched—the video’s circuit is completed by the entrée of viewers, Yuan’s unwitting surrogates.

Chang and I have known each other for many years. When I could not see the installation in person, she shared MP4 files of the work, which I screened in absentia, recreating the context in which the original frames were taken. Adhering to this digital framework, Chang and I met in a video call to discuss intimacy in virtuality, affective mediation, and attempts at tactility in the ether.

Chang Yuchen: In 2015, I tried to make a website to preserve and display this database; they were produced on a personal computer via the internet, so I felt that’s the way they should be viewed. But I didn’t really know how to build a website, and very soon the images were too many for the web page to load. I stopped there.

I returned to it when Rachel Vera Steinberg invited me to work with the gallery at Smack Mellon. For those who share mornings and evenings was conceived with this space in mind. Projection is natural in that room; there’s no window, and it’s in the back of the gallery, in this secretive space, very intimate. I wanted to use projection, because it is not real; when the machine is turned off, nothing is there. I didn’t think too much about scale; they turned it on, it was that big. The screenshots are so ordinary and lo-fi. To have them enlarged to such a non-human and monumental size—I enjoyed the absurdity.

The video has a soundtrack that I made with a recording from the same period of time when the screenshots were taken, when I was in grad school in Chicago and thought I would be a sound artist. I made a contact mic by hand and recorded my breath with it taped to my mouth. As I was going through old hard drives, I rediscovered that recording and thought it would be a fitting accompaniment. I looped it with a hard trim so that it cuts in the process of exhaling. I felt that the hard edge made sense in this piece because the screenshots are, like the audio, sliced from the continuity of time.

CY: When I first encountered the screenshots in their entirety in 2014, I could sense from the quantity that they were footage. This seemingly obsessive, hoard-like collection is, in fact, methodical and stylistic. He had something like a project in mind. If taking them was an act of affection or longing, I think ten would have been enough. But to militantly and at an increasing rate generate images? He took eight thousand screenshots during one conversation in 2013. The rate of capture got so fast that many images were identical. I thinned out some folders before importing them into the animation sequence, because otherwise my image would be moving slower than real time.

I have had doubts about whether this work is art—whether it is appropriate to frame this project that way. Because it is rather personal, I could be clouded, driven by emotion. But my intuition as an artist tells me that it is an incredible archive—very strange, very mundane, very greedy, very devoted, very ambitious.

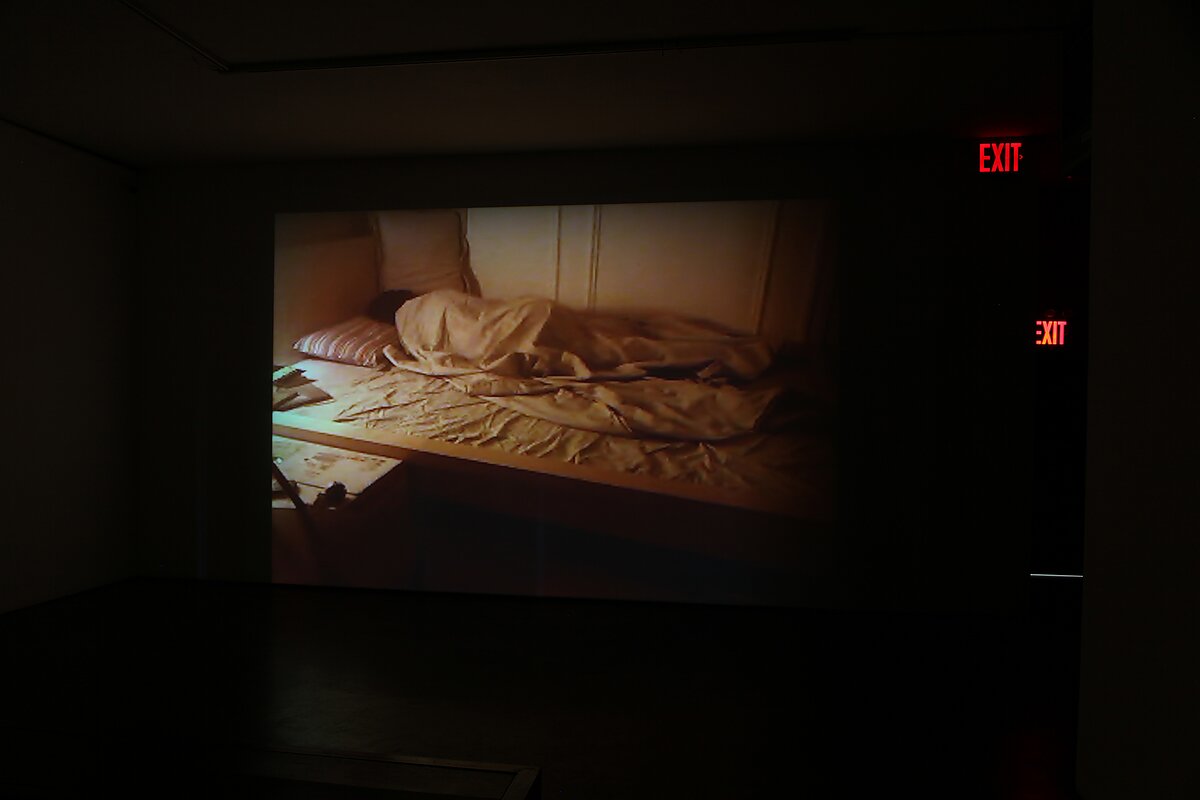

CY: That’s an interesting point, I’ve never thought of it that way. It’s true: Yuan Yi turned moving images into still images. Our time together was captured, objectified, reified. A process turned into a thing, hence touchable. I’m not sure if he was conscious of that. By a twist of fate, the still images fell back into my hands, and, in [the] presentation at Smack Mellon, I animated them back into moving images—untouchable again. In presenting this archive as a video, I wished to infuse the images with an ephemeral lightness. This ghostly medium feels appropriate given the weightiness and massive scale of the archive.

People used to believe that photography steals your soul. I don’t know if that’s true; it could be. After the composer Ryuichi Sakamoto passed away, I went to a virtual performance called Kagami that he created before his death. He was captured in mixed-reality, playing piano. I felt torn and pained; my tears kept falling, fogging the lenses of the heavy headset. My body, my eyes, even my brain told me he was there. But he was not. That contrast is very cruel. It’s the same feeling as right now—we are chatting, and we feel really connected, but when the conversation ends, and I hit the red button, I will be alone in this room. I think that’s really perplexing. I think there’s cruelty embedded in mediated presence and documents that persist even when the body is gone.

I’m not sure if Yuan Yi’s screenshots peeled my soul from me. Our story is a bit different, because he captured my image, yet, he’s the one who disappeared.

CY: There were times leading up to the show that I didn’t want to include Ten Nights of Dreams anymore. I worried the text would anchor and limit the image. Later, after the show had opened, a friend reflected that by adding a second video to the show a third element entered the installation: death. I realized that perhaps that’s why I resisted it. Without Ten Nights of Dreams, the show could just be about love.

Seeing them inhabiting the gallery together, corresponding diagonally across the viewing bench, I’ve developed a new understanding of their entanglement: a long-distance relationship is like a dream. The loved one only comes to you late at night. You can see and talk to them, but you can’t touch them. If so, then having dreams is also a long-distance relationship; those dreams I had were actually a continuation of my relationship with Yuan Yi. It’s a “cosmotechnics,” a medium for communicating that existed long before video chat became possible.

CY: In that dream, I could time travel by drinking a brown medicine and holding a digital camera in my hand while thinking about the year I wanted to visit. I first went back to 2012, and Yuan Yi was a bit cold with me. So I went next to 2014, because he loved me more then. I suppose you are suggesting that the making of this video is a bit like that dream. Except that, facing Adobe Premiere Pro in my studio, I can’t interact with people from the past, unlike in dreams.

Another aspect of this time travel is that, in returning to the hard drive, I also returned to images of myself from 12 to 14 years ago, a self that feels really distant and strange. Strange because I was so young then, and because I’m not just gazing at my delayed reflection in a pond, I’m gazing at how I was once gazed at. Maybe love always comes with estrangement, alongside unity. A passage from Jean Luc-Nancy’s The Inoperative Community might be of use: “As soon as there is love, there is this ontological fissure that cuts across and that disconnects the element of subject-proper…it disjoins me.”

CY: I don’t think I am very collaborative. I’m very lucky to be gifted with or to have access to my mother’s drawings, for example, or Yuan Yi’s hard drive. But the processes of my projects are solitary, autonomous. I’m not working with my mother or Yuan Yi, but for them or after them. Maybe it’s more accurate to call these projects a form of dedication.

When I first conceived of this work, I reached out to Yuan Yi’s mom. She pointed out that this is something very aligned with his aesthetics. After the opening, I found three very short videos that Yuan Yi made. With his Nokia, he had filmed the act of clicking through the screenshots. They were handmade animations. I must have seen them before—I went through all his photos and videos so many times—but I had forgotten. So it turned out that my execution was quite close to what he had intended.