Carlos Villa and Leo Valledor, Reunited

Carlos Villa and Leo Valledor were born 11 months apart in 1936 (Leo was older), and their mothers were from the same village in the Philippines. They both grew up in low-income neighborhoods of San Francisco’s Tenderloin and Fillmore districts (Villa in the former, Valledor in the latter). Practically knowing each other since birth, despite not being related by blood, they referred to each other endearingly as cousins. Currently, both artist’s works are being shown side by side for the first time in “Carlos Villa and Leo Valledor: Remains of Surface" at Silverlens’s New York gallery (up through November 4th).

Their early bond and that Valledor encouraged Villa to attend art school may cause one to wonder why the two did not show together more. Though there were convergences in their careers—they each spent time in New York in the ‘60s and taught at the California Institute of Art—their works took on different formal and conceptual concerns. While Villa is widely recognized for engaging with cross-cultural identities and indigeneity, Valledor is remembered for his minimal, color field paintings.

The show is comprised of works from the late ‘70s and mid ‘80s that Villa and Valledor made upon returning to the West Coast after their respective sojourns in New York. For Villa, these pieces represent a developed but still early part of his oeuvre, since he lived until 2013, but for Valledor, the show reflects his mature works, having passed away in 1989 at just 53. Curated with close input from the estates of Villa and Valledor (both of which are currently managed by Mary Valledor with Leo’s son and Carlos’s stepson, Rio Rocket Valledor), the works chosen seem to amplify the artists’s overlaps and articulate their differences with nuance.

Leo Valledor’s Between Heaven and Earth (1973), a monumental painting composed of a salmon-coral triangular canvas with a golden square on its right, couched between a silver semi circle canvas and a white semi circle canvas in reverse at opposite sides, opens the exhibition. Far from a stark and unfeeling display of geometry, the work is rather a spiritual conjuring. Even with the flatness of the acrylic paint risking a kitsch, pop appearance, the warm coral reads as tender and organic like sun-kissed skin. The metallic next to it, by association, becomes a golden heat.

Valledor’s The Blessing (For Rio) (1970) evokes a solar eclipse in reverse. Painted for his son Rio a year after his birth, the work consists of a large circular canvas of silver, layered over with a white circle almost but not large enough to reach the edge of the canvas, leaving a thin rim. While reminiscent of a portal or a passageway, it remains a painting and not an illusory device—streaks of white paint from the inner circle drip downward, mucking up the boundary between the white and silver. If one felt transported by Valledor’s portal, he would insist that it be accomplished by the painting, rather than by leading the viewer to an elsewhere.

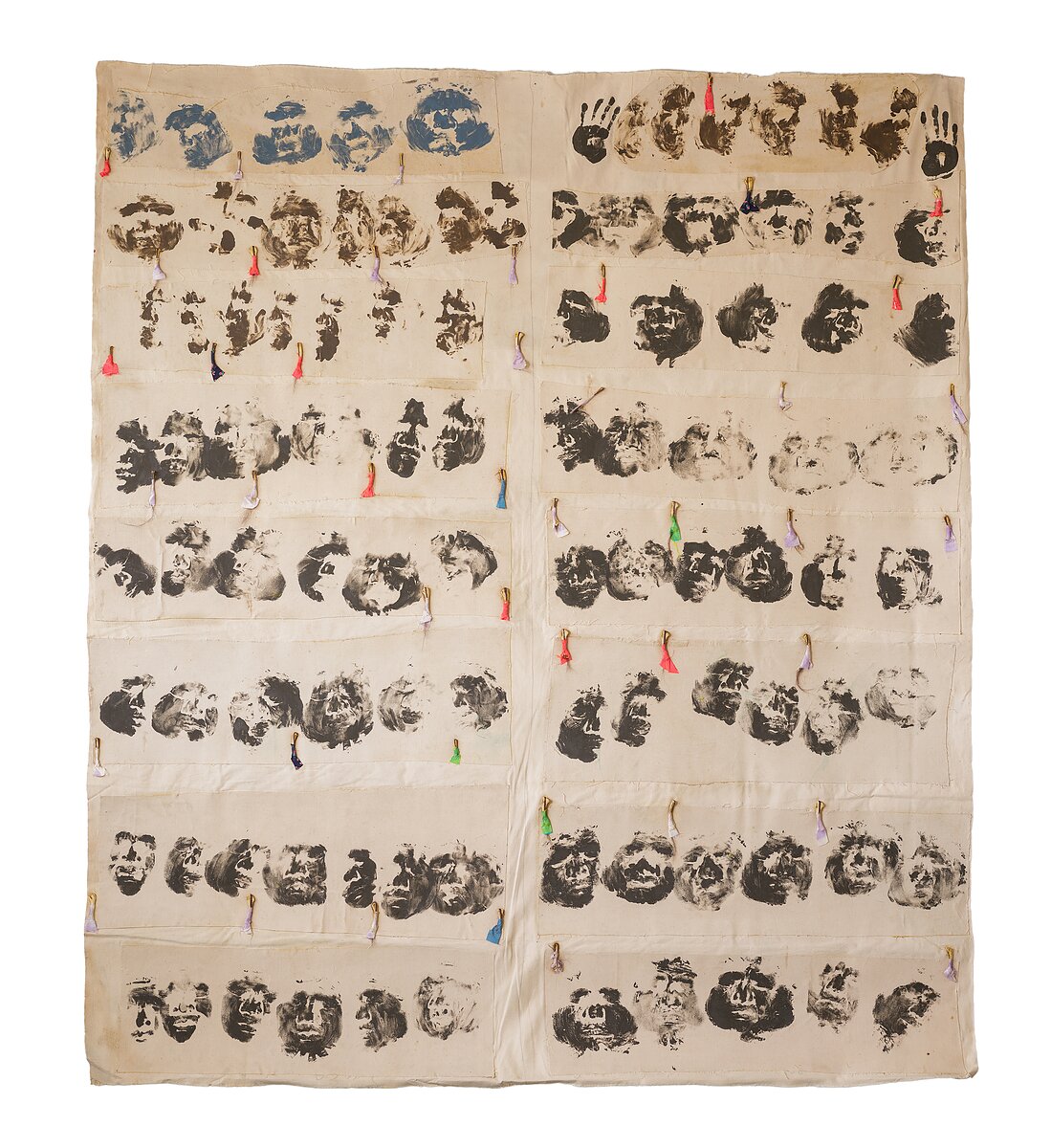

As for Carlos Villa, on view primarily are his large unstretched canvases featuring collaged elements and his signature face and foot prints, sometimes accompanied by hair, bones, etc., such as Untitled (Face Prints)(c. 1979-1982). The act of an artist using his own face as a stamp brings up ideas of ritual, suggesting something otherworldly, shamanic even. At the same time, this action is presented in a linear, grid-like repetition. Unlike Valledor who spills out of the color field, Villa’s body leaps around, but it does so while drawing attention to the borders and constraints of the canvas, suggesting that true freedom cannot be had without first declaring and defining what one is breaking free from.

In one sense, it is Valledor who receives his long overdue attention and emerges to the foreground in this exhibition—not that Villa’s work appears secondary. Art historically, it is actually the opposite—Villa is, especially in recent years, heralded as a major figure in Asian American art, while many are still learning about Valledor. This is partially due to the fact that Villa’s activism, curating, and teaching came together both with and through his art, while Valledor sought to achieve everything within the space of painting. Even the historic downtown Park Place Group, which is now known for artists such as Mark di Suvero that Valledor was part of as one of the founding members, was itself an anomaly of that time and free experimentation among their artists made them hard to categorize. And then for Valledor, something like teaching was more a source of income, separate from his practice. It is also the crude reality that Villa outlived Valledor and therefore had more time to shape his work and legacy.

Regardless, one element that this exhibition makes undeniable is that art historical categories have been insufficient for prolonging the memory of artists like Villa and Valledor. Villa, who has enjoyed more notoriety, still deserves more looking and research on his formal innovations and redefining of abstraction. Conversely for Valledor, while it might superficially seem that his work is “western” and apolitical, works like We Shall Overcome (1983), which anchors the entire exhibition, stand to rebuke such reductive assessments. While many recent curatorial efforts have been offering correctives in art history—to the chagrin of some art critics—“Carlos Villa and Leo Valledor: Remains of Surface” show that it is not so much correction as much as restructuring that is necessary.

Going back to their early life, when Carlos and Leo were boys figuring out how to be men, they looked to Black culture (which included both of their life long love for jazz) and to their uncles, even as those uncles frequented taxi-dance clubs, paying women a dime for a dance, as more Filipino men were brought to the United States than women as low wage laborers. In my conversation with Mary Valledor, she recalled, “Carlos, he would find a flashy, cool leather jacket. Leo would wear painter’s pants, but he would keep them clean and pressed. Style was very important to them.” This “performance of presence” as fellow artist and curator Patrick Flores calls it, may have resulted from not being seen, but they lived and made work with a bold openness, preparing to be seen, knowing they will be seen.