“Between Waves” Dives Deep into Asia-Pacific History

Water is both a metaphor and a character in “Between Waves,” the eighth installment of The Brooklyn Rail’s “Singing in Unison” series. The group exhibition, featuring contributions by 17 artists and curated by Alice, Nien-pu Ko, immerses visitors in the complex histories of the Asia-Pacific region. Composed primarily of large-scale video projections packed densely on the ground floor of a repurposed factory building in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, “Between Waves” lives up to its title, enveloping viewers in intersecting waves of light and sound.

Owing perhaps to the formidable scale of the projections, the waves on screen seem to extend beyond the boundaries of their respective works, making the entire gallery feel submerged and enclosed. Meanwhile, as viewers traverse the exhibition space, they occasionally cast their shadows on the works. This happens with Lieko Shiga’s video installation When the Wind Blows (2022-2023), in which performers dressed in black tread somnambulantly along a blustery sea wall. As viewers superimpose their silhouettes on the scene, a sense of imbrication and immersion emerges. Several artists in the show harness this sensation and use it as a gateway into their historical deep dives.

In Jane Jin Kaisen’s single-channel video Offering – Coil Embrace (2023), for instance, the artist collaborated with female divers from the self-governing province of Jeju Island, South Korea, to create a slow-motion underwater choreographed dance with sochang cloth. Featuring the white fabric unfurling in the midnight blue fluid of the ocean and close-up shots of women’s faces contorted in expressions of pain, the film’s mise-en-scène conjures a metaphorical space teeming with natal associations and symbols of matriarchal power. While an understanding of these images’ emotional depth doesn’t require prior knowledge, the specificity of Kaisen’s collaborators and their profession—diving to harvest mollusks and seaweed in the Korea Strait—embeds layers of historical, spiritual, and ecological context within its mesmerizing visuals.

Works by Vandy Rattana can also be read as an immersive history lesson. In Funeral (2018), a slow, atmospheric narrative unfolds, tracking a funeral procession in a Cambodian forest. The procession includes male pallbearers and a young girl, who take turns breaking away to stare at the landscape. At one point, one of the men turns and contemplates his reflection in a rippling pond. What visually resembles a moment of self-reflection is complicated by the trauma imbued in this site: Rattana’s practice excavates painful episodes from Cambodian history, particularly the Khmer Rouge and the American carpet bombings of 1969-70. In Funeral, a seemingly innocuous image of water begs to be read as a text—as, to quote Roland Barthes, “a tissue of citations.” Through layers of reference, Rattana, like Kaisen and others in “Between Waves,” gracefully sidesteps the trap of anthropocentrism, calling on viewers to pause and listen to the natural world.

It’s fitting that for an exhibition centered on a region of islands, archipelagos, and sea-oriented countries that share memories of colonial and Cold War conflicts, artists drew on water as a metaphor for solidarity. At the same time, water appears not only as a signifier but also as a character, possessing the spirit and dignity of a living being. In Irwan Ahmett and Tita Salina’s single-channel video The Call of Fragility (2022), a flood engulfs a fishing village in Java. Aerial footage shows flat rooftops as a patchwork of colors and textures, mounds of debris as motley patterns, and the encroaching water as a smooth and indifferent force in comparison. From above, humans wading through the flooded streets appear infinitesimal, while the natural world takes center stage as the awe-inspiring protagonist.

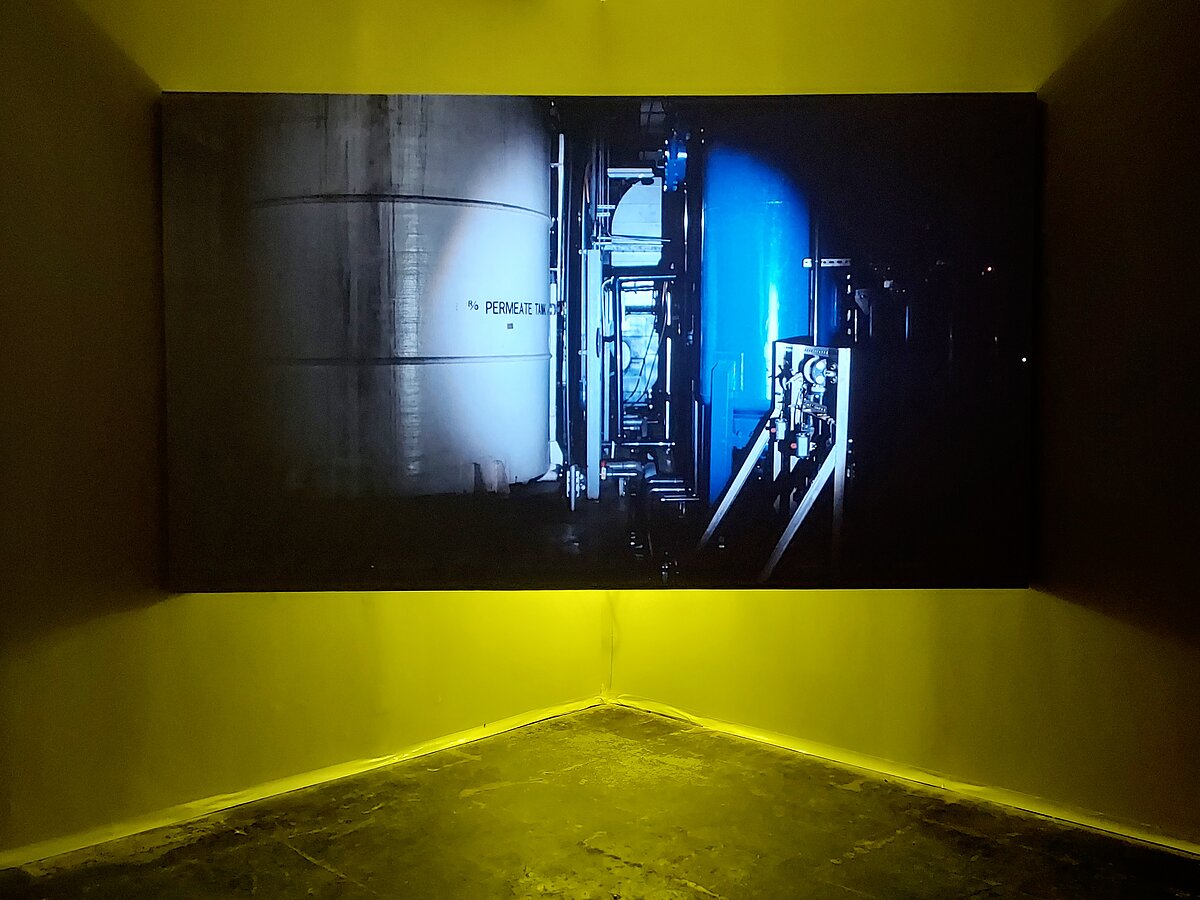

Similarly, in Su Yu Hsin’s Particular Waters (2023), water takes on the role of a stoic hero, against whom the absurdities of human enterprise are laid bare. In this single-channel video, which encapsulates the exhibition’s ecological and techno-critical concerns, Su calls attention to the unsustainable quantities of water—tens of thousands of tons per day—required to produce advanced semiconductors at a Taiwanese foundry. The video follows a foundry employee as she drives a tanker to two local reservoirs in the chip manufacturing hub of Hsinchu, Taiwan, where the water supply has dwindled due to drought (in one shot, a sign that reads “Warning! Deep Water No Entering” ironically looms over a dry riverbed). Despite this, the driver nonchalantly siphons water—along with algae and other living organisms—into the belly of her truck.

In the face of anthropogenic climate change, it’s difficult to avoid reading depictions of water in art as either portentous or elegiac—and easy to forget that water is also a symbol of change, circulation, and adaptability. At the end of Hsin’s Particular Waters, we cut to a nighttime scene beside a flowing river and spend a brief minute in a realm of ambiguity: we see the foundry employee crouching at the water’s edge with a flashlight. Instead of extracting, she is exploring.

Just as political power is forged in what Alexis de Tocqueville termed the “art of joining”—as The Brooklyn Rail has set out to argue through this exhibition series—there is strength to be accessed in the memories of disparate waters, all of which have borne witness to the world’s atrocities, upheavals, and rebirths.