An Art Book with Teeth: Tammy Nguyen’s “O”

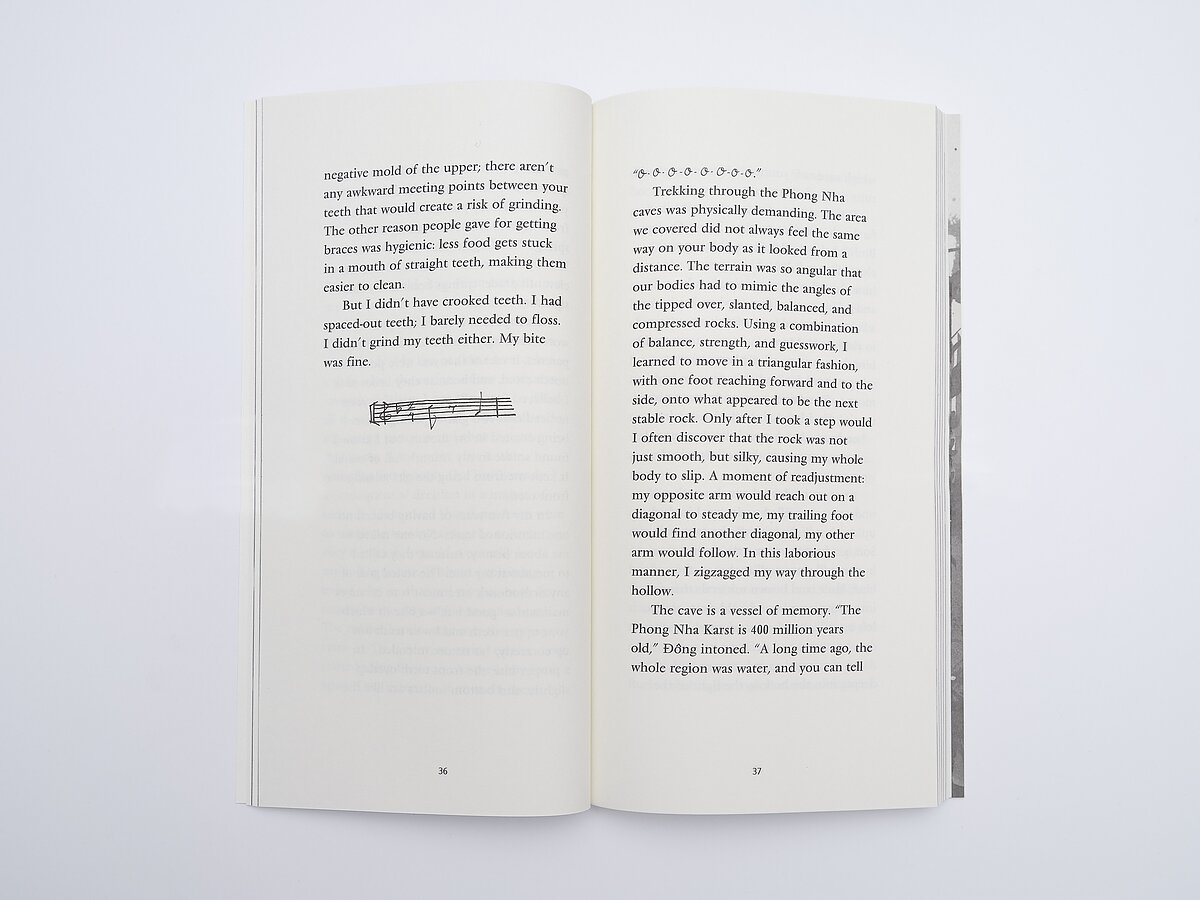

Multimedia artist Tammy Nguyen’s new book O, published this year by Ugly Duckling Presse, weaves together stories about the artist, her family, and a series of anthropomorphic caves in Vietnam. The narrative begins with a personal account. We meet the artist as a young girl in a dentist’s chair, confused beneath the capitalist medical gaze, her throat producing the involuntary gurgle—“O-O-O-O-O-O-O-O”—that becomes the book’s sonic refrain. The discovery of her congenitally missing lateral incisors, a perceived imperfection, sets off a chain of pricey dental procedures that hound her on multiple continents.

What follows is a meditation on the wind that carved the ridges of the cave-riddled Phong Nha mountains—“the Earth’s teeth,” according to Chinese mythology—approximately four hundred million years ago. As evidenced by this seismic shift in time and space, O holds its polarities—deep and recent history, the sublime and the mundane, the built environment and the wilderness—on facing pages, in intimate proximity. Nguyen’s most powerful assertion here is that a surgically constructed “American smile” can carry as much symbolic heft as the limestone walls of ancient caves.

Measuring 4.75 by 9 inches, O is a slim, stately book. The text inside is printed in long columns, as if to mirror the formal qualities of the book’s spine. In interviews, Nguyen has emphasized the importance of the spine as a physical and conceptual structuring device, stating, “The spine is a built structure that gives us a physical parameter and conceptual foundation for the experience of an artist book.” Holding the perfect bound book, your hands feel close to its built center.

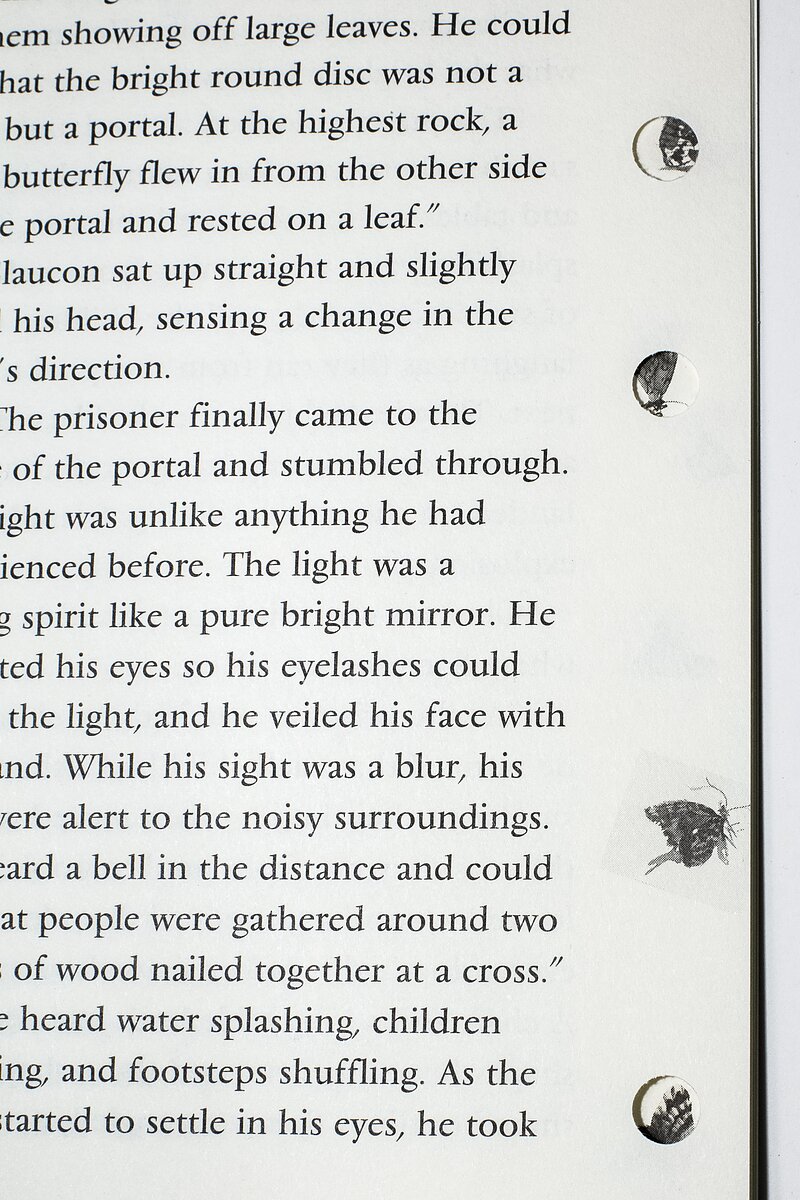

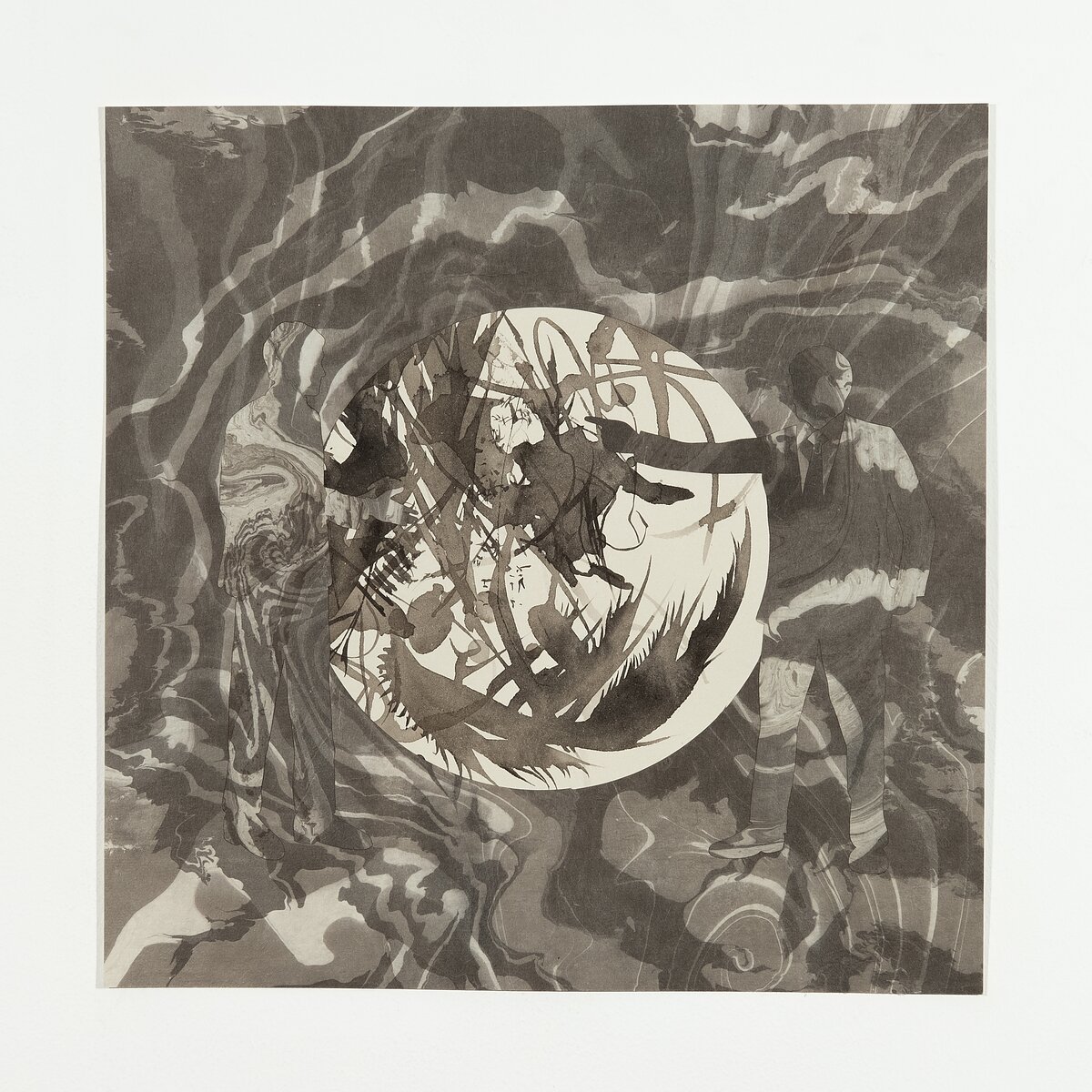

Image spreads that appear throughout the book also interact with its long spine. These images are prints of works on paper depicting moon-like discs inked in various abstract phases, partially obscured by leafy vegetation. Because the book does not lie flat, the spine creases and inhales these circular forms. Toward the end of the book, however, a vista unfurls from the once unyielding spine, as a pair of exquisite laser-cut foldout pages send silhouettes dancing across inked foliage in varying shades of gray.

If the crowds at the Printed Matter Art Book Fair, where I first encountered O in the flesh, and the number of exhibitions and spaces dedicated to book arts in New York and beyond are any indication, codices that dwell in between the textual and the visual have proven to be fertile ground for conversation and collaboration. In 1995, visual theorist Johanna Drucker declared artists’ books to be “the 20th-century artform par excellence,” and their singularity, I believe, carries on into the 21st century.

Nguyen inhabits and expands the codex’s material boundaries in the spirit of polyphony and play. O has been compared to such pillars of diaspora literature as Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée and Sophia Al-Maria’s The Girl Who Fell to Earth: A Memoir. To that list I would add artists’ books like Romano Hänni’s It is Bitter to Leave Your Home and Jihae Kwon’s Stratum, which, like O, utilize the meeting of text and image to explore lacunae as originary and irrefutably intimate as missing teeth.

–Jenny Wu is a writer and independent curator.

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul.

Photography by Daniel Kukla.