Photo Essay: Remembering Iran’s Past, Imagining Its Future at Disco Tehran

By Sunny Shokrae

November 1, 2022

Essays

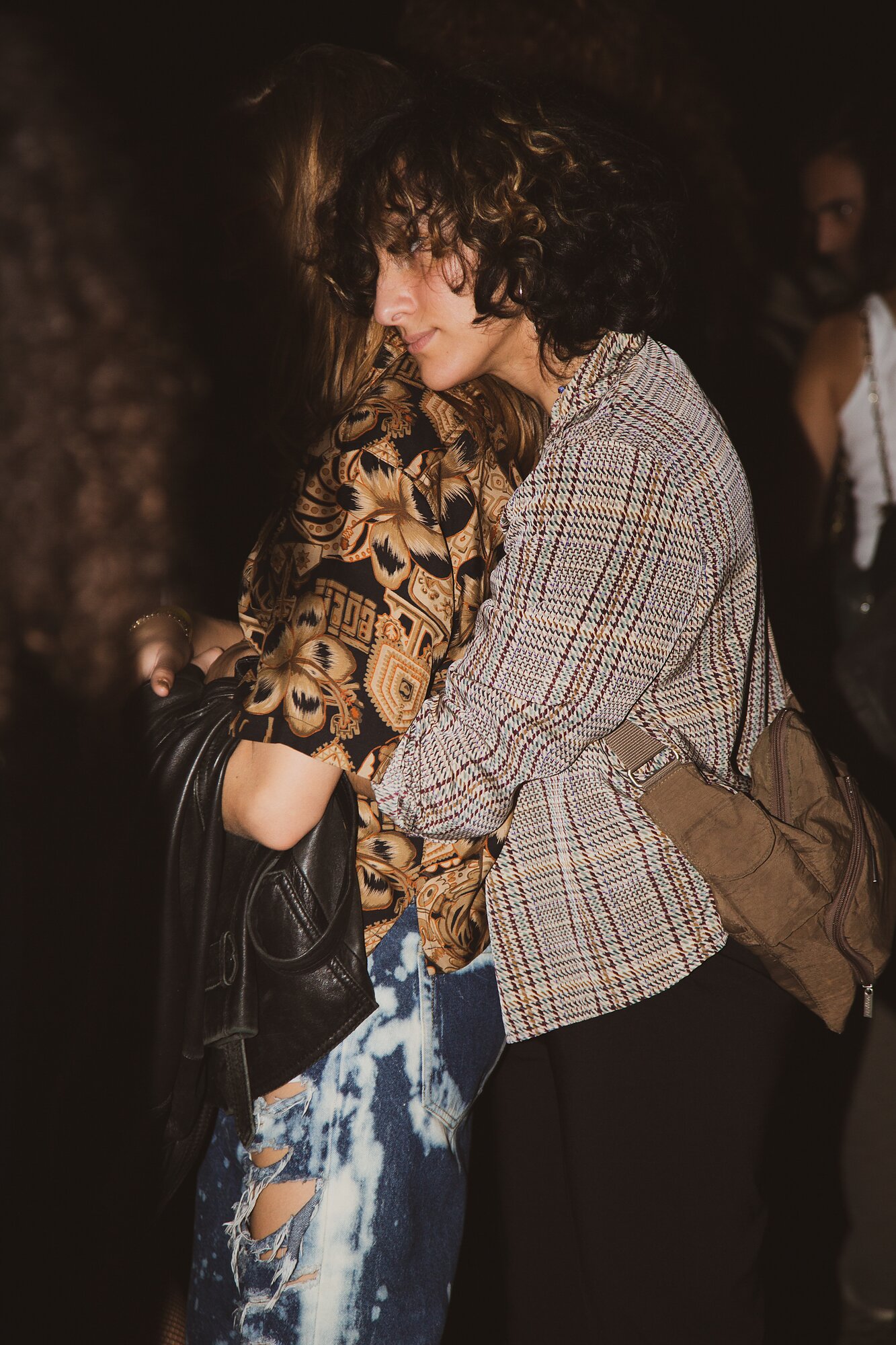

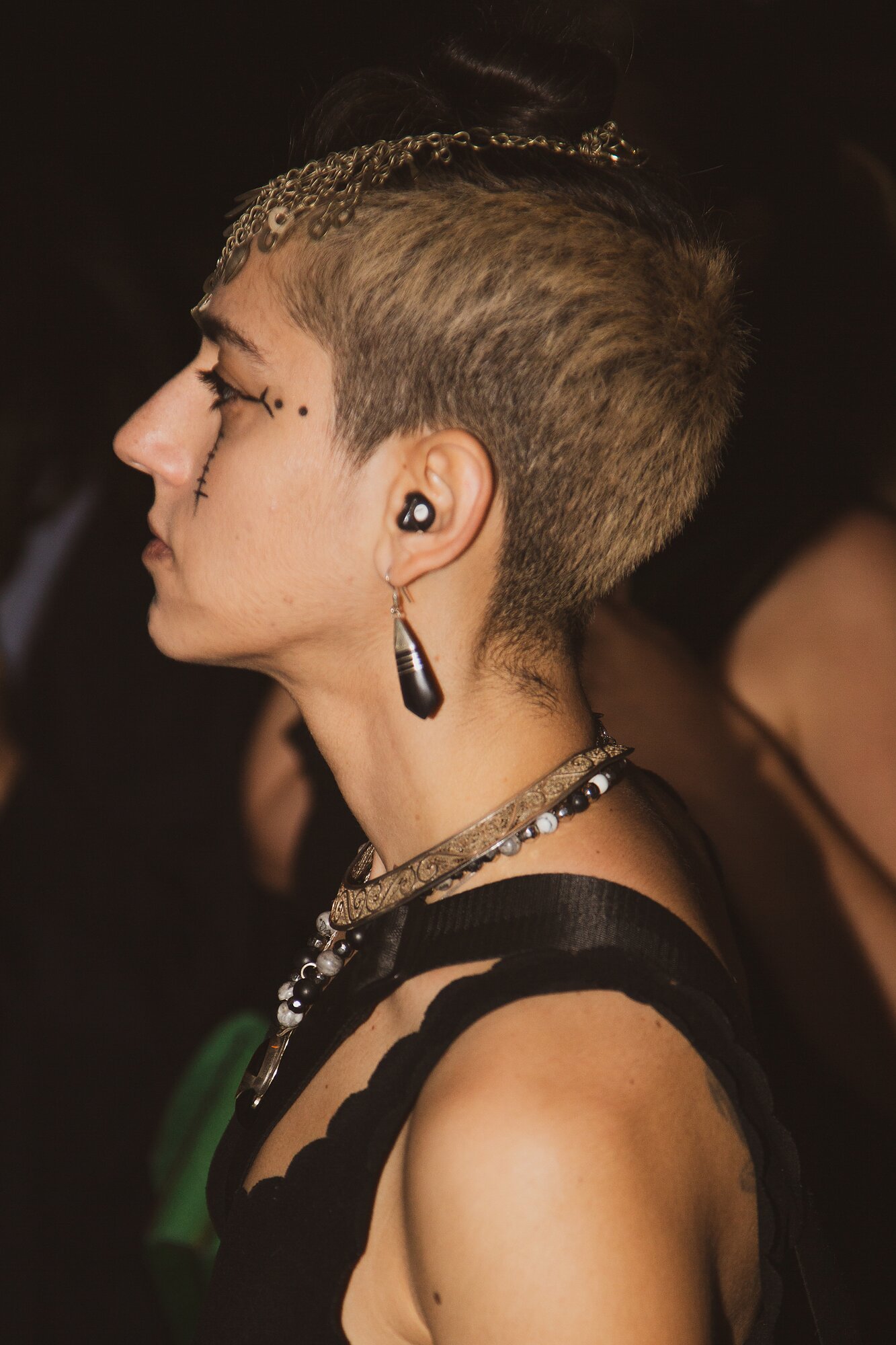

I remember when I first heard about Disco Tehran back in 2017. I was thrilled that there was a space to connect with other people like me, to dance to music I only listen to in my own home, and to discover more of it. Created by Arya Ghavamian and Mani Nilchiani, the event and performance project reimagines the Iran of the 1970s, before the revolution of 1979 was hijacked by an oppressive Islamic Regime. Since its first intimate, NY apartment-held dinner and dance gatherings, Disco Tehran has evolved into a much larger affair, fusing together people from all walks of life. It’s an event lathered in joy, celebration, and the healing qualities embedded in music and allowing your body’s intuitive movement to take reign. What draws me in is its celebration of diversity and the Iran that I was never able to know personally—the one that allowed public dancing, women singing, and freedoms that have since been stripped away.

The event and performance project reimagines the Iran of the 1970s, before the revolution of 1979 was hijacked by an oppressive Islamic Regime.

In the midst of tidal waves of protests and deadly nationwide crackdowns, Disco Tehran held a final New York event in October in solidarity with the people of Iran. This moment was ignited by the inhumane murder of a 22 year-old Kurdish woman, Jina Mahsa Amini, at the hands of Iran’s morality police, a force that revels in the fear and paranoia they cause by enforcing “morality” laws with intentionally confusing inconsistency. It has been over 40 days since her death and since then, according to reports, over 250 protesters have been killed, children included, and 12,500 arrested. That number is likely much higher in reality. The internet has been shut down throughout the country; proceeds from Disco Tehran’s ticket sales went towards their ongoing VPN project providing ad-hoc internet access to people in Iran. I’m thankful for Iranian journalists, many of whom are now suffering in solitary confinement, for getting these stories out despite the harrowing and violent threats made to them and their loved ones.

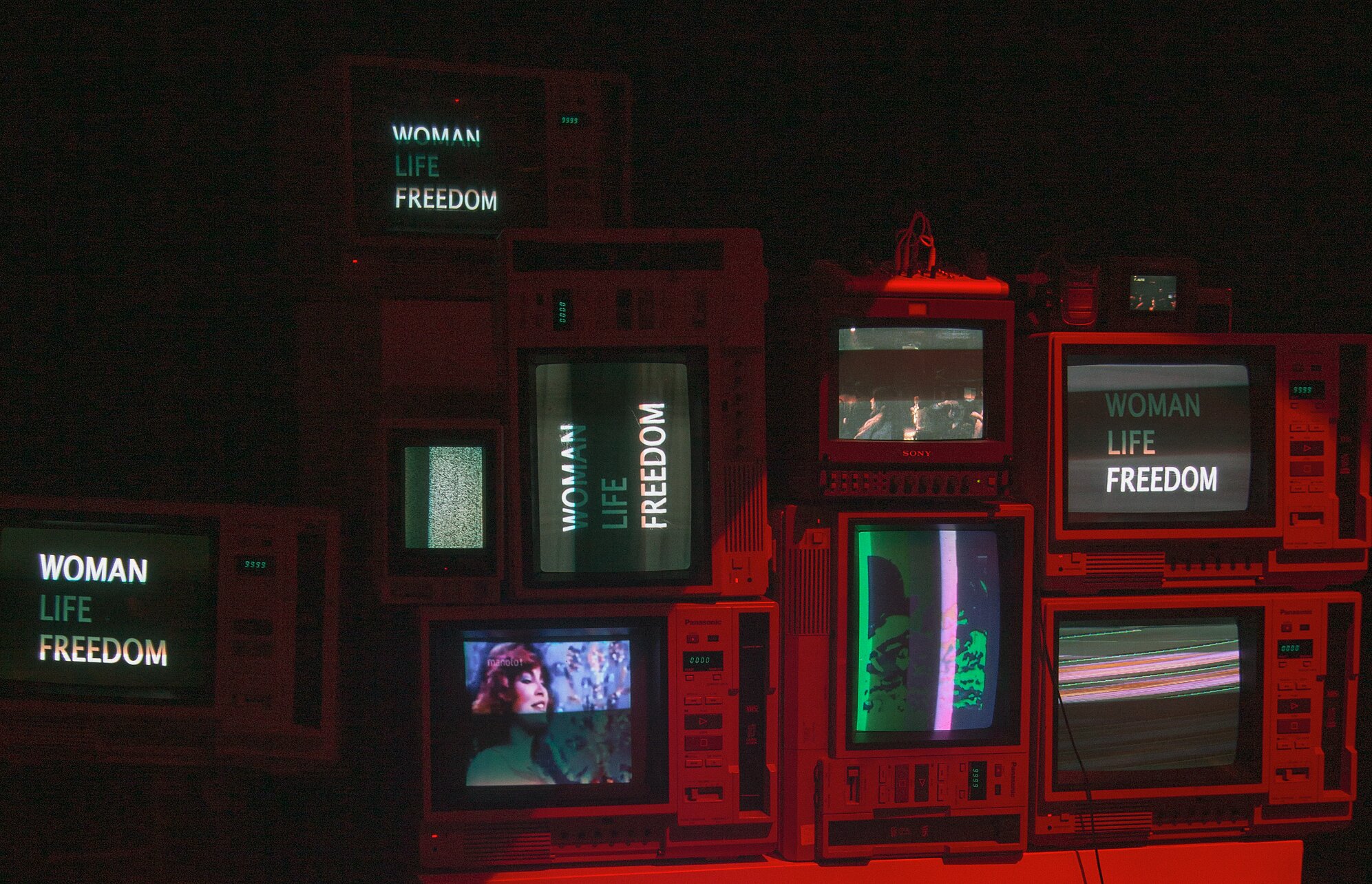

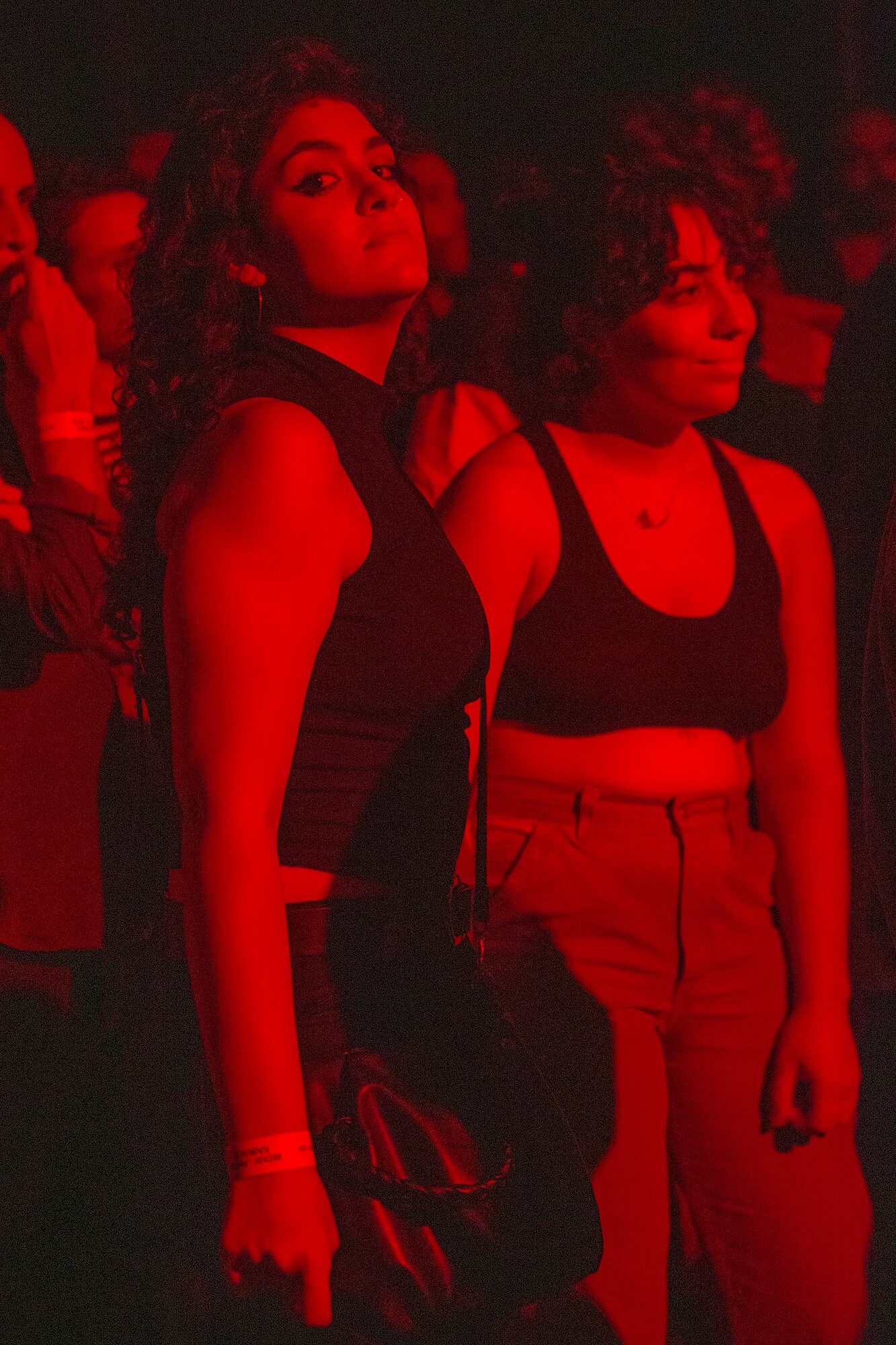

In the period leading up to Disco Tehran, it was hard to tell whether this celebration was still going to happen. I personally felt like I had been at an unending funeral for weeks and any glimmer of joy was far out of reach. Revolutions are bloody, long, and painful. But the event stayed the course, and when I arrived at its Bushwick warehouse venue, I was met with a place to pen a message to Iran. “I’m so sorry,” I wrote. That held me. From there, a TV installation put into view what so urgently needs attention: Woman. Life. Freedom. These words were accompanied by moving images and names of the young lives lost before and during the protests. That fueled me. I looked around and saw people seeking comfort, needing a break and a release. It was then that I noted that this event, in itself, was an act of radical resistance—to dance, to love openly, to lean into freedoms we may otherwise take for granted.

Iranians keep sharing the same stories over and over, reliving personal traumas because this struggle is unprecedented and we need everyone to pay attention. The world needs to understand that the Islamic Republic is not Iran. The Iranian people are Iran and the Regime’s greatest victims are its own people. These people are demanding control of their country and their liberty and there’s no going back. I’ve noticed a reluctance in public solidarity on the part of my non-Iranian friends. As an ambiguous-looking Middle Easterner, I recognize that people like me are often confined to narrow dimensions of perception, specifically those which come out of events like 9/11 and a western lens that Others us. But if I’ve learned anything through storytelling it’s that being detailed in how you unpack your own emotional experience is the best way to connect and relate to people that don’t look like you or come from where you come from. Building community and relishing in the support of that community is a way to fight oppression and usher a life beyond just survival.

The world needs to understand that the Islamic Republic is not Iran. The Iranian people are Iran and the Regime’s greatest victims are its own people.

My longing for Iran is unquenchable. For many who move to a foreign place at a young age with their families, I imagine there’s a romanticization of home and a level of inadequacy that stirs within as we try to gain footing in a new culture. I have been playing an unsustainable game of mental gymnastics for the last month. I have been trying to gain the slightest bit of control in any way possible to support the ongoing protests and push for change in the country I was born in—but not raised in—while not allowing everything else around me to crumble.

There isn’t a single Iranian, inside or out, that I know who hasn’t been hurt by the current Regime directly or otherwise.

For every feeling of guilt about my privileged life lived away from Iran’s hardline theocracy; for the feelings of displacement growing up; for the hidden pain I see behind my parents’ eyes; for all this confusion, grief, and loss…there isn’t a single Iranian, inside or out, that I know who hasn’t been hurt by the current Regime directly or otherwise. And yet, I know the crisis my heart and mind experiences daily is but a speck compared to the crisis the people in Iran are experiencing as they fight this war against decades of discrimination, state sponsered violence, control, erasure, and patriarchy.

It’s difficult to process everything that’s happening at this moment, especially with decades of buried emotions actively boiling up to the surface. It’s happening so quickly, without a moment to reflect; a constant waterfall of information every morning coupled with information suppression and reports of so many young lives taken. Processing may not be attainable right now, but participation is unavoidable. We do what we can within the walls of our own community, with the painful understanding that, as active participants, we may no longer visit this country we love so deeply (anyone that even speaks against the current system becomes a target, no matter where they live).

Processing may not be attainable right now, but participation is unavoidable.

It has been essential, in this critical moment, to create art, make connections, and establish new social channels throughout the diaspora. It is within these spaces that we are able to re-fuel in order to continue to take action in support of the people we love and the home that we left. As the people inside fight for a new chapter, a brighter future, and a more equitable road ahead, we create and act with the hope that this time, it will be different. This time we will have liberation, both inside Iran and abroad.

–Sunny Shokrae is a photographer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, I-D, Oyster, Bon Appetit, and Fader Magazine. Her clients include Tiffany & Co., Barneys New York, Converse, and Levis. Her work, whether it be portraiture, fashion, commercial, community-focused, or personal, centers her subject(s) and exudes them, and her vision, in a way that feels intertwined, inviting, and intimate. She touches on moments of stillness and flux, demonstrating an ease and fluidity that is both current and enduring. She currently lives in Brooklyn with her partner and son.