Reflections of an American Soldier

[CW: Suicide, graphic descriptions of violence.]

I remember when the suicide of Private Danny Chen was reported back in 2011. He was only 19 years old—just two months into his first combat tour in Afghanistan and half a year removed from boot camp. A baby soldier. A baby. Though I never met him, his life and tragic death left an ache I still feel today.

Written in the years following, An American Soldier is an opera scored by Huang Ruo with a libretto by David Henry Hwang that accounts for the distinctly American conditions that led to Chen’s death. This past spring, the production returned to the stage at the Perelman Performing Arts Center—just a few blocks from Chinatown, where Chen grew up.

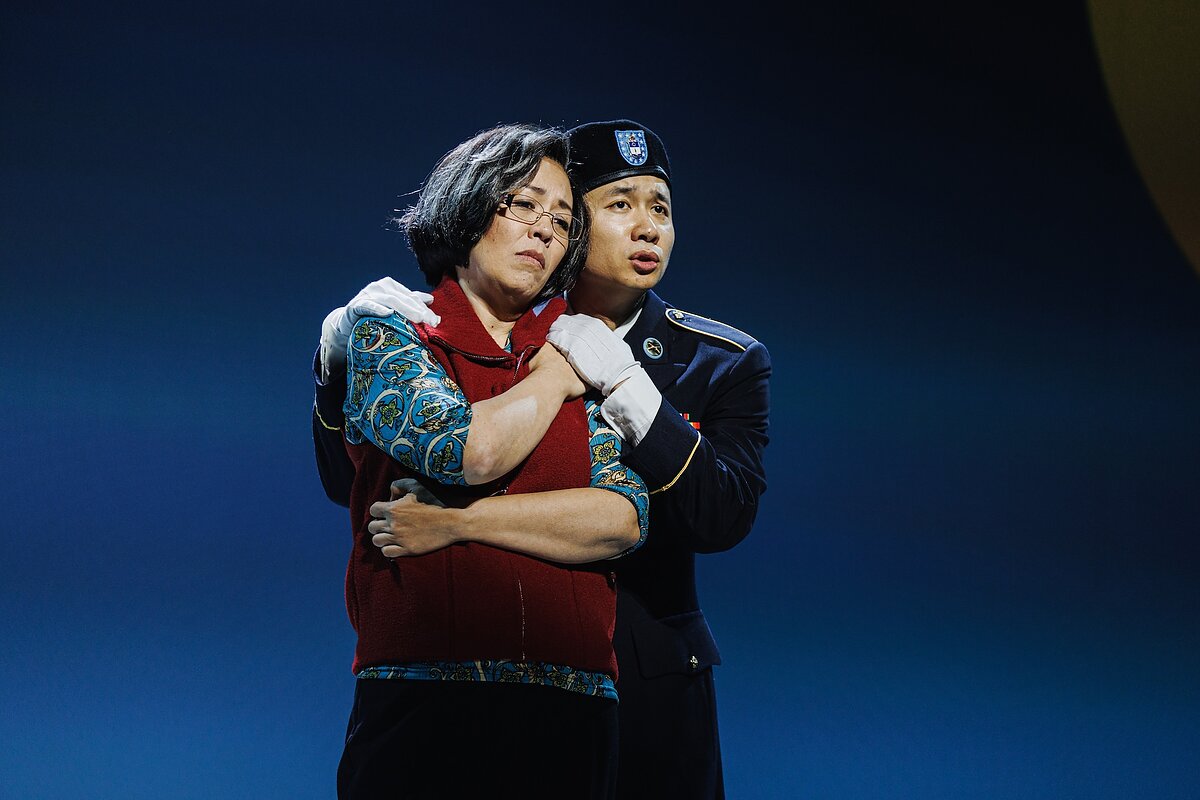

The opera begins with the court martial of eight members of Chen’s unit who were charged with complicity in his suicide. As the case is revealed to us, we learn that Chen, played by Brian Vu, was subjected to racialized hazing and punishment to the point of being tortured by his peers and superiors. The production expertly intertwines scenes from the trial with flashbacks of Chen with his loving family and friends. Nina Yoshida Nelsen plays the role of Chen’s mother to devastating effect. It was a haunting and powerful experience that stayed with me long after I left the theater.

Chen and I have a lot in common, both being Chinese Americans from New York City’s Chinatown who enlisted in the US army and were deployed to South West Asia after 9/11. Like Chen, as a young man in the early ‘00s, I struggled in my search for belonging and looked to the Army as a place to prove my worth.

I was eight years old when my family immigrated from Hong Kong to New York City in 1983. We didn’t speak English. My dad was a baker. My mom was a bank teller. They found work and a home in Chinatown, where they stayed for over 30 years owning several bakeries.

I read that Chen’s mother came to New York by herself. His father would follow a few years later. Chen’s father worked as a chef. His mother was a seamstress. Chen was born in Chinatown in 1992.

Chinatown gave immigrant families like ours a solid ground to build from. Those 50 blocks of Lower Manhattan allowed us to be self-sufficient. My parents worked long hours to support the family, leaving my older sister and I to raise ourselves. I read comics, played sports, and was the co-captain of my high school track team.

As I grew older, I began to understand that my appearance preceded me. No matter how I felt in my heart or what I did, I’d always be a hyphenated American in my own country. I couldn’t parse those feelings as a kid, but I have come to understand how I felt hurt by it.

Racism in the ‘80s and ‘90s was normal. Growing up, I heard every slur and taunt. Even into my late 20s, I would be told to go back to my country over minor disagreements. Yet, living in New York City, I wasn’t too bothered by bigoted words. There were so many Asians here and I felt protected. I wasn’t alone.

It wasn’t until I went to college in Buffalo, New York and was away from familiar faces that I began to feel truly alienated. I made the track team my freshman year when the school just joined Division 1A. I was excited to be part of something and to be an Asian American D1 athlete—there weren’t too many of us at the time.

During our first team meeting, I accidentally walked into the football team’s locker room. It was packed and I was startled. I heard someone loudly say, “Who the fuck is this Chinese guy?” like I was delivering fried rice. My face went numb. I blanked and left immediately. I never told my team about it and I ghosted soon after. That was the entirety of my Division 1A track career.

Raised in a one bedroom apartment on Elizabeth Street and later a housing project on Avenue D, much of Chen’s young life revolved around Lower Manhattan. He did well in school and received a full scholarship to Baruch College. He was tall and played handball with his cousins and collected Yu-Gi-Oh cards.

Chen dreamed of becoming a police officer and, as he got older, a soldier. In a 2012 New York Magazine article, Chen’s best friend, Raymond Dong remembered how Chen strove to break away from the typical immigrant trajectory. “I want to live for myself,” Dong recalled Chen telling him, “not for someone else.”

In 2010, without his parent’s knowledge, Chen enlisted as an active duty infantryman in the Army instead of going to college. Dong recollected telling Chen, “You could do a lot better than join the Army. You’re so smart.”

In An American Soldier, Dong is replaced by a female love interest by the name of Josephine (played by Hannah Cho). When she learns of Chen’s decision to enroll in the Army, she asks him,“What kind of Chinese are you?”

Many felt the same about me. I, also against my parent’s wishes, enlisted in the Army Reserves when I was 24. Enlisting was a way for me to escape my parent’s expectations and demands and an opportunity to live my own life. For my parents, however, my decision was a betrayal of all the sacrifices they had made for the family.

Chen and I landed at Fort Benning, Georgia for basic training about ten years apart. Boot camp was as difficult as I had envisioned it to be. It pushed me to the edge, both mentally and physically. My platoon of 60 slept in an open bay consisting of 30 bunk beds. We did everything together, night and day.

While I don’t recall any overt racism during basic training, there was an abundance of inappropriate comments. Drill Sergeants would call me Jackie Chan or Bruce Lee. Some members of my platoon confessed they had never met a Chinese person before. I thought to myself, not one? How is that possible?

During his basic training, Chen wrote in his journal that other soldiers teased him constantly for being Chinese. “Everyone here jokingly makes fun of me for being Asian,” sings Chen in An American Soldier. “People crack jokes about Chinese people all the time.”

Watching the opera, I laughed nervously during scenes where Chen’s character was being made fun of—I’ve been there. In the Army, we were told it was something we had to overcome as part of our journey. The goal of boot camp, as it was drilled into us everyday, was to turn us into killers. This was all part of the training doctrine—dehumanize privates and reset their minds until they can follow orders and perform inhumane tasks when needed. While in boot camp, my singular focus was to simply get through it. It never occurred to me to try and change it.

I graduated basic training in 2000, Chen in 2011. As a reservist, I came back home to New York. My parents sold the bakery I previously managed and I took a clerical job in Building 4 of the World Trade Center in late 2000. In early 2001, I was transferred to a recently opened second office in midtown.

On September 11, the first plane had already hit the first tower when I got to work. Standing on the street, I watched the second tower fall. I never found out if everyone I knew from the old office made it out okay.

My unit landed in Kuwait on Thanksgiving of 2002. By the time Chen landed in Afghanistan, it had already been ten years into the inexplicable 20 year “War on Terror” the US was waging and ten years since 9/11. Osama bin Laden had already been killed and the mission was very different from when I was there. I don’t think politicians even knew what the mission was anymore. Moral clarity is always ambiguous in war. Coupled with bad intentions, we became the very terror we were supposedly eliminating.

Unlike me, after basic training, Chen went to his permanent duty station in Alaska before getting deployed to Afghanistan. In 2011, Kandahar Province was considered one of the most dangerous places in the world. Less than two months later, Chen was found dead, killed by a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

In An American Soldier, during scenes of court testimonies, Chen is characterized as having been ostracized and frequently punished by his superiors as a result of underperforming. Flashbacks show Chen being accused of leaving a water heater on after showering and falling asleep during guard duty—serious offenses in a dangerous outpost.

Other witnesses, however, also describe how Chen was targeted specifically because of his race. According to what Army officials relayed to Chen’s family in the months after his death, a group of Chen’s superiors tormented him on an almost daily basis over the course of about six weeks. The only Chinese American soldier in his station, Chen was ordered to instruct fellow platoon members in Chinese and do push-ups while holding water in his mouth. They repeatedly called him slurs like “gook,” “chink,” and “dragon lady.”

The opera’s apex begins on the day of the water heater incident. A sergeant pulls Chen out of bed in the middle of the night and drags him outside over gravel as punishment. A few days later, Chen reports to his tower duty without his helmet. He is sent back to retrieve it and ordered to crawl the 300 feet back to his post over the hard gravel. His superiors begin hurling rocks at him. Other platoon members join. Chen is then grabbed by his armor and dragged again up the steps to his station.

On stage, we see Chen’s silhouette in the watchtower from a distance as he lowers its blinds. The sound of a gunshot rings suddenly through the theater; Chen has taken his own life. In an autopsy report, a medical examiner noted that the words “Tell my parents I’m sorry,“ and "Veggie—pull the plug” were scrawled on his arms.

In combat, your unit is everything. I was lucky. My platoon in Iraq was tight. Most of us wouldn’t hesitate to risk our life for each other. We joked a lot and complained a lot. It’s the type of bond I will never experience in the civilian world.

Chen walked into the opposite. Instead of mentoring and guiding him as they are expected to, Army leaders tortured Chen like an enemy. Maybe it was racism, poor morale, or a unit full of sadistic humans; likely a combination of all three. They broke his young heart, body, and mind until he couldn’t take it anymore.

With persistent pressure from community advocates and Chen’s parents, the Army eventually arrested eight members of his unit. The charges ranged from dereliction of duty, making false statements, involuntary manslaughter, negligent homicide, and assault. Lt Daniel J. Schwartz, the highest ranking officer among the eight, took a plea deal and was dismissed from the Army. The other seven were given demotions and short prison sentences ranging from three to ten months—slaps on their wrists. All were allowed to stay in the Army. No dishonorable discharges came as a result of the trial.

In 2014, a portion of Elizabeth Street at the heart of Chinatown was renamed Private Danny Chen Way. At a memorial service commemorating Chen’s life this past fall, civil rights attorney Elizabeth Ouyang reflected on Chen’s legacy: “Asian Americans who want to protect our country will have second thoughts if our country cannot protect them.”

When I returned from Iraq, I came back with medals and combat badges and the feeling that I no longer needed to worry about others’ opinion of my Americanness. I felt I’d earned my right to be an American when most merely lucked into it. I thought life was good in my part of the world, even if the headlines suggested Iraq was deteriorating into chaos.

I did drink a lot—all day at times. I would cry in unexpected moments. I kept parts of myself separated and tried not to think too deeply about it. Like many veterans, I was stuck in war mode long after I came home.

I left the military completely in 2011 and floated through life for the next decade. I had a baby boy and qualified for the GI Bill. I used it to study art, which forced me to reflect honestly on who I was. I learned about a different kind of patriotism, inspired by writers, artists, and thinkers like James Baldwin, Nina Simone, and Angela Davis.

It was hard to keep pretending the wars I had fought in were right. The invasion of Iraq was illegal and no matter what the Taliban did, it didn’t justify the irreparable damage we inflicted in Afghanistan. Hundreds of thousands innocent lives were taken. Millions more were injured and displaced. We created more enemies in the process. All of this was the result of US involvement.

The reality of my mental health sank in. I had sought mental help before, but never could stay with it. I couldn’t bear the possibility of leaving my son, who was in elementary school at the time, with the kind of baggage and burden that could come as a result of not dealing with myself. I went to the VA for help and committed to it. It took two years of therapy and medication but it changed my life. With their help, I reconciled all the separate compartments into one—no more fighting myself subconsciously.

Life is mostly staying alive and evolving. I’m grateful for who I am today but none of it alleviates my accountability as a soldier in Iraq. I’m not the victim in my story. No one forced me to join the Army or go to Iraq. I did it because I was young and selfish. Like Chen, I wanted to fit in and belong in America. I was happy to overlook all the killings and injustices if it meant I could be seen as more of an American. Like Chen, I was ultimately betrayed by those pursuits. I was lucky enough to survive.

Maybe the most patriotic thing we can do is be less American. When I think about my son and how he navigates his own coming of age, I hope he doesn’t measure himself against the status quo. America isn’t well and needs more from us. It needs therapy and a hard look in the mirror. Instead of finding a spot in a violent and oppressive hierarchy, we should help evolve this country to be more just for everyone.

—William Chan is a mutual aid organizer, activist, and lecturer. His works on Iraq are taught and held at institutions such as the Tim Hetherington Library at the Bronx Documentary Center, Tate Modern, Yale University, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, and Harvard University, among others.