“Public Obscenities” Subverts What’s Expected of a Queer Indian Play

As audiences settle into their seats at the Theatre for a New Audience’s cozy Polonsky Shakespeare Center to see Public Obscenities (running through February 25), they might be expecting a certain sort of play—a queer and Indian play. These words carry a certain connotation, breeding a certain expectation from American audiences. It’s near the beginning of Shayok Misha Cowdhury’s play, however, that this expectation is dashed.

This adjustment of viewing the work through a different lens is reflected on stage as Raheem (played by a brilliant Jakeem Dante Powell) fiddles with his boyfriend’s grandfather’s camera and says, “I’m just getting used to looking through this viewfinder.” Like Raheem, the audience adjusts, and then, in the capable hands of the show, are taken on a journey.

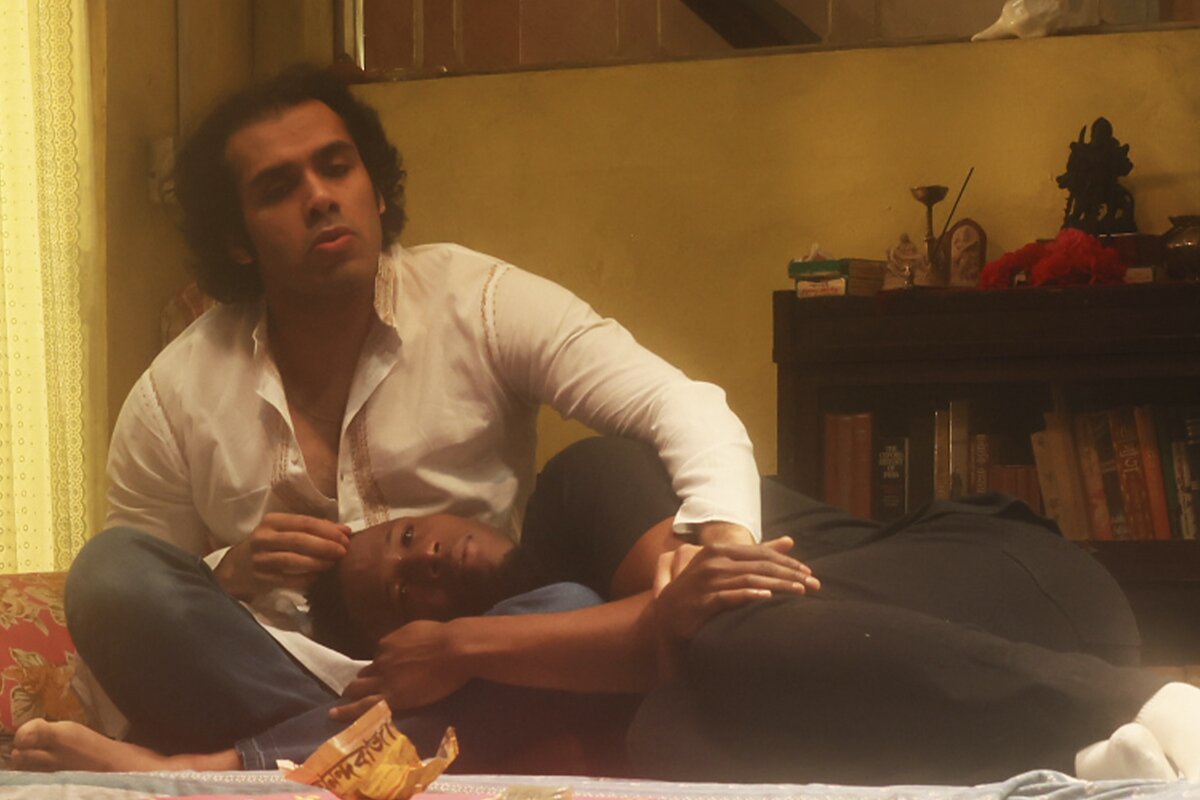

Set in current-day Kolkata, Public Obscenities follows Choton (played by Abrar Haque) as he brings his boyfriend, Raheem, to his aunt and uncle’s home, both to meet his family and film a documentary. The play revolves around these same characters; Chotu’s boisterous and effusive aunt and uncle, Pishimoni and Pishe (played by Gargi Mukherjee and Debashis Roy Chowdhury), and their housekeeper, Jitesh (played by Golam Sarwar Harun).

Through Choton’s project, audiences are treated to a brief glimpse of India’s rich hijra culture, thanks to the effervescent Shou (played by Tashnuva Anan) and Sebanti (Nafis). But what starts as Chotun and Raheem’s attempt to interrogate and document queer culture in India expands far beyond anything they might have imagined. Through the act of filmmaking, the play asks the viewer to interrogate their relationships between what is hidden and what is shown, the lens with which we view ourselves and our families, and how the act of translation can bring us together, even as they seemingly keep us apart.

Chowdhury immerses audiences into the intricacies, secrets, revelations, and coming together of a family in modern-day Kolkata. Over the course of the play’s grand three hour run time, audiences get an intimate look at each character. Despite its long runtime, the script remains tight and manages to feel nearly breathless as it covers the ground of only a few pivotal days during Chotun and Raheem’s visit. Indeed, it is the long runtime itself that aids the play in feeling so gripping and enthralling.

The show becomes intensely immersive by mere virtue of the fact that we are allowed to watch time move on carefully, instead of being shuttled abruptly from scene to scene. Audiences sit in the uncomfortable aftermath of intense fights, of awkward moments, of the lingering pauses in between thoughts that are often edited out of theater and film. The result is a play that allows the viewer to learn just as much from the liminal spaces in between moments as they do from the moments themselves.

It is in moments such as these where audiences are allowed to watch the characters prod one another, grow in their understanding of themselves, and fully form. In the soft quietness of a tense yet not uncomfortable moment, Raheem asks Chotun if he wishes he spoke Bangla. In the bleary blue-black of another such moment, the audience learns of Pishi (Chotu’s uncle) and the relationship he carries on with a fellow online-billiards player, finding intimacy on the internet.

It is in many of these very same silent moments that the family learns the truth of their late patriarch, Chotu’s grandfather, whose sexuality and gender are never outrightly discussed, but whose appearance and manner of posing in newly developed photos are the subject of much discussion—or, perhaps, not enough—after Raheem finds an old roll of film in his camera.

The time and space of the play also allows for Chowdhury to wink at the title. During a conversation Choton has with Raheem regarding his work, Choton references Section 292 of India’s penal code, from which the play takes its title. He vents to Raheem that the material he’s gathering isn’t exactly fitting the narrative he was hoping to find. Instead, we see the enchanting Shou, who lights up the stage with their presence, and from whom Choton—and, by extension, the audience—learns more about India’s historied hijra culture.

As a result, the play feels revelatory by simply uplifting this aspect of queerness in India, rather than merely focusing on homophobia, highlighting an important truth; queerness has always existed, and continues to exist, despite what law or societal discussion might have to say about it.

It is not only the runtime that aids in pulling audiences across the globe and into the family’s home in Kolkata. From the moment viewers step inside the theater, they are brought within the sensory world of the play, with Indian commercials playing on a screen before the curtain even lifts. Much of the show takes place on the first floor of the family’s home, in the same living room cum dining room cum bedroom. The stage becomes a home, with little touches like the Aquaguard filter (ubiquitous in all Indian homes), and the elaborate ritual of setting up mosquito nets before bed adding to the heightened sense that the audience is in the world of the play.

The show has plenty of subplots (Pishi recounts a dream that is a film to Raheem and that is later screened for audiences; Raheem and Jitesh have scenes together in which much is said without much being said at all; Shou and Chotun have an enlightening conversation on a riverbank), but Chowdhury’s masterful direction keeps these tangents from becoming too overwhelming. The show itself is anchored by stellar, authentic performances by its cast, along with expert sound and lighting design that helps to focus the audience and further expand the world of the show.

Chowdhury does not infantilize the viewer by tying up all the loose ends of the plot and the character’s journey neatly in a bow by the end of the show. There are still plenty of questions that go unanswered and conflicts between characters that go unaddressed. Still, it feels right that the show ends in the way that it does, as it is easy to imagine the world of the play continuing beyond the ending seen on stage. And as Chowdhury leaves his audience to ponder the characters lives beyond the world of the play, he also leaves them with a sense of hope; the family evolves and grows, their understanding of one another has deepened, and so too, perhaps, has the audience’s of the world beyond them.

—Anjor Khadilkar is an Indian American freelance actor, director, and writer currently working in film/television and theatre. She is passionate about working to uplift marginalized voices and is interested in utilizing art and creation to create deeper cultural understandings. She is based in NYC.