Please Stop Mistaking “Parasite” as an AAPI Film

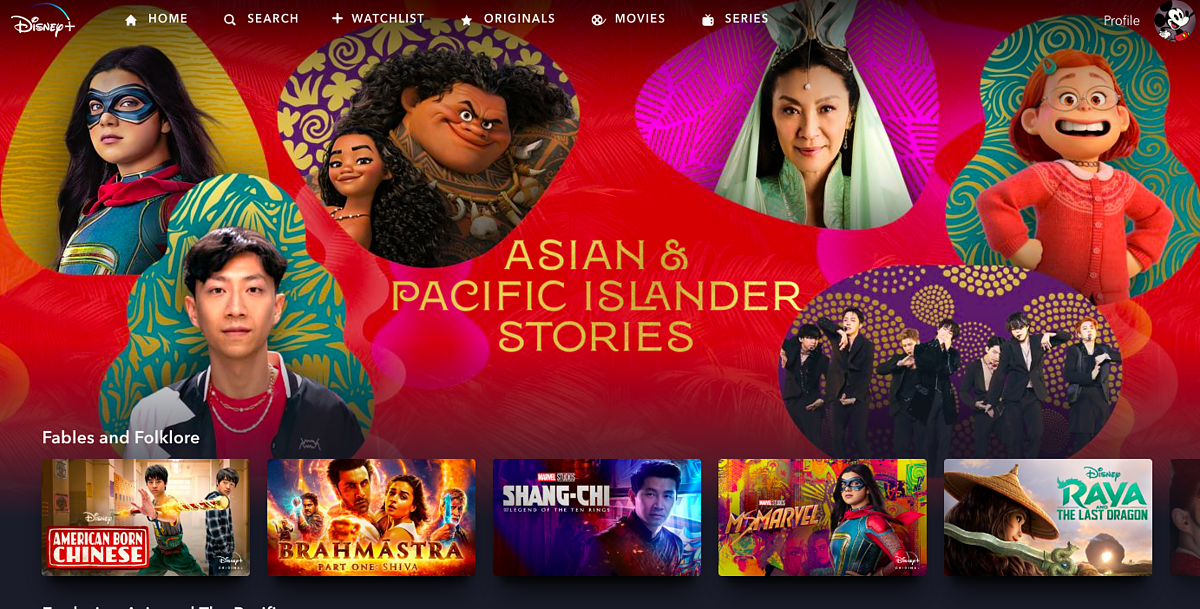

When the South Korean boy band BTS was invited to the White House to speak out against Asian hate for AAPI Heritage Month back in 2022, it struck me as a bit odd. While discrimination against Asians is certainly not exclusive to the US, I couldn’t help but wonder why the White House didn’t invite an AAPI artist to speak to the issue. There is certainly no lack of talent to choose from, and the whole point of AAPI Heritage Month is to bring awareness specifically to Asian American and Pacific Islander experiences, history, and culture.

The odd platforming of the Korean megastars during AAPI Heritage Month underscored something I have been noticing in AAPI representation for a while, especially prevalent in May. While there has been much to celebrate surrounding our representation in recent years with the runaway success of films like Everything Everywhere All At Once, and television series such as Never Have I Ever and Beef, I keep noticing that articles, streaming platforms, and events celebrating AAPI in film and television also often include media from Asia and the broader Asian diaspora.

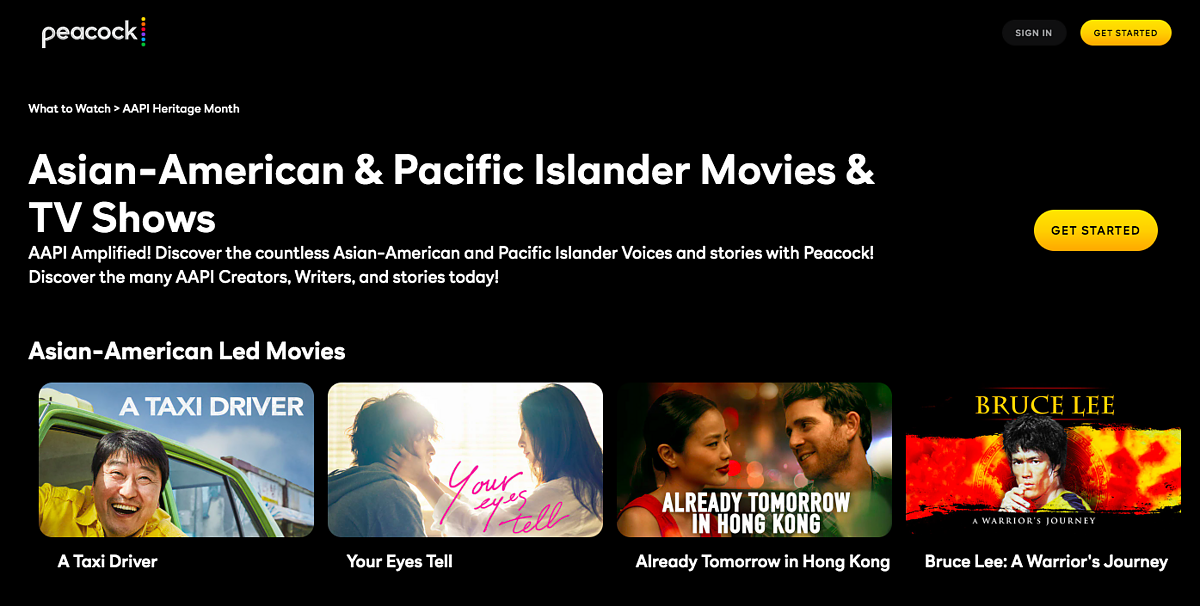

Lists ostensibly celebrating AAPI stories inaccurately include films like Slumdog Millionaire, Parasite, and Bend it Like Beckham, as well as Korean and Taiwanese television dramas. In one article celebrating films for AAPI Heritage month published this year by A. Frame, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ magazine, many of the films highlighted aren’t from the US at all. Titles include Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, In the Mood for Love, The Handmaiden, and Drive My Car—films from Thailand, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Japan, respectively. The “American” part of AAPI seems to disappear in the distinctions.

This issue is hardly endemic to film and television. A recent AAPI issue of Billboard had Peggy Guo—a South Korean-born, London-raised, and Berlin-based DJ and producer—as its cover star. The problem here is that these films and television shows are not about Asian American stories or experiences—they are about Asians either in Asia or in other diasporas. Each of these identities grapple with their own unique experiences and histories. While one may argue that there are some shared experiences that unite the whole of the Asian diaspora, these categories should be labeled more generally rather than specifically AAPI.

To lump together the entirety of the Asian and Asian diaspora’s experience under the AAPI label ignores and erases the specificity and distinct nature of not only AAPI identity but all other Asian identities as well.

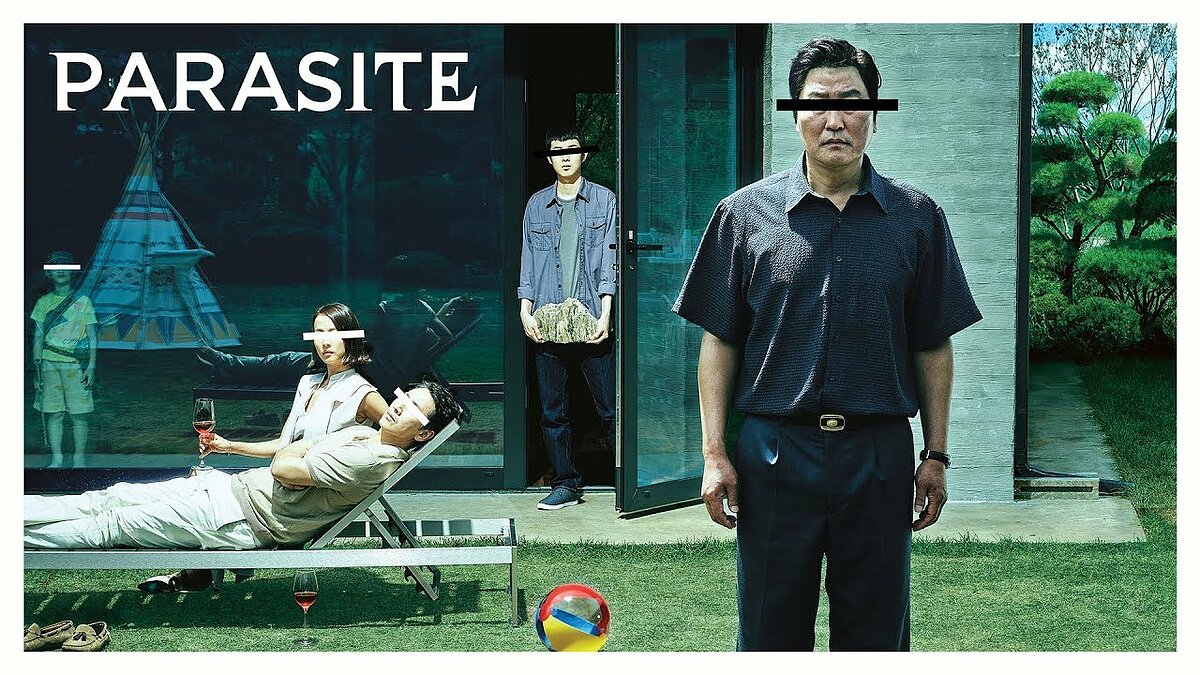

One film in particular that attracts this misattribution regularly is the 2019 Academy Award-winning South Korean feature film, Parasite. It depicts Korean characters played by Korean actors (with the exception of Choi Woo-shik, who is Korean Canadian), in a story set in South Korea, directed by Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-ho.

While the film is a crowning achievement for Korean cinema, it is certainly not an Asian American film. Parasite cannot be chalked up as an AAPI production making landmark strides in Hollywood. For starters, a film like Parasite does not fight the same battles that AAPI films do in the US.

Consider Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari, which portrays a first generation Korean American immigrant experience, written and directed by a Korean American filmmaker. Despite being a film produced entirely in the US about an American experience, Minari was categorized as a foreign-language film during the Golden Globes; a designation typically assigned to foreign films. The categorization also hinted at a larger, more insidious tendency of Americans seeing Asians as perpetually foreign, regardless of national identity.

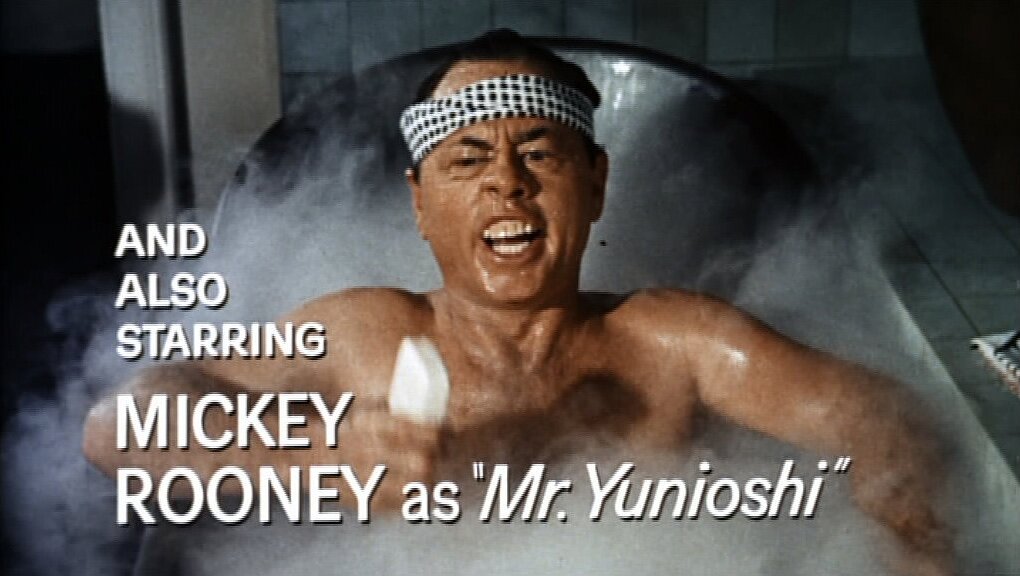

American media is still battling with racism embedded in an infrastructure constructed by decades of having a white male protagonist as the default lead character and casting white actors to play non-white characters.

When Jenny Han’s book, To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, was adapted into a feature film, Han reportedly had to fight to keep her protagonist Asian American. “The more alarming part of it was that people didn’t understand why that was an issue,” said Han in a 2018 interview with Teen Vogue. Author Kevin Kwan had a similar experience during the early phases of adapting Crazy Rich Asians for the silver screen. “They wanted to change the heroine into a white girl,” he told Entertainment Weekly. Filmmaker Lulu Wang was pressured multiple times to whitewash her characters in The Farewell. And back in 2002, Justin Lin had to max out his credit cards to make Better Luck Tomorrow because investors did not believe that a film with an all-Asian American cast would sell.

The AAPI community has also endured decades of abysmal onscreen characterizations. The blatant use of white actors in yellow, black, red, and brownface is deeply embedded in America’s media history. So is Hollywood’s perpetuation of Asian stereotypes—emasculated Asian men, martial arts-heavy characters, hypersexualized Asian women, and high-achieving model minority characters.

Asian Americans have had to deal with generations of cultural backlash from racist portrayals and characters like Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles. Prior to being cast in Everything Everywhere All at Once, actor Ke Huy Quan famously removed himself from acting for 20 years because of the lack of substantial, non-marginalizing roles available for Asian American actors.

While there is certainly a great deal to love and celebrate in media from the greater Asian diaspora, these works were not created within the same context as AAPI media. The increased globalization of streaming platforms, however, has further complicated these distinctions.

Titles like The Namesake, Pachinko, The Sympathizer, and Past Lives beg the question—how does one categorize a work if its cast, crew, showrunners, etc. have multiple nationalities? The Sympathizer, for example, is a mini-series by Park Chan-wook and Don McKellar, who are Korean and Canadian respectively. Its star, Hoa Xuande, is Vietnamese Australian. Its story, however,—an adaptation of a novel by the Vietnamese American writer Viet Thanh Nguyen about the Vietnam War—is canonically Asian American.

As streaming platforms such as Netflix, Disney+, Paramount+, and Amazon Prime Video aggressively look to increase the international reach of their content, this globalized approach to talent has become more prevalent. Amid this landscape, context becomes all the more important. Identifying and distinguishing AAPI stories as distinct from Asian or Asian diasporic stories is critical.

With the haste of content buying sprees, perhaps streamers neglected accuracy of content curation in the process. More cynically, however, it seems that the decision to lump Asian media within the umbrella of AAPI content has more to do with capitalizing on what’s already trending. Throwing a popular Korean TV drama into a curated content library or article seems to be aimed at the purpose of jumping on the benefits of the Korean entertainment marketing machine. As the diversity of content offerings has evolved, so should content curators’ understanding of cultural distinctions.

In the television adaptation of Gene Luen Yang’s graphic novel, American Born Chinese, Ben Wang portrays a Taiwanese American protagonist, Jin, who struggles to be seen as American in a predominantly white town. It seems even harder in the presence of new student Wei-Chen (played by Jimmy Liu), who arrives from Taiwan and inherently represents something foreign to Jin.

The protagonist’s desire is not just to be seen as one of the cool kids in high school, but to also avoid being seen as foreign by association. The coming-of-age narrative is not just about the struggle for identity and to fit in, but to be accepted as an American while being part of an ethnic minority, to be “one of us.”

Perhaps that’s the bigger, real-life caveat that needs to be unpacked offscreen. AAPI stories can be and are often multilayered in their national identity; such is the nature of diaspora. Celebrating the AAPI community is about recognizing both a specific and diverse American experience within a shared identity and political history—one that has historically been marginalized, underrepresented, and caricatured ad nauseam.

Labeling Asian media at large as AAPI reflects this historic lack of intentionality and consideration; at worst, it’s a symptom of tokenization. While the two identities are connected, they are certainly not the same. In this age of seemingly infinite options and possibilities when it comes to media, it becomes all the more imperative to be specific, recognized, and seen—authentically.

—Melissa Kim is a Korean American journalist and publisher. Her work has highlighted independent films, Asian American artists, and Korean talent at SXSW, Sundance, Tribeca, and the Hawai’i International Film Festival. Her articles have been published in NBC News, Character Media, and Koreanfilm.org. Melissa has an M.A. in Asian Studies; her graduate research has examined South Korea’s independent film movement and the impact of Korean television dramas on the American distribution market.