On Witnessing Art, Death, and Palestine

Lately, living has felt defined by the act of witnessing; in particular, witnessing death. For the last eight months, the world has witnessed the systemic genocide of the Palestinian people by the state of Israel—35,000 have been killed by conservative estimates, many of them women and children. Palestinians are being killed at such a rate, authorities cannot collect or tally all the names. There are mass graves and no obituaries.

Terms like genocide can be a double-edged sword; how can something as incalculable as mass, intentional killing deserve a name? How can a word hold the weight of so much loss, so many individual lives cut short?

Witnessing this while grieving the recent, sudden death of my mother has left me utterly raw. When she stopped working at a nail salon after 25 years because of cancer, she said to me, “I am so happy to not be working!” I will never forgive a system that afforded my mother a break only when she could not work.

It seems I have always marked my life through death. A few days after my family arrived in the United States, Jackie O passed away. I was only seven but sensed a palpable sadness when grown ups clicked their tongues with sympathy. To them, Jackie O, who was forever connected to JFK, represented the American Dream that they had come here looking for. The deaths of Princess Diana and Mother Teresa felt like the end of a kind of mythic goodness. I remember being in awe of Diana, who I knew to be a humanitarian, fashion icon, and a feminist. I proudly named myself after her when urged to choose an English name.

The recent death of artist Yong Soon Min was symbolic in that same way. While reading her obituaries, I hoped that her death, or a reminder of her life, would serve as a rebuke to the Asian American community. We find ourselves in a world where Asian and Asian diasporic art and culture has become immensely profitable. But because of that, I worry that the choices we make involve turning away from the community building and activism that Min saw as an indisputable part of living.

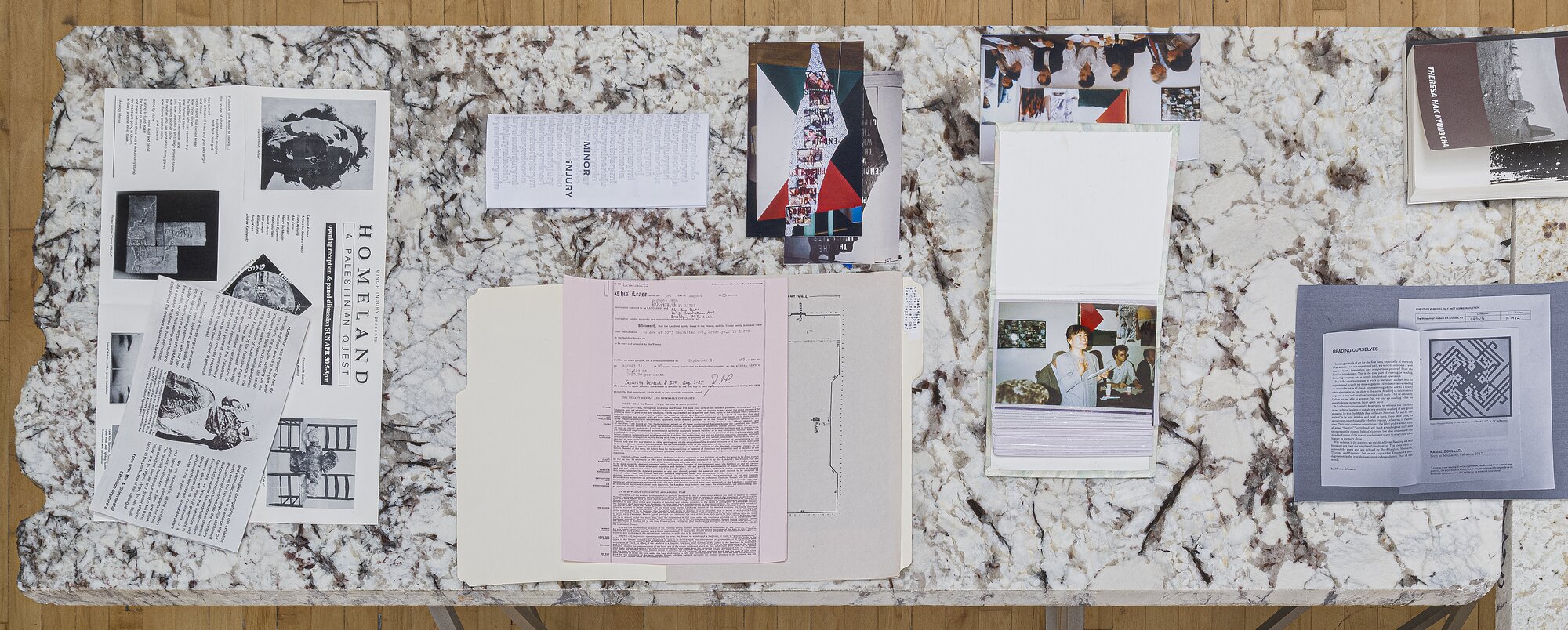

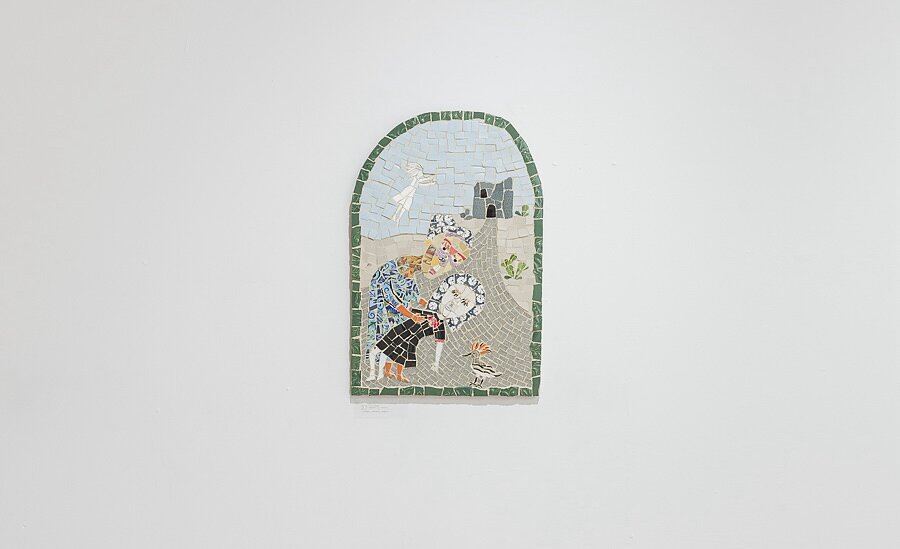

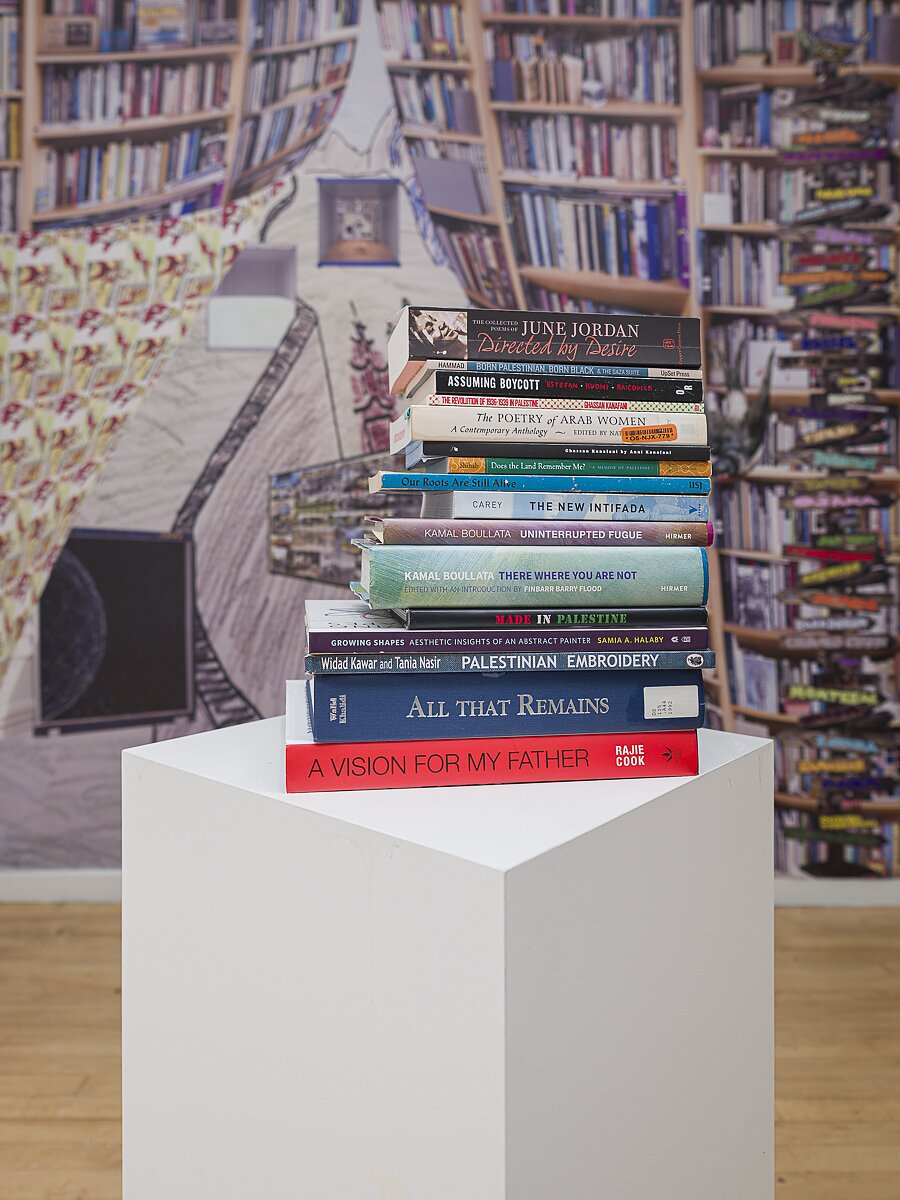

The exhibition “Moving towards Home: Art for Palestine in New York City 1989 & 2024” curated by Jenna Hamed and Amy Kahng at Subtitled NYC for me represents the kind of homage that I would like to see more of. As its title implies, the show revisits a 1989 exhibition, “Homeland: A Palestinian Quest,” organized by Min and Shirin Neshat at Minor Injury—a small Korean American-run space in Greenpoint not entirely dissimilar to Subtitled. In the current iteration, half of the gallery features works by Min, Neshat, and Betty Kano from the original exhibition while the other half displays works by Palestinian American artists Kamal Boullata, Haifa Bint Kadi, Fares Rizk, and Xaytun Ennasr, who were or are currently based in New York City. Between them is a display of reference books and archival material like photographs from Min’s trips to Palestine that visitors are encouraged to peruse.

Min’s Mneumonic Journey (2018), a large digital print on canvas that covers an entire wall of the small gallery, could easily overpower the rest of the works on view. Being that the work replicates Min’s personal library containing literature on art, theory, and activism, the work instead appears to host and make space for the other works in the show. Placing Min’s work in this way seems like a generosity on the part of the curators to honor Min’s spirit, regardless of how successful the original 1989 exhibition may have been.

Hamed and Kahng’s revisiting of “Homeland” is not an attempt to overly lionize the 1989 exhibition; it’s worth noting, for instance, that there were no Palestinian artists included in that show. “Moving towards Home” reminds us of the repetition of history, ongoing struggle, and a striving towards inter-communal solidarity. That the 2024 exhibition is titled after poet and activist June Jordan’s Moving towards Home (1982) is telling of the curators’ pursuit of turning the act of remembering into an active act of witnessing.

April 30, 2024

I take the subway to Subtitled NYC, a gallery in Greenpoint—or as founder Jaejoon Jang said to me with a chuckle, “a project space.” I’m here to see an exhibition that will open later this evening. I pre-arranged a walkthrough with co-curators Jenna Hamed and Amy Kahng timed early enough to miss the opening. I professed my disdain of openings to my friend V before heading here— “You cannot see the art, you have to say hi to people you don’t really know.” V permits my vain cowardice and responds graciously, “Yeah, I totally get that.”

April 30, 1989

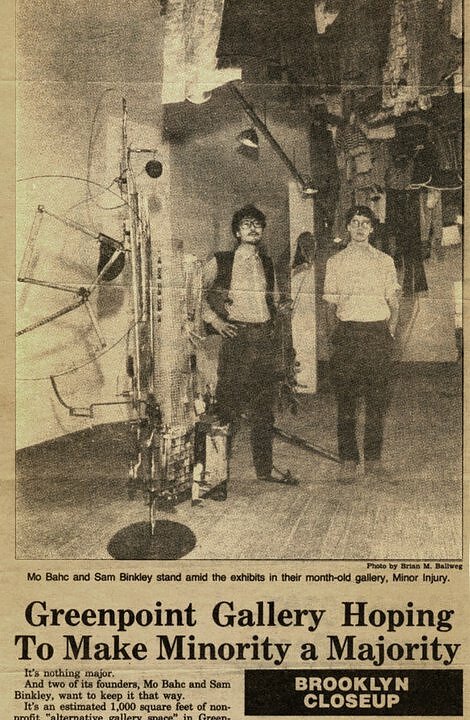

An alternative gallery space in Greenpoint called Minor Injury, founded by Mo Bahc and Sam Binkley opens a show called “Homeland: A Palestinian Quest” organized by artists Yong Soon Min and Shirin Neshat. The exhibition brochure says their “motivation for organizing this exhibition and panel discussion is to enlarge the currently small but expanding circle of informed and concerned contributors to the necessary dialogue which can begin to break down the barriers of prejudice, fear and disinformation.” The panel discussion includes Palestinian representatives, Israeli artists and several local artists who recently toured the occupied territories and Israel, sponsored by the Alternative Museum. The brochure lists 25 artists participating, none of whom are of Palestinian descent.

April 30, 2024

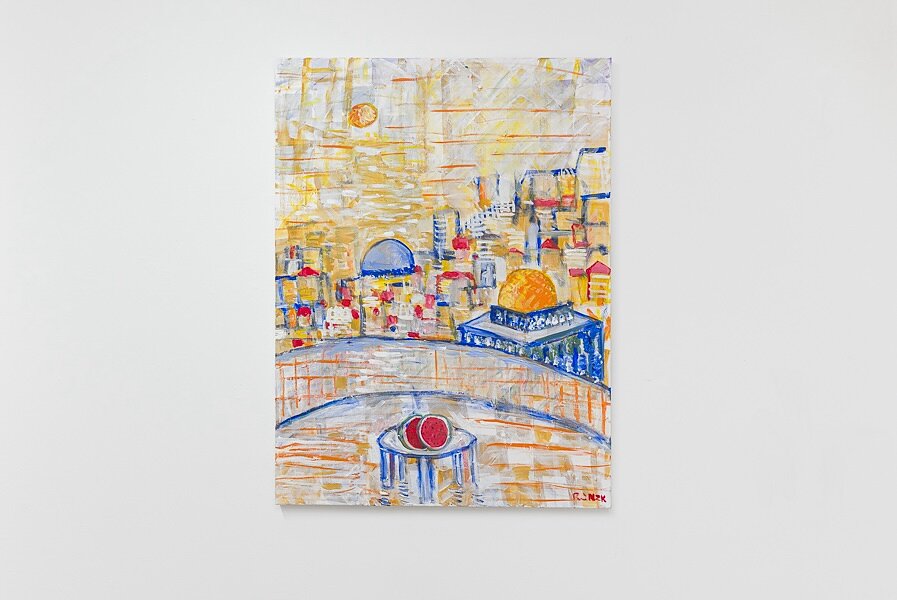

The exhibition is titled “Moving towards Home: Art for Palestine in New York City 1989 & 2024.” Unlike the 1989 show from which it draws inspiration, this exhibition does include work by Palestinian artists. I walk straight towards a work on paper by Kamal Boullata. A sun, an outline of a hill, a figure lying on the foreground. Her body seems to both cause and reveal flowers growing on the field. Or is it the flowers that reveal a figure that is of this land? Boullata only renders the figure’s face and delicate hands that seem to grip, pinch, or caress the ground beneath. Her body trails off to what looks to be an angel– “She must have died,” I deduce. The ripples caused by her body pressing against the ground transforms into waves that give her soul mobility.

This is the first spring after my mother’s passing. As I lie awake in the dark that evening, I think about my mother’s beautiful face looking at me through FaceTime–I thought seeing art, veiled as being “part of my job,” was a justified break from being with her sick body. “She bit her tongue so hard last night from pain,” my father said. Her lips, with a crust of dry blood, and me telling her on the phone as she nods or moans, “I will come see you after I pick up Mark from school.”

Unable to resist salving my pain with distraction, I reach for my phone:

Police Officers Stormed a Columbia University Building Occupied by Pro-Palestinian Protestors.

April 30, 1968

University Calls in 1,000 Police to End Demonstration As Nearly 700 Are Arrested and 100 Injured; Violent Solution Follows Failure of Negotiations.

—The Columbia Daily Spectator

March 18, 2024

Jaejoon is a tattoo artist I was introduced to through my friend R. I heard he also runs a gallery in Greenpoint, fully funded through his tattoo work. Lying there with my left arm in his grip, I feel obliged to ask him what will be up next in his space. He tells me in Korean that he always loved the artist Mo Bahc (later known as Bahc Yiso) and that in 1989, Bahc hosted an exhibition in his gallery, Minor Injury, curated by Yong Soon Min and Shirin Neshat about the Palestinian liberation. “I am holding it lightly,” he says. “If it works out, I will let you know,” to which I say, “Please do.” Jaejoon presses his tattoo needles into my flesh, outlining the canna lily that represents my mother.

Our intention is to provide exposure for artists who are suffering from differences of culture and language, false expectations by the majority, intimidating nature of the New York art world and Isolation. – Minor Injury

March 27, 2024

From “Remembering Yong Soon Min, A Pioneer of Asian American Art” by Nora Choi-Lee:

The New York Public Library in Flushing commissioned her to work on their building. She used frosted etched glass to create beautiful flowers that were embedded into the stairs leading into the library. The flowers extended into the children’s wing. We lived in Flushing at the time and I remember taking my young daughter Shannon there, thrilled to be walking on the steps that Yong Soon had beautified.

It was such an act of generosity and compassion to provide the majority immigrant community who lived in Flushing the luxury of being able to walk on frosted flower petals to enter the library. It gave the weary heart a moment of joy and enlightenment, of lightness and otherworldliness, for just the length of the steps into the library. I recall feeling giddy that I knew the person who had brought this joy into the lives of so many. I was so filled with awe and pride. It was one of the first times I felt the power of art and its effect on our lives.

January 26, 2018

Translated from Korean, my mother’s journal:

Jeonbuk, Muju County, Mupung-myeon, Hyeonnae-ri 1124

This is the address of my home where I was born and grew up.

It has been so long since I’ve written it.

In our house each year, when it was season, a red canna lily bloomed. Tall, with wide leaves – whenever the canna lily grew taller than the walls around our yard, flaunting its height, I felt so much joy.

My childhood home, still so vivid in my memory. When could I go there again?

April 30, 2024

There is another sun and horizon in the work by Xaytun Ennasr, Shrine for the Steadfast (2024). It is composed of two watercolor and ink drawings hung as a pair with two levels of shelving below them. The first holds ceramics containing olive and za’atar branches and the second supports booklets containing a segment from Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s “Praise of the High Shadow.” The suns depicted in the two watercolors are both golden yellow, but the undulating hills and land are composed of segments, the sections reminiscent of dry earth in a desert, except these patches are jewel toned.

As my eyes trace and travel through the deep maroons to blues to dark emerald greens, Ennasr’s introduction to Darwish’s poem echoes—

First I thought these landscapes were portraits of a trans Palestinian traveling between night and day within her body. I now realize that they are a portrait of all Palestinians traveling between night and day within our revolution. Of us an extension of our hills, valleys, springs, rocks, soil, sun, sky, sea, and river. We know this to be true every time our blessed resistance chants “We shall remain as long as olives and za’atar remain.”