Pao Houa Her’s Elusive Illusions at Baxter Street

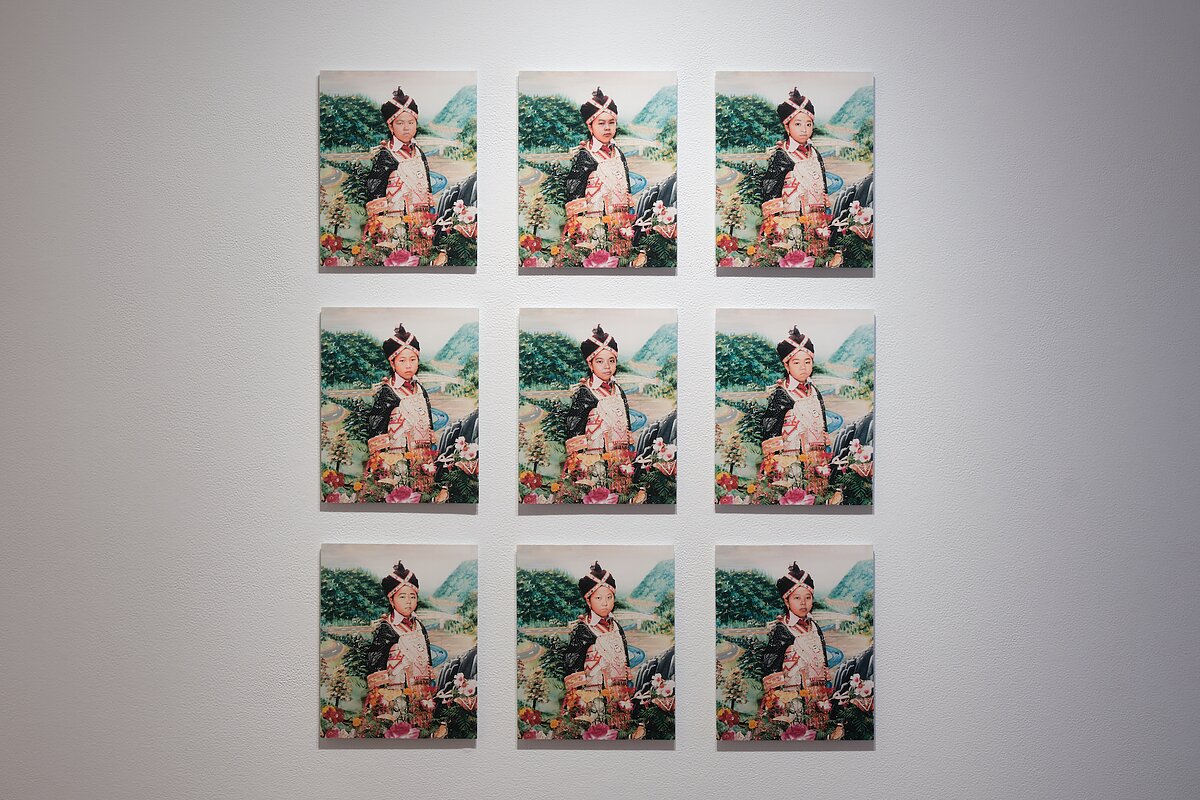

At Baxter Street at the Camera Club of NY, a polyptych from Pao Houa Her’s exhibition, “And Other Illusions”—on view from February 7 to March 20—greets viewers with nine iterations of My grandmother’s favorite grandchild (2017). Each of these staged portraits, replete with a painted backdrop and floral foreground, features the face of a different titular grandchild wearing the same headwrap and appliquéd outfit.

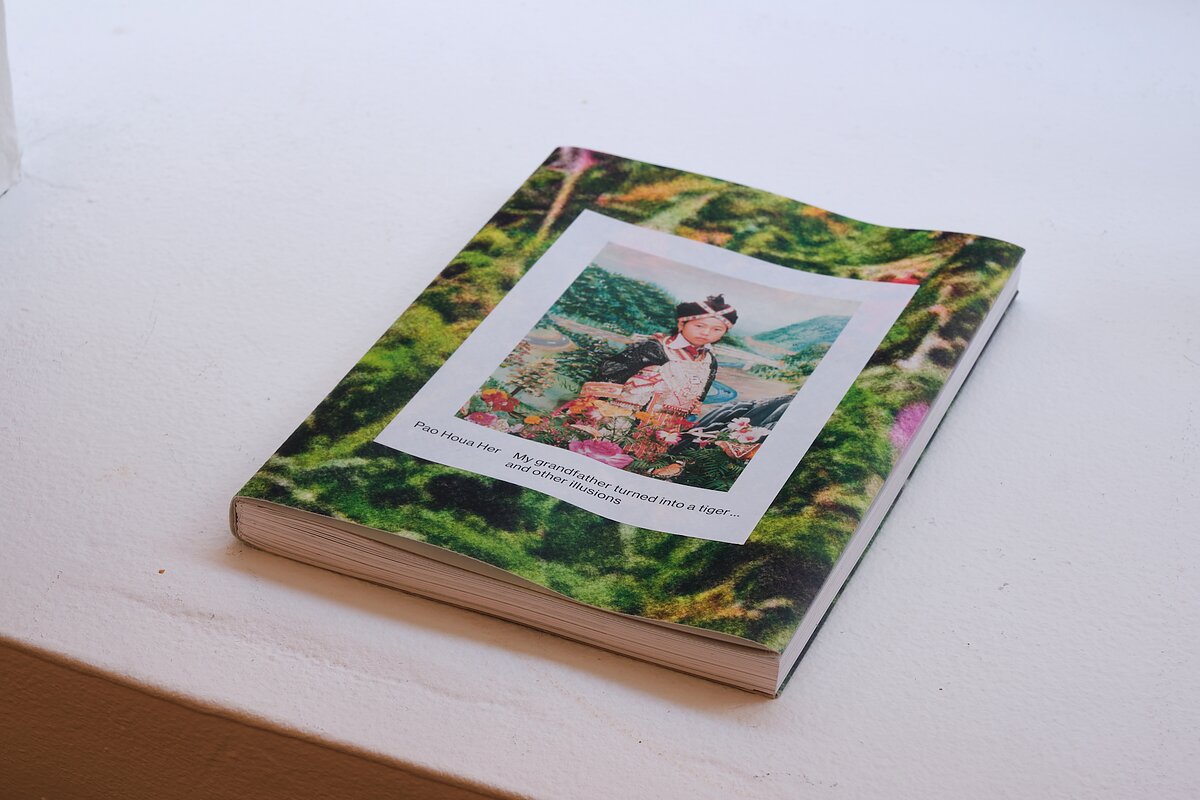

One of the grandchildren, Pao Sao, also adorns the cover of Her’s accompanying monograph, My grandfather turned into a tiger … and other illusions (Aperture, 2024). Each cover features one of 32 different blurred landscapes on its jacket, upon which the portrait is overlaid. These productions of subtle multiplicity and fungibility exemplify how Her makes illusions out of photography.

Playing with varied visual fields, the works presented in “And Other Illusions” highlight the ways in which landscapes and backgrounds at once disguise or disappear subjects while also making them hypervisible.

By introducing ecological elements from each image’s background into the foreground, Her meddles with the boundaries between subject and landscape. In Rest stop in Laos (2017), a black and white photograph of young men taking a selfie outside, the reversed camera phone figures the visitors as subjects, contrasting with Her’s long shot that places them within Laos. Meanwhile, in Untitled (Brian with fake flowers standing near the burn) (2019), an indoor color photograph centered on a figure holding a vase of fake flowers obscuring their head, the adjacent burn on the wall comes to stand in for the missing face.

At times, the landscape also appears as the subject itself—as in the lightbox of untitled (2021-22), a black and white photograph from California’s Mount Shasta, where Hmong American populations have transformed arid land into marijuana farms.

Her’s photos both recall and estrange the landscape of Laos, a country that many Hmong had once called home before their compulsory expulsion to the US in 1975. In the portrait Bee behind plants (2017), a woman clad in a tan hoodie sporting the word “ARMY” stands amidst a towering houseplant. The figure in the portrait evokes a history of Hmong conscription by the CIA to fight in US proxy wars in Vietnam and Laos. Familiarity with the wild jungles of Southeast Asia deemed Hmong fighters invaluable to US counterinsurgency efforts, while also rendering them inscrutable as US citizens in its aftermath.

The incorporation of plantlife alludes to this racialized history and ontology as Her captures mercurial subjectivities produced under tropical canopies. Flirting with the genres of portraiture and landscape photography, Her’s photographs emphasize the illusoriness of staged authenticity in visual culture. “And Other Illusions” draws from a range of Pao Houa Her’s photographs to picture, and thus to imagine, imperceptible histories and homelands. By crafting illusions, Her wrests the colonial technology of photography from its fraught usage and past in order to weave diasporic tales of loss, inheritance, and desire.

—Jacinda Tran is a writer, researcher, and teacher based in Lenapehoking (Brooklyn, NY). She is currently a postdoctoral fellow in Global American Studies at Harvard University, where she is working on a book about visual technologies and imaginaries established during US intervention in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.