Vivien Sansour Plants Seeds of Hope for Palestine

On a hillside overlooking the Hudson River, thousands of small white flags are planted in the frosty ground. Written on each is the name of a person who has died in Gaza as a result of the ongoing Israeli siege. At the time of this writing, the death toll is estimated to be at least 18,000.

“In Palestine, we bury our seeds in ash,” said Palestinian American artist and researcher Vivien Sansour, beckoning us to take a handful of soil and a packet of seeds. They are rose winter radishes, an heirloom from Palestine from her ongoing project, Palestine Heirloom Seed Library. “I invite you to bury with it the parts of you that are willing to accept this mediocrity.”

Organized by Sansour along with a group of faculty, staff, students, and community members at Bard College on a recent Friday afternoon in December, the symbolic funeral brought together nearly a hundred mourners to the campus’s Blithewood Garden to affirm life and hope in the face of suffocating death and destruction.

In the ten weeks since Hamas’s deadly October 7th attack on Israeli citizens, the Israeli government under the leadership of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has unleashed the equivalent of two nuclear bombs on Gaza.

Civilians make up 61% of Palestinian casualties; more civilian casualties than any other conflict in the 20th century. Eighty percent of Gaza’s 2.3 million people have been displaced. Over 7,500 Palestinian children have been killed. An estimated 25,000 have been orphaned. Leaders of some of the world’s largest global humanitarian organizations have said that they have seen “nothing like the seige of Gaza.”

Sansour was born in Beit Jala, a town just outside of Jerusalem in the West Bank. She remembers growing up in a tight-knit, vibrant community, where people took care of one another and lived with the seasons. “The trees informed us about our activities,” she explained. “My whole life has been an attempt to return to a life I already had; a life that I didn’t appreciate as much as a child. I didn’t know it would be destroyed.”

While staying in Jerusalem in 2014, she found herself unable to find many of the foods that she once enjoyed in abundance growing up. Since the Six Day War of 1967, Israel has systematically suppressed Palestine’s once thriving agricultural industry via land confiscations, permit restrictions, and limits on water supply and production—to say nothing of the effects of airstrikes on the land. This has resulted in a Palestinian population that has become largely alienated from their own Indigenous foodways, dependent on foreign and Israeli imports.

Along with fellow Palestinian diasporic artists like Jumana Manna and Amanny Ahmad, Sansour sees food and agriculture as a way to affirm Palestine’s living history, culture, and resistance. “Food is extremely political,” she asserted.

One particular plant Sansour craved while in Jerusalem was jazar ahmar, a Palestinian purple carrot that is typically stuffed and cooked in a tamarind sauce. The resuting dish is called jazar ahmar mahshi bil tamr el hindi. “It was one of my favorites growing up,” said Sansour. “My mother used to make it all the time.”

In just a few decades, jazar ahmar, along with many other plants native to the region that constitute Palestinian identity, heritage, and a sense of home, have nearly disappeared from the landscape. It was with this realization that Sansour began her project of saving these precious fugitive seeds.

“One seed at a time, I recovered another story and discovered another part of my heritage that had been dismissed and brutalized,” said Sansour. “I wanted to serve the seeds. People think I’m saving seeds but really, the seeds have been my savior. These tiny beings were and continue to be a reminder that as much as you try to erase yourself in order to fit into mediocre structures, they are here to remind you that you are something better.”

Along with jazar ahmar, baladi tomatoes, Jadu’I watermelons, and yakteen gourds are among the 47 heirloom varieties that can be found coated in ash and stored in jars at Palestine Heirloom Seed Library’s physical space in the ancient village of Battir.

The library is housed in the second floor of a traditional hawsh style home, whose design dictates its rooms surround a central courtyard. According to Sansour, one will often find farmers and locals in this common area drinking tea, exchanging stories, and relaxing—“It’s an open space for people to come in and out.”

This porous philosophy is echoed in the ethos of the seed library. Unlike most other archives, Sansour does not make it a point to keep record of who is taking seeds or where seeds are being planted. “Palestinian Heirloom Seed Library really lives in the fields of farmers,” she explained. “I don’t track the seeds; they become a part of people’s lives. I wanted the seeds to stay free. They don’t belong to me, they belong to themselves.”

“For me, the seed library isn’t just about seeds; it’s a journey of reclaiming our imagination,” Sansour continued. “I don’t want a free Palestine that will become another nation state that oppresses other people. That is not what I’m fighting for. I want a Palestine that is truly free and breaks the cycles of history.”

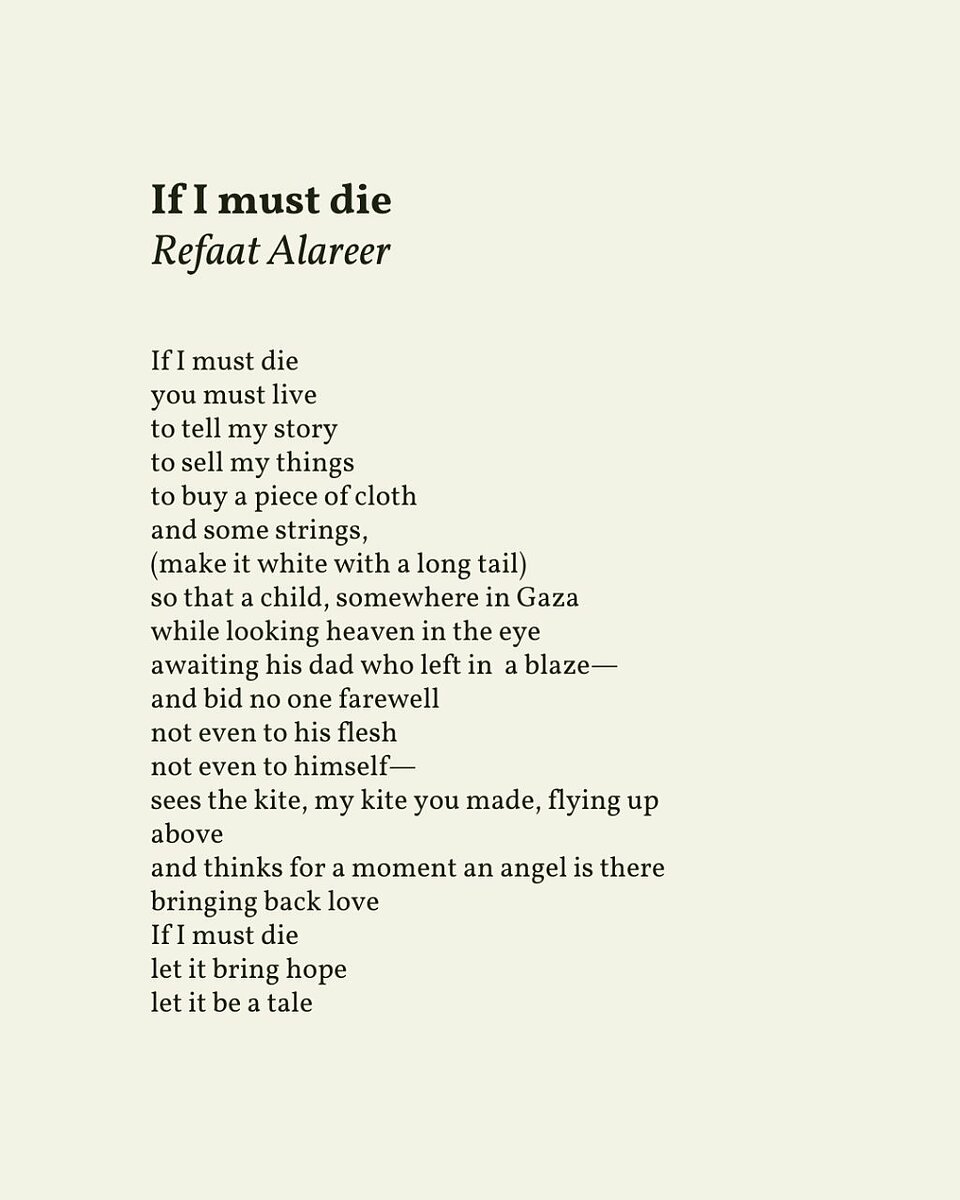

As the sun began its descent behind the Catskill mountains, reflecting its radiant light against the Hudson River, a student read aloud a poem by the renowned Palestinian poet, academic, and educator Refaat Alareer. The poem, originally written in 2011, was re-shared by Alareer in early November in anticipation of his own death. He was killed in an Israeli airstrike on December 7th.

Cascading down into the valley, Alareers words rang somberly:

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale

As we gathered to collect seeds, Sansour left us with an invitation to consecrate the ritual of our planting. “When you plant your seeds,” she urged, “think of the people of Gaza. When you eat what grows, let them become a part of you.”