“Offerings for Escalante” Traces the Webs of Labor, Resistance, and Ecology

On September 21, 1985, the 13th anniversary of Ferdinand Marcos declaring Martial Law in the Philippines, thousands of protestors gathered in Escalante, a town on the island of Negros. Colloquially known as the sugar bowl of the Philippines, Negros had experienced years of famine under the Marcos administration’s attempt to monopolize and control sugar production.

What was supposed to be a peaceful protest against the impoverished living conditions created by the government became the site of a state-sanctioned massacre when policemen opened fire on the crowd, killing 20 protestors. These events and their resulting social, political, and ecological reverberations serve as the subject of “Offerings for Escalante,” an exhibition by artists Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien, currently on view at MoMA PS1 through February 17.

Entering the exhibition, visitors are enveloped in a carousel of diaphanous projections cast by onion skins in Study for Compost Light (2022). Reminiscent of organisms on a microscope slide, these organic shapes appear again across the main work featured in the exhibition, a film titled Langit Lupa (2024). Weaving together survivor testimonies and original documentary footage from the island of Negros, the film features the shadows of plants created by phytography, a method which uses the internal chemistry of plants to develop images. The spectres inch across the screen, obfuscating the survivors as they recount their experiences. Slotted in between these testimonies, the film follows a troupe of children who play tag in a public cemetery and traipse across the cemetery’s surrounding sugar cane field.

In the film, children’s play turns to offertory procession as they re-enact a people’s mass that Camacho witnessed during his months researching in Negros. Organized by a coalition of survivors’ families, the original people’s mass was held in lieu of the traditional anniversary re-enactment of the Escalante massacre, whose yearly occurrence has been blocked by the government.

As they weave through the gravesite, each child holds an object in their hands—a stalk of sugarcane, a net, a book—each representing a different sector of labor that came together in protest in 1985. An offering, much like a re-enactment, ushers in a collapsing of time through its ritual rehearsal of memory. A surviving mother to a 14-year-old victim of the Escalante massacre states, “Every September for the anniversary, I am there”, about the annual re-enactment, despite the personal pain and guilt the event elicits. Her devotional adamance, perhaps, is a response to the ongoing oppression of Negros by the Philippine government—that her daughter’s memory and sacrifice not be taken in political vain. Here, ritual rehearsal reconstitutes into a ritual refusal. It is this process of political transformation and legacy construction that Camacho and Lien attempt to compound through their staging of this triplicate re-enactment. In Langit Lupa, the artists investigate the political potentials of mimicry. As writer and researcher Pablo Santacana López writes, “reenactors are capable of creating a new collective will.”

With “Offerings for Escalante,” Camacho and Lien expand upon their career-long experimentations in the role of artist as activist. This extends to the community art-based approach behind several of the paper works on view in the exhibition, which they co-created with children from Sagay, an agrarian community near Escalante which had undergone a similar farmers massacre in 2018.

Part of their ongoing series of “tangle works”, pieces like Flame garden (enzyme) (2024) incorporate handmade paper composed of organic materials drawn from Negros such as sugarcane fiber, cogon grass, and banana stalk. Camacho and Lien then refashion the paper they collaborated on with community members, forging them into the form of a fire, whose flames stretch out toward delicate butterflies, their almost-translucent wings constructed of flower petals, seeds, and onion skin.

The works are meant to evoke an abundant livingness, a suggestion of the resilient native ecology still burbling beneath the oppressive, monocrop uniformity imposed by the hacienda agricultural system. Instead, enclosed in shadow box frames, the works feel resoundingly static, taking on the characteristics of a captured specimen—pinned down and suspended in time.

“Offerings for Escalante” finds Camacho and Lien wrestling with the positionality of the research-based artist. Key to their examination into the interstices of ecology, colonial history, agriculture, and labor, is a palpable awareness that what lies at the center of their research is a living, breathing, organizing movement. Occasionally, this awareness gives way to a political self-consciousness that colors their output. However, more compellingly, it also pushes the artists to search for solidarities.

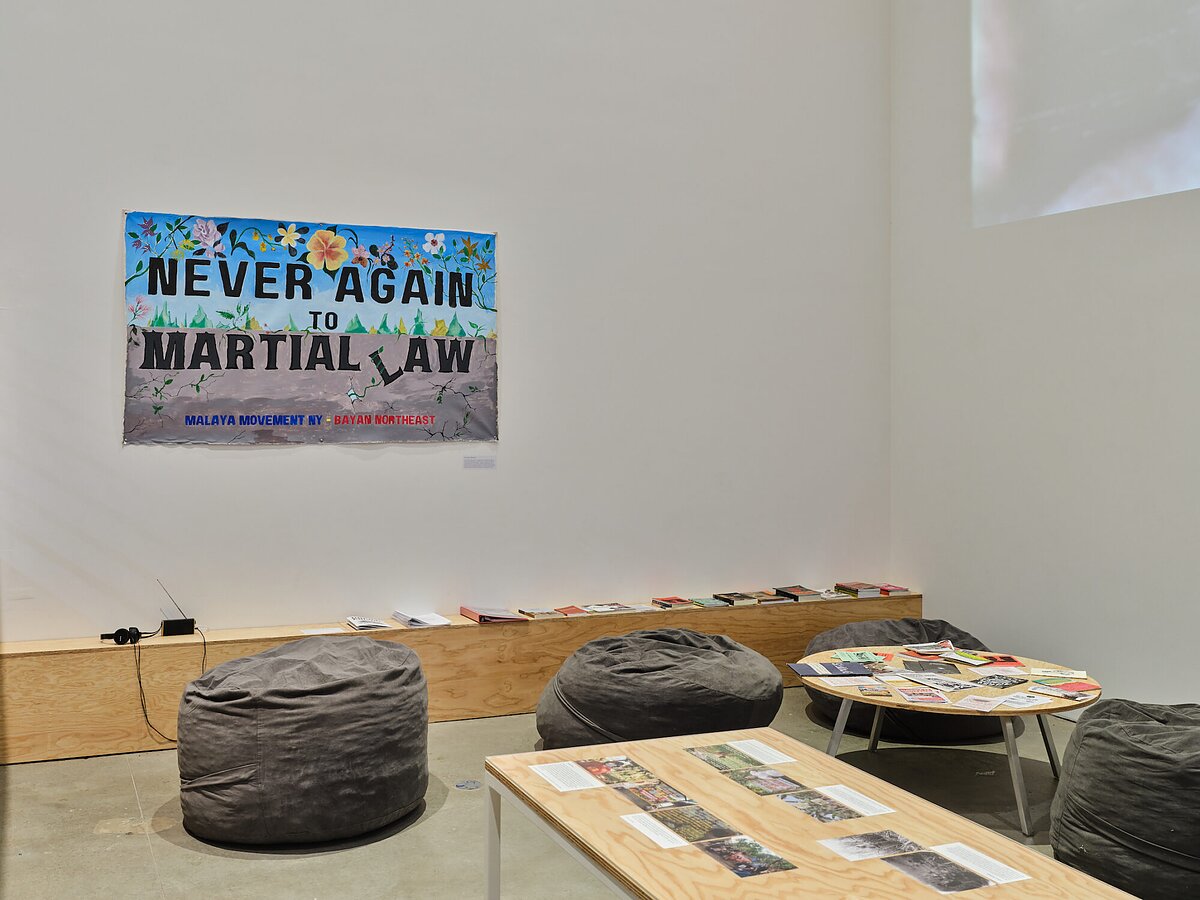

In the museum’s lower galleries, Camacho and Lien have partnered with activist organizations from the Philippines and New York to present a curated assortment of historical films, zines and books, as well as protest ephemera with the purpose of contextualizing the struggle for land justice in the Philippines. The duo, in a letter co-published with the organizers and community groups, explain that this portion of their contribution to the exhibition is to highlight cultural production that has sprung from and in service to the national democratic movement in the Philippines. Aligning their work with the liberatory efforts of the artists and cultural workers of the movement, they write, “For artists and writers of the ND movement, cultural work is merely one component of a larger organism tied to the needs and aspirations of the oppressed masses.”

—Isabel Ling is a writer, editor, and cultural critic based in New York City. Her writing on food, art, culture, design, and technology has been published in outlets such as Curbed, Vulture, Eater, The Verge, Frieze, Spike Art Magazine, and Hyperallergic.