How Migration Impacts the Mediums and Practices of Diasporic Artists

When I was getting ready to move from Seoul to New York, I spent several days selecting Korean poetry books to accompany me on my trip over the Pacific. These books were more than just collections of poems; they embodied my identity and memories, poised to be reinterpreted in a new context, on a different continent. Now, residing in my Brooklyn apartment, they offer a clear yet profound insight: migration is not solely about the movement of individuals from one place to another. It also involves the transfer of personal objects that anchor one’s sense of self in unfamiliar territories. This observation raises an intriguing question, particularly with regard to diasporic artists: how do memories and identities embedded in chosen mediums resurface and evolve in new environments?

Artists Ian Ha (b. 1997) and Khia Hong (b. 1994) both grew up between the US and Korea before eventually settling in New York. Their works offer a glimpse into how art practices resonate and transform with an artist’s geographical transitions. In Ha’s work, jangji—a type of hanji (traditional Korean handmade paper)—serves as a canvas where personal narratives intertwine with the broader discourse of painting. In the US, the narrowed cultural legibility and limited availability of jangji has provided Ha with a unique opportunity to deepen his engagement with painting. Meanwhile, Hong’s stone and plaster works examine the circumstances surrounding the creation of a sculpture, particularly from the standpoint of a young female sculptor. The differing physical and cultural environments of Seoul and New York influence not only Hong’s sculptural forms but also her identity within the discipline.

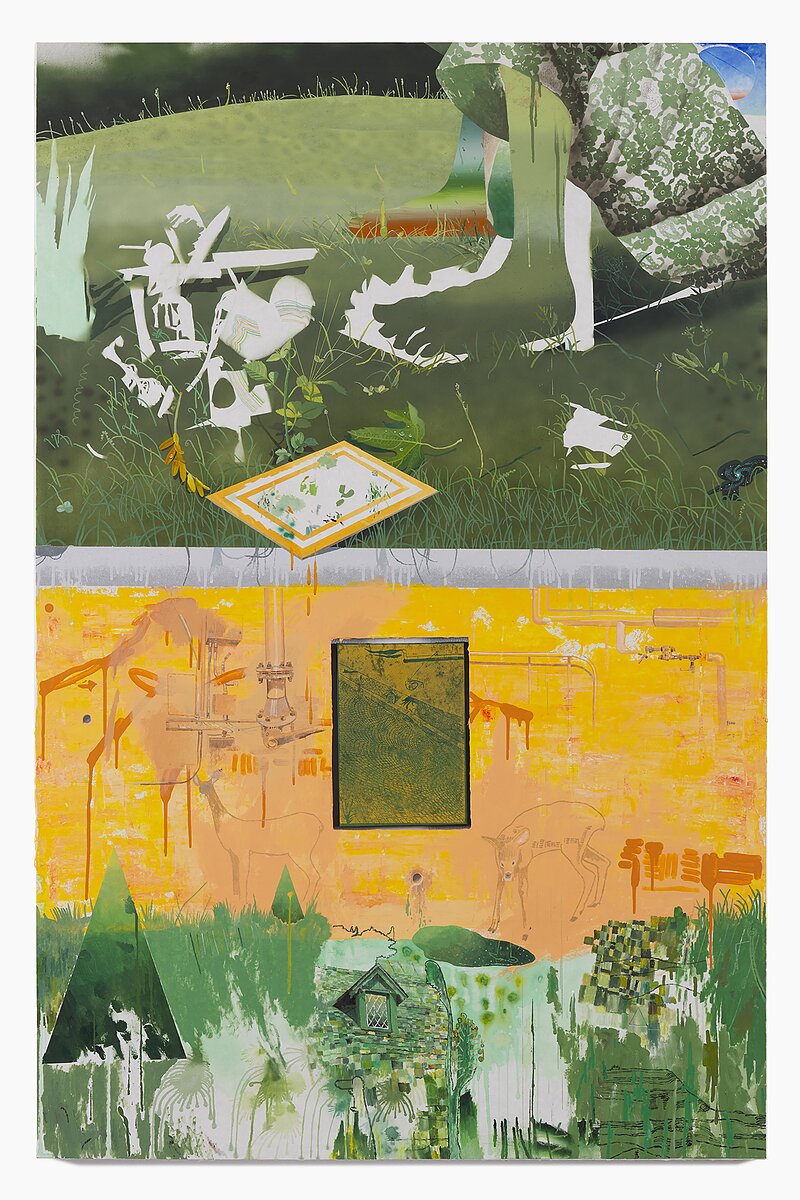

Similar to the way jangji’s absorbent properties allow for even color distribution, his paintings absorb and interweave a variety of art historical references from around the world, unfolding in a rich and nuanced tapestry. Educated in “Oriental Painting” in Seoul, Ha is also deeply influenced by artists like Charles Sheeler, James Rosenquist, David Hockney, and Matthias Weischer. Although these painters primarily worked with oil or acrylic paint on canvas, their explorations of perspective significantly shaped Ha’s work. Despite their diverse methodologies, each of these artists enriches Ha’s distinctive layering of memories and experiences, contributing to a multidimensional painting.

Ha’s efforts to reinvent painting by merging different traditions have grown stronger since relocating to New York. A prime example is his adoption of shaped canvases, moving away from the traditional rectangular formats to embrace circles and smooth contours. This period of experimentation was largely nurtured during his time pursuing an MFA at Columbia University, where he had access to facilities such as wood and metal shops—resources unavailable during his education in Seoul.

His move to New York has also reshaped his approach to printmaking. While his methods in Korea were exploratory and often deviated from conventional techniques, his experience at the LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies has fostered a more disciplined approach, emphasizing technical precision and strict adherence to established practices.

Ha’s paintings combine new forms and different techniques, encapsulating a personal journey that intertwines his past and present. These works foster spontaneous interactions with his past self and current identity, from Korea to the US. In this framework, jangji emerges as a crucial foundation, allowing Ha to engage in a dialogue with the medium of painting and with himself. However, obtaining this material in the US poses significant challenges. Ha imports jangji with the help of family and friends traveling from Korea, which not only incurs financial burdens but also necessitates careful planning of his workload.

Despite these obstacles, Ha remains dedicated to using the material. With his deep understanding of its unique properties, jangji is more than just a physical base for paint; it functions as a foundation that allows for more genuine dialogues and expressions in his art. This approach not only reflects his experience of growing up in diverse environments but also propels him toward the immediate expansion of his practice, situating his work as a profound exploration of memory, materiality, and the interplay among different painting traditions.

Hong’s process, thus, is intensely physical, recalling the labor-intensive practices of traditional sculpture that require meticulous selection and intricate carving. The sharply chiseled marks and glass-like polished surfaces in Hong’s granite or marble works reflect her profound respect for the resilience and meticulousness integral to this method of sculpture. Her approach extends beyond simple manipulation of materials; it is an exploration of the latent stories within each block, stories that unfold through her physical engagement with the medium.

Due to the nature of her work, which involves moving and handling massive, heavy materials, it is deeply influenced by the environment beyond her studio. During her time in Seoul, she was acutely aware of the challenges faced by Korea’s young female sculptors, including difficulties in securing assistant roles in studios due to systemic barriers and finding safe studio spaces. These economic and logistical obstacles are fundamental to Hong’s creative process. Consequently, her works are often named after places in Korea like Chuncheon—a city where she lived for two years because she couldn’t find a suitable studio in Seoul for her large-scale stone and plaster pieces. Hong’s sculptures, thus, are a tangible reflection of her personal experiences and the broader socio-political and cultural context in which she operates.

Following her move to New York, Hong’s artistic expressions have naturally evolved. Facing both logistical and financial constraints, she pivoted to using primarily plaster, a decision influenced by its cost-effectiveness and suitability for her limited studio space in New York. This choice not only met her budgetary and spatial needs but also opened doors for her to delve into a new artistic milieu. The nuanced perceptions of gender and ethnicity in New York, vastly broader than in Seoul, have also presented fresh challenges and opportunities for Hong to reflect on her surroundings and navigate her identity. Plaster, in this context, becomes a valuable tool for Hong, aiding her in conceptualizing and materializing her responses to these new, often abstract, influences without a predefined notion of her surroundings.

While Hong’s previous work with stone showcased meticulous cutting and detailed carving, aiming to realize a specific vision, her approach to plaster is more fluid and experimental, focusing on layering and addition. This method fosters spontaneity in her sculptures, allowing for a richer exploration of identity that moves beyond the binary contrasts of her past work. With plaster, Hong is adopting a more malleable and expansive sculptural language that mirrors the evolving dynamics of her identity and expressions. Her recent figurative plaster pieces are evolving in tandem with her sense of self.

Hong’s sculptures offer a narrative on the interplay between the artist’s internal conditions and external influences, encouraging viewers to consider not just the final form but also the complex societal, economic, and cultural factors shaping it. Her work thus serves as a multifaceted dialogue, intertwining reflections on identity with the broader context in which art exists.

When artists embark on diasporic journeys, their mediums traverse borders as well. These mediums, intertwined with the artists’ personal histories, cultural contexts, and the broader narrative of art history, undergo transformations that mirror the evolving identities of the artists. In the diverse milieu of New York, Ha’s paintings and Hong’s sculptures showcase a dynamic interplay between the artists and their surroundings. Both artists, through their distinct yet intersecting approaches, demonstrate that their mediums are not merely vessels of artistic expression but also mediators of memory and the migration experience.

Ho Won Kim is a curator and writer based in Seoul and New York.