CAO Collective Bridges Art, Healing, and Community

When the founding members of Chinese Artists and Organizers (CAO) Collective first came together in 2022, they were united by a desire for more nuanced narratives and approaches surrounding the expectations and production of Chinese and Chinese diasporic art. As a queer and feminist arts collective, they have since continued to cultivate sustainable and communal practices, bridging various marginal identities and bringing art into the center of their community-based activism.

Through poetry, performance, food art, photography, video, meditation, and installation, CAO’s work layers different artmaking practices to convey the nuances of communal expression and language. These interactions reflect themes of memory, ritual, and intimacy, often searching for methods of translation between intergenerational thresholds. Within their first year, they received a “What Can We Do?” grant from A4 which supported the inaugural performance of their ongoing work, The Ciba Punch, on September 4, 2022 at Sara D. Roosevelt Park in Chinatown, Manhattan.

CAO’s practice engages in physical, spiritual, and mental processes, and critically examines systems of discipline, censorship, and capitalist extraction to reimagine what a community can be when freed from those constraints. Call-and-response plays a particularly vital role in their practice, especially in their poetry workshops. At “to hold a we,” a group exhibition at Brooklyn’s BRIC, CAO Collective’s site-specific installations are a clear demonstration of how they utilize such interactions.

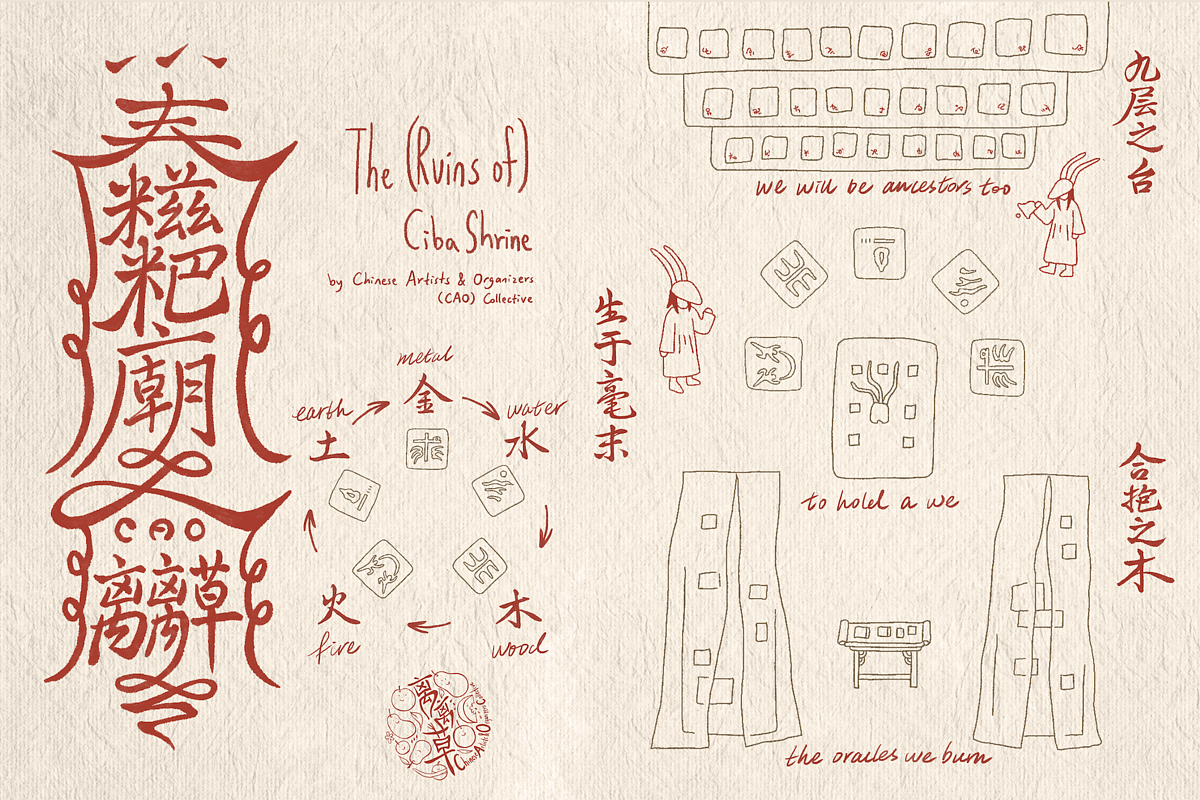

Exhibited alongside works by 14 other emerging and early career artists from the BRIClab residency program, CAO Collective’s The (Ruins of) Ciba Shrine is deconstructed into three site-specific, multimedia installations. The works draw inspiration from the tomb of Shang Dynasty female general and empress Fu Hao and Han Dynasty noblewoman Lady Dai.

Facing the altar is to hold a we, a fabric interwoven with spiritual bells that lay gently above a central mugwort cushion. The fabric is inspired by the silk banner from Lady Dai’s tomb, used in the “calling of the soul” ritual after death. Five kneeling cushions with designs inspired by the five elements of transformation in Chinese cosmology, engravings from buried bronze food vessels, and oracle bone writings from Fu Hao’s Tomb face the central fabric.

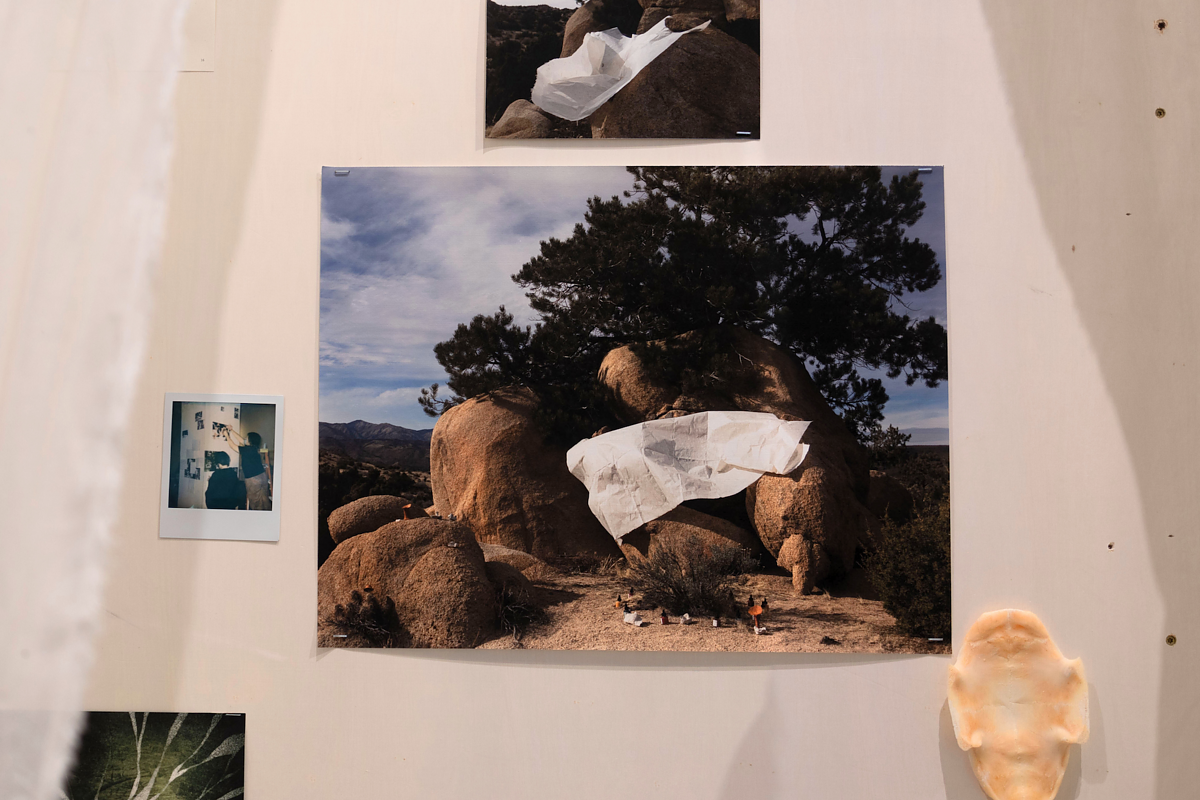

The final installation, the oracles we burn, stands behind the mattresses as two wooden columns covered in community poetry, photos, and drawings. Modeled after steles and couplets found at the entrances of shrines and tombs, the columns are “simultaneously a community archive and a passage into a space of collective memory and queer feminist myth-making”. Delicate yet resilient steamer cloths flutter over each column, protecting and obscuring the community within its embrace while simultaneously inviting onlookers to peek into moments of kinship and intimacy portrayed.

The Ciba Punch was performed on the opening night of the exhibition, merging all the mediums and themes of the three installations to transform the site into an active manifestation of collective dreaming, memory-making, and connection into ancestral pasts and communal futures. The Ciba Punch is centered on the traditional Chinese process of making ciba, a type of sticky rice cake. The act of pounding individual grains of rice into a merged final product exhibits the process of collective creation and the possibilities of communal experiences.

The performance was a culmination of mediums necessarily engaged in one another to produce a spatial experience that is neither grounded in the gallery space nor in the present time. It was both a ceremony and a ritual, offering a fleeting yet intimate space for kinship, care, and the possibility of collective dreaming, held by those from queer, disabled, diasporic, and marginalized communities.

—Hannah Zhang is a freelance arts writer based in New York City. She is interested in intersections of art, literature, and design, especially seen through the perspectives of Asian American identities. Her writing can be found in Art Observed and Ocula Magazine.