Artist Michael Wang Challenges Visions of Apocalypse as Ruin

Artist Michael Wang senses that there’s more to our world than what we can see; something just underneath the familiar, or perhaps right behind it: dispersed networks, lost geographies, ecologies both real and possible.

These specters have gone by many names. The eco-theorist Timothy Morton famously called them “hyperobjects"—entities like climate change or global markets that operate at scales so expansive they defy our very ideas of what an object can be. As Morton and similarly minded scholars have noted, avoiding the worst outcomes of the Anthropocene requires us to first learn how to properly apprehend these hyperobjects; only then might we successfully transform them. This, however, is no simple feat. Our perception struggles at these altitudes—they are too large, too ill-defined for our traditional modes of comprehension.

For the past decade, Wang has grappled with precisely this task as a conceptual artist. Tackling everything from microscopic viruses to the inter-continental trade flows, Wang has consistently been guided by a deep attunement towards the unseen histories, connections, and lines of force that shape us. Confronting his pieces, one can’t help but feel that they’re at the precipice of a monumental presence whose edges far exceed our horizons. It can be dizzying, but as you sit with these works, you slowly begin to sense it too: all those invisible worlds that lie before us.

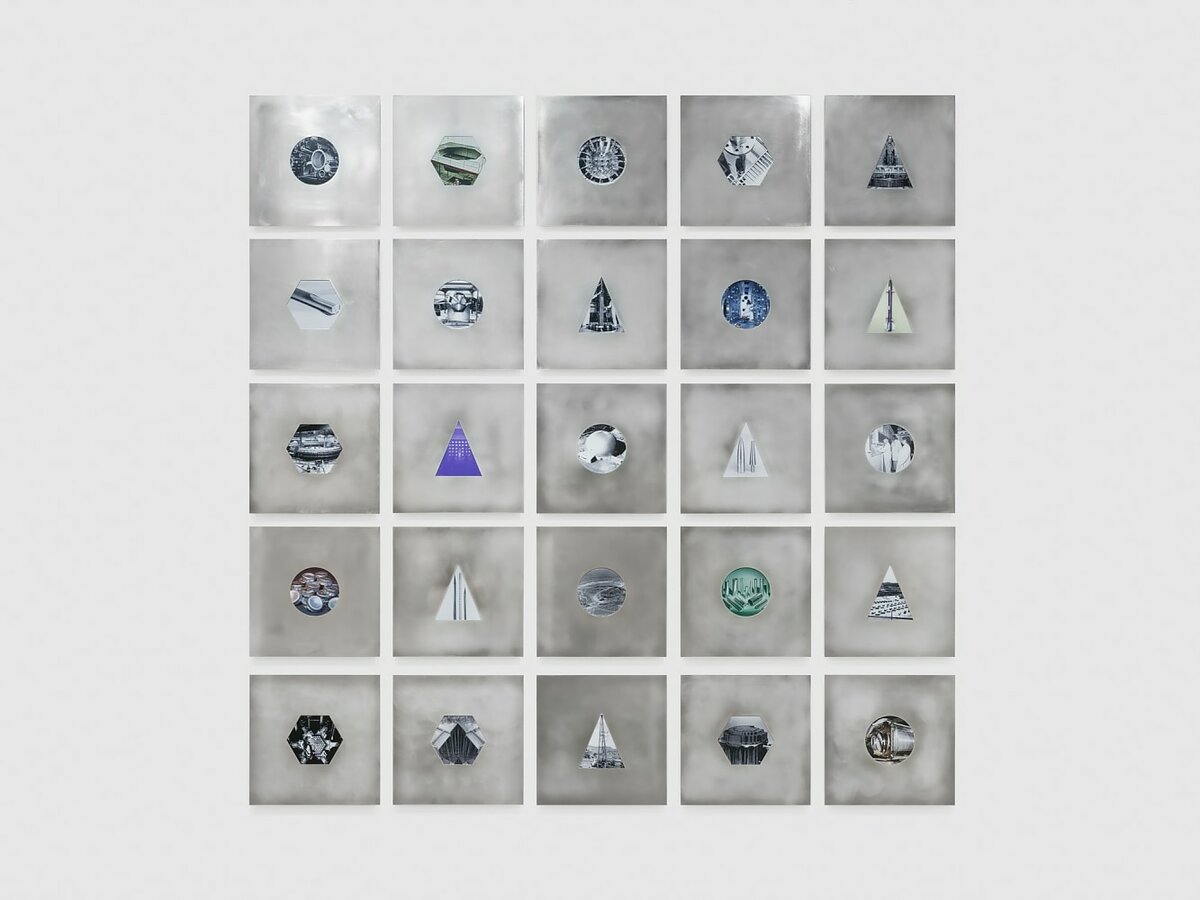

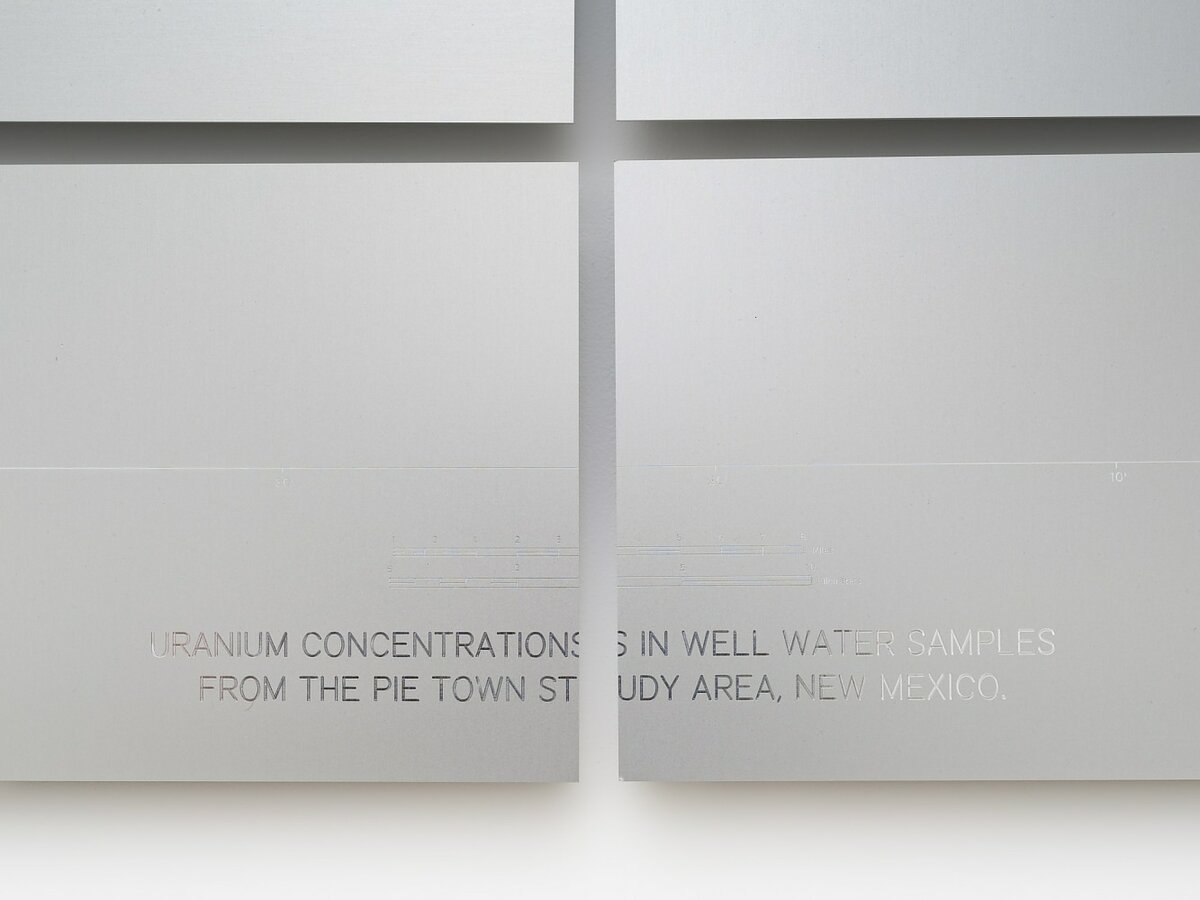

The space was populated with steel “containment structures” that echoed de Maria’s geometric forms. Each of them bore uranium in various states: as mineral fragments, infused into glass, in soil samples. “I’m not trying to make art about these really large scale systems, but art that engages with them, that is a part of them,” said Wang as we walked through the exhibition. For “Yellow Earth,” this meant bringing contamination into the gallery space through these irradiated samples, weaving unexpected threads between the sites of New Mexico and New York. This contamination collapses the distance between what might be considered “there” and “here,” generating a new topology of shared responsibility and history that connects ground zero of atomic experimentation and land art with America’s artistic and financial capital.

It is these broader, fractaling webs that constitute the proper subject of Wang’s works—an infrastructural sensibility that betrays his formal training as an architect. “I always want you to understand the artwork as plugged into something larger, and that’s where the work resides, in that relationship,” he explained. By engaging with Wang’s pieces, the viewer also enters into these relational networks, becoming a part of these systems that often seem so out of reach.

This “something larger,” however, is rarely presented directly, but through absences and deferrals. Wang’s decision to obscure uranium fragments for instance, not only protects viewers from radioactive seepage, but urges us to begin questioning what else remains unseen—all those mutating forces of capital and power out of view. In a 2022 exhibition at La Casa Encendida in Madrid, Wang’s Contagion Garden featured infected tulips with a virus that striated their pedals, using these visible markers to gesture towards the viral cosmos underneath. Similarly, in 10000 li, 100 billion kilowatt-hours (2021), Wang produced a snowy landscape using dam energy powered by glacial melt, transforming the snow into an inverse signature of the glacier’s disappearance.

This approach sets him apart from others that have explored similar subjects. Where many have reflected upon these vast phenomena through works that aspire to their scale, Wang approaches these subjects with an understated humility. The artifacts he makes are delicate and intimately rendered despite their world-spanning imbrications. Wang admits that tackling these subjects can easily become “megalomaniacal,” and uses oblique maneuvers like obfuscation, synecdoche, and transformation to reflect his awareness that it’s impossible to fully capture these entities. “It’s important that this art has a life and movement of its own,” he said. “That it isn’t something I can control.”

There’s a popular adage attributed to the American literary critic and philosopher Fredrich Jameson: that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. The phrase has become a depressive slogan of sorts, giving voice to the feeling that the forces shaping our lives are so colossal that it’s impossible to imagine what it might mean to grasp and change them. Discourse today remains stuck between what the scholar Donna Haraway has called “sublime despair” and a “comic faith in technofixes.” It would be easy for someone like Wang, who is constantly grappling with these systems, to give into these easy binaries— yet he never does.

If there’s a single piece emblematic of this sensibility, it’s Extinct in New York (2019). For this work, Wang installed a series of greenhouses on Governer’s Island that reintroduced once-native fauna— which have since gone extinct in the area— into the site. The tenor was elegiac; it was hard not to feel the shadows of all those once vibrant ecosystems looming. But if you looked closely, you could also make out the specter of something else: possibility. Not the possibility of utopic salvation, but of aftermaths, returns, and regrowths.

“I’m interested in the unknowability of the future,” Wang told me, “in the post-apocalyptic, not as a state where everything lies in ruins, but as a condition that lets us ask: What comes after? What will the next flourishing be?” With his artwork, Wang reminds us that there’s so much more to our world than what we can see— possibilities we haven’t yet dared to dream of.

“Yellow Earth” is on view at at Bienvenu Steinberg & C through August 31, 2024.

—Leo Kim is an essayist and critic living in New York City. He’s written for Artnews, The Baffler, Wired and others.