Tracing the Migratory Histories of the Sari at the New York Historical

Paisley patterns layered with shades of deep red ripple across the walls like a living archive at the New York Historical Society’s current show, “The New York Sari.” At its entrance, the exhibition’s text honors the sari as a “diaspora garment,” explaining how Indian textiles traveled along the Silk Road and Egyptian ports before Portuguese ships arrived on India’s western coast in 1498. From there, it invites visitors into a layered narrative spanning colonial trade, contemporary art, family archives, and activist movements.

The gallery is intimate yet spacious, anchored by a single object: Artist Shradha Kochhar’s hand-spun khadi sculpture, positioned near the back wall, is the only piece that extends onto the open floor. Music hums gently through the gallery, fluidly ranging from Arooj Aftab to Miles Davis, Anoushka Shankar, and Alice Coltrane—diasporic musicians whose work has been deeply influenced by and rooted in India.

“The musical choices were about how those artists interact with each other and share musical influences, production influences, and occupy particular historical movements,” shared exhibition co-curator Salonee Bhaman. “They are also easy to listen to when you’re in a gallery.”

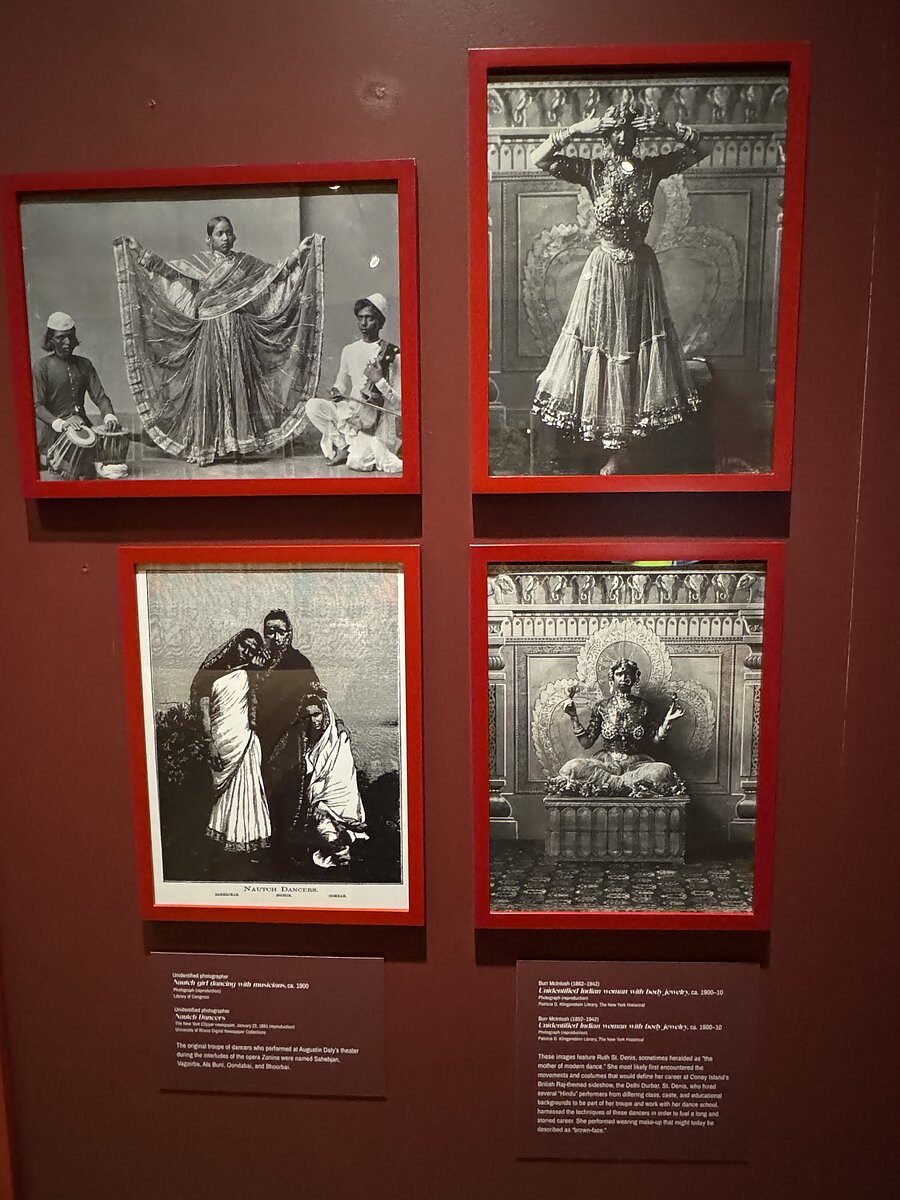

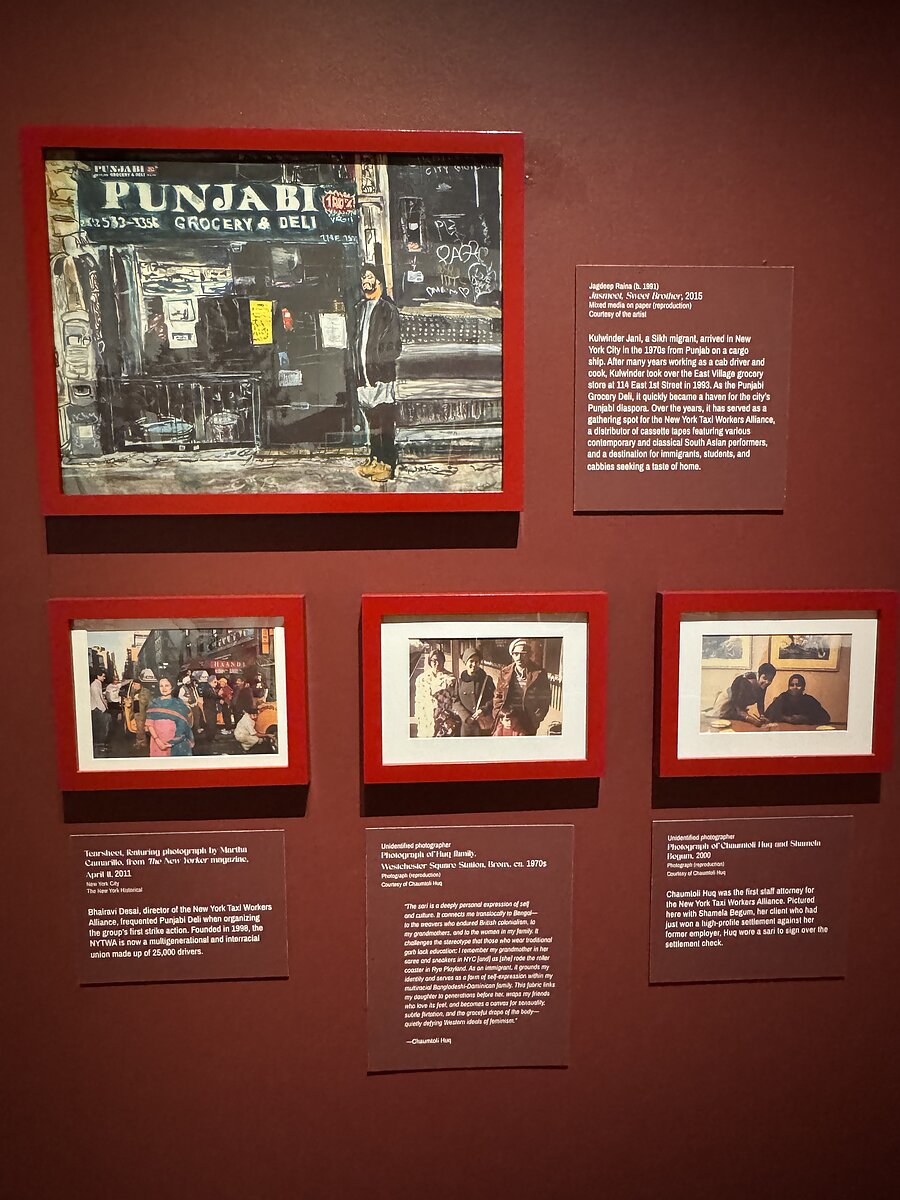

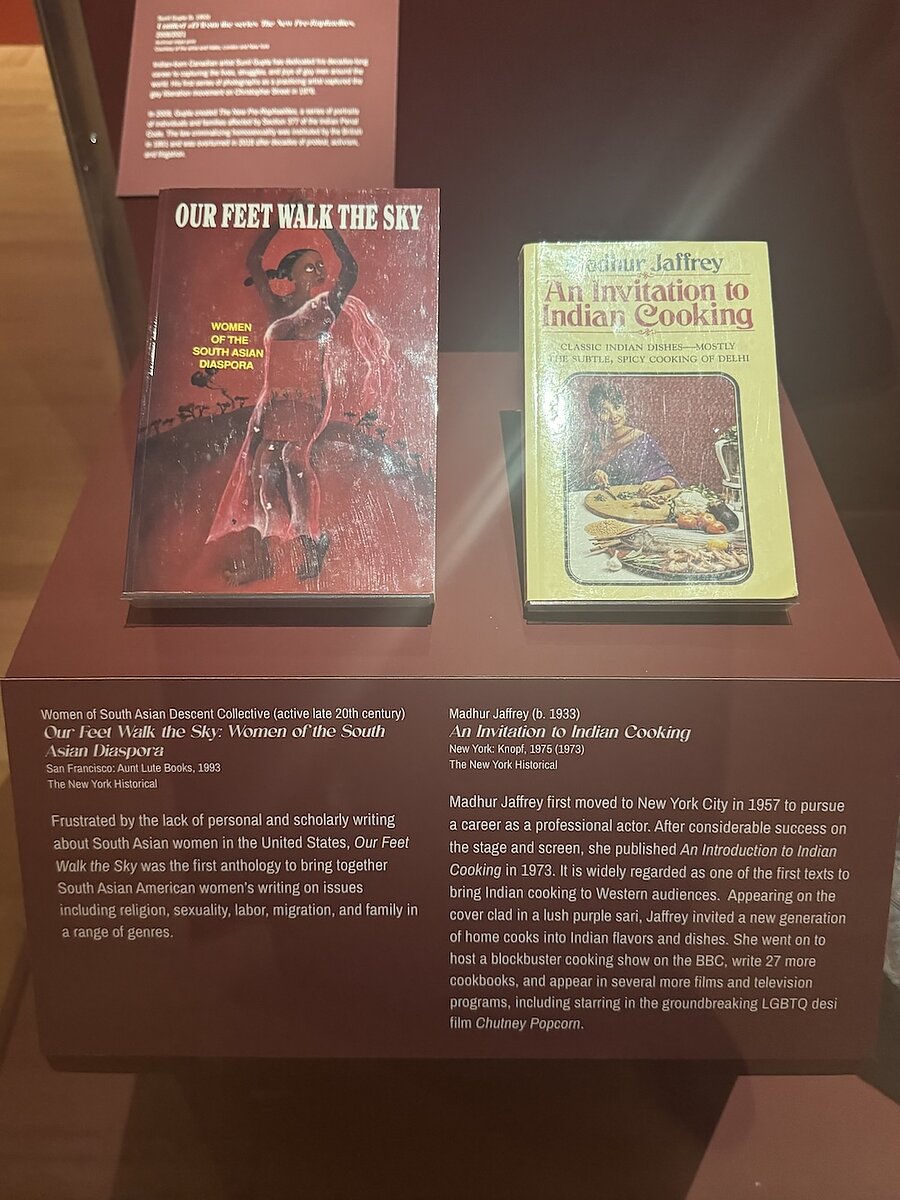

The exhibition’s interspersed archways and saturated fabric colors echo South Asian textile traditions and lattice architecture. When standing in the open space, a visitor can take one slow turn and see at least 70 percent of the entire exhibition which contains saris of different traditions draped on mannequins, as well as representations of saris in photographs, artworks, books, and various historical objects. These collections are organized into thematic sections—Consumer’s Empire, Empowerment & Craft, Migration & The Law, Dance & Performance, and Building Community—a format that thoughtfully resists linear storytelling.

On one wall are 27 prints from Chitra Ganesh’s “Sultana’s Dream,” a linocut series re-imagining Bengali feminist activist and writer Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s 1905 sci-fi feminist utopian text of the same name. The prints showcase women clad in saris, pants, helmets, and more, pointing to gender inequality as among the persisting problems of the 21st century.

Most of the actual saris on display come from influential South Asian New Yorkers who have worn them. The sari Sudha Acharya, executive director of the South Asian Council for Social Services, wore to her daughter’s wedding reception in South India is draped in one corner. Meanwhile a traditional Nepali sari was loaned by Narbada Chhetri, the former co-executive director of Adhikaar, a New York–based nonprofit serving the city’s Nepali-speaking community.

The heart of “The New York Sari” lies in its intimacy: the stories, objects, and fabrics that sit together reflect belonging and resistance. In the corner dedicated to explorations of the sari and gender, Bhaman included flyers from the South Asian Lesbian and Gay Association (SALGA), and a Trikone magazine featuring the late LGBTQIA+ activist Urvashi Vaid. “Historically, it has been a struggle for SALGA to be accepted as part of the community,” she said. “To include them felt healing. It felt like a family reunion.”

In the ‘Empowerment & Craft’ section, there is a copy of W.E.B Du Bois’s 1928 political and romantic novel Dark Princess, which explores depictions of the beauty of people of color around the world resisting imperialism. Included among these depictions is a story of the fictive ruler Princess Kautilya. The book is placed alongside two of its contemporaries, Agnes Smedley’s Daughter of Earth and Pauli Murray’s Song in a Weary Throat, the latter of whom was inspired by the philosophy of Satyagraha. These texts mirror the sari’s journey across continents and meanings, showing how a textile, like a story, carries histories of struggle, admiration, and exchange. They also trace how African American luminaries during the Harlem Renaissance looked to the East and the Indian freedom struggle as sources of inspiration for imagining new forms of beauty, liberation, and solidarity among people of color.

Working with Anna Danziger Halperin, Bhaman spent 18 months shaping an exhibition that identifies the sari as an essential thread in New York’s historical and cultural fabric. The idea for the exhibition first emerged in a conversation between Councilmember Shekar Krishnan, New-York Historical Society’s president Louise Mirrer, and Mitra Kalita of Epicenter Media about textiles, Jackson Heights, and how their mothers’ saris connected them to memory and migration.

In collaboration with art directors Kira Hwang and Claudia Lynn, Bhaman and Halperin wanted the space to evoke the metaphorical, physical, and historical movement of the sari. The paisley pattern, for example, is named after a town in Scotland—but elsewhere in the world, it is also referred to as mango, mango seed, or budding flower, placing it anywhere within and between India and Iran.

“If ever there was a little parable about how colonialism, textile manufacturing, art, design, and our own ideas of these things have melded, it is paisley” noted Bhaman, also explaining how it recalls the 1970s, a period when the East met the West in fashion and music.

In this spirit, “The New York Sari” refuses to flatten history. It moves like the garment itself: fluid, layered, and alive across time periods and generations. One leaves the exhibit feeling seen and stirred: “The number of South Asians who’ve said, ‘I learned something about myself,’” Bhaman exclaimed. “That was exciting for me!”

“The New York Sari is currently on view at the New York Historical Society through April 26, 2026.

—Nimarta Narang is a Thai Punjabi writer and journalist from Bangkok, Thailand, who is now based in New York. Narang was a part of Gold House’s 2023 Journalism Accelerator, 2023 Autumn Incubator, Tin House’s 2024 Winter Workshop, and 2024 Aspen Summer Words. In 2024, she was honored with the Young Alumni Achievement Award from Tufts University and the Asian American Journalists Association’s Suzanne Ahn Civic Engagement & Social Justice Award.