The Enduring Influence of Rupi Kaur on AAPI Poetry

About 10 minutes into Rupi Kaur’s hour-long Amazon special, “Rupi Kaur Live,” the poet shares that she was born in Punjab, India and moved to Toronto’s Brampton when she was three and a half. She didn’t learn English until the third grade.

“Even though I grew up in Canada, when I got home after school, you better believe I was walking right back into the motherland,” she says. “We had to speak, read, write, live, breathe, everything Punjabi.”

Kaur goes on to describe how kids at school would make fun of her accented English, and her cousins in Punjab would make fun of her accented Punjabi. “And that’s when I realized, I’m fucked! These kids don’t give a shit about me! So I’m just going to sit here and keep shape-shifting between these two worlds because I am pretty damn good at it.”

I happened to be in the audience at the Los Angeles event featured in the special. Being a Punjabi woman myself, the show was the first time I had witnessed someone with the surname “Kaur” take center stage in such a mainstream way in the west. A gold hair band glistened like a crown on Kaur’s head whilst her white gown shimmered on stage. A projection of flowery illustrations circled her in ever-changing colors, bringing her images to life. Even the white girls around me were crying when Kaur recounted immigrant experiences I was intimate with. It was a sold-out show for a celebrity poet and artist whose love for performing was entrancing to watch.

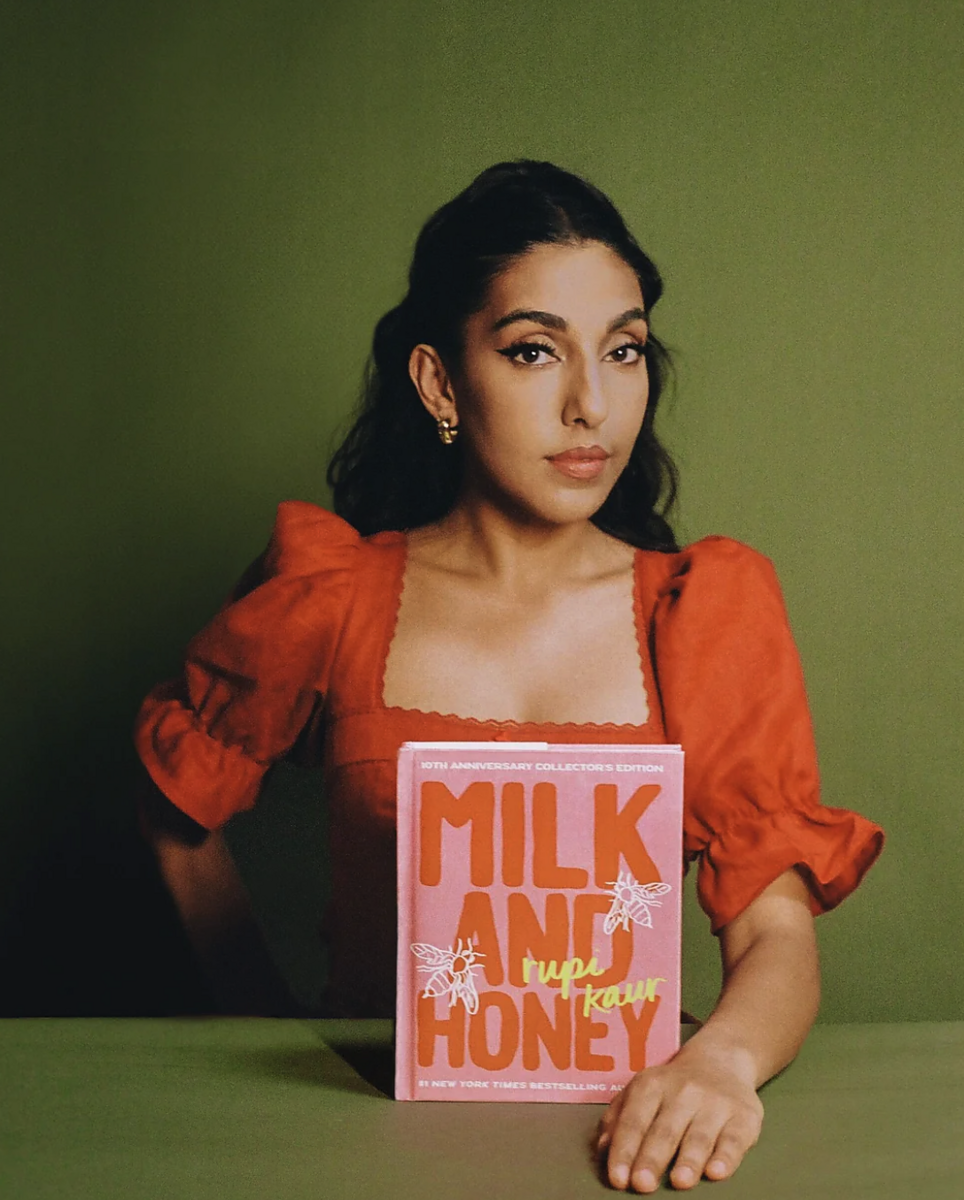

This November marked the 10-year-anniversary of Kaur’s self-published debut poetry collection Milk and Honey that first catapulted her into literary stardom. While recipients of her work range from avid fans to unimpressed critics, the book of poetry and illustrations has sold over 6 million copies and is touted as one of the highest-selling poetry books of the 21st century, cementing the indisputability of Kaur’s impact.

Influenced by Gurmukhi, a Punjabi scripture, the written form of Kaur’s poetry has become extremely recognizable; there are no upper and lower cases as all letters are treated the same–reflecting the tenet of equality in Sikhism–and there is only one punctuation of a period.

“It is less about breaking the rules of English (although that’s pretty fun) but more about tying in my own history and heritage within my work,” writes Kaur on her website.

Celebrating a decade since its publication, Kaur created a collector’s edition of Milk and Honey. Released on October 1, it includes her hand-written annotations of the poems over the years, a new chapter titled “The Remembering” with unpublished poetry that didn’t make it into the first manuscript, new illustrations, and archival diary entries. It also includes a new cover and introduction. “It’s like a Director’s cut of a movie,” said Marie Claire editor-in-chief Nikki Ogunnaike in a recent podcast interview with Kaur.

The additions are meant to account for how Kaur has perceived her own growth over the years, including a 2015 incident in which Meta took down a now viral self-portrait of Kaur from a university project that tackled the stigmas around menstruation. The action prompted Kaur to call out the social media platform, writing, “Their patriarchy is leaking. Their misogyny is leaking.”

For Pooja Shah, Kaur’s actions were a refreshing act of bravery. “The pure, unfiltered honesty of sharing her experiences no matter how emotional, traumatic, or raw they are [resonated with me],” said Shah. “It takes a lot to put your own life on display through your words and that really inspires me.”

Shah is a corporate lawyer and freelance writer from New York who is now living in London. She vehemently states that she would “die on the Rupi hill.” She turned to Kaur’s poetry in 2014 when going through a law school relationship, and saw many parallels between their experiences.

“I felt like as a South Asian woman, she was discussing topics that so many in our diaspora can relate to. It almost felt like she was our very own therapist or big sister who had gone through universal experiences and was imparting her wisdom.”

With 4.5 million followers on Instagram, Kaur has become the poster child for the growing phenomenon and popularity of poetry on social media. This trend—and, as a result, Kaur—has been controversial. On the one hand, it has been argued that Instagram has “saved poetry” at a time when public interest in the genre has been otherwise absent. On the other, critics have cautioned that the world of Instagram poets is more about branding than it is artistry. Still, the fact remains—Kaur’s methods have proven that, when made accessible, there is an enormous appetite for poetry.

Kaur partly attributes this tendency toward accessibility to her culture. In an interview with Cold Tea Collective, Kaur shared, “Poetry in Punjab and most of the East is accessible. My grandparents couldn’t read or write. They had poetry because it was an oral tradition and it was accessible to all, no matter what class you were.”

Pavana Reddy, a South Indian and Fijian poet and songwriter based in Los Angeles, shares her poetry online as well. She started sharing her work on Tumblr 10 years ago and then transitioned to Instagram in an effort to reach more audiences. Known for her poetry collections, Rangoli and Where Do You Go Alone, while Reddy enjoys engaging with her readers online, she has found social media to be more cumbersome over the years. “I’ve noticed that a lot of what I want to share on social media doesn’t get the interactions I’d expect it to, considering it’s still a poem,” said Reddy. “What does get attention are sentiments that have been recycled over and over and I’m not sure why that is.”

“I think social media has watered down poetry. What used to be original well known works are now being rewritten and kind of shrunken to fit an aesthetic,” she continued, lamenting the way in which many poets today seem to be trying to recreate milk and honey. “It’s stunting a lot of growth in the poetry world.

While clearly popular, Kaur’s reception is not universally positive. Critics of her work have accused her of trying to essentialize the South Asian female experience and use personal and collective trauma as a brand strategy. She has also been accused of plagiarism.

In releasing this new edition, Kaur is perhaps taking the opportunity to reflect and respond to these criticisms, along with her role as a celebrity “Instapoet.” But unlike viral trends, her style and form are not a passing fad. In December 2019, The New Republic deemed Kaur “writer of the decade” – a decision that received backlash. However controversial her work may be, Kaur’s work has left an impression in the literary world that will be studied and analyzed in the way more traditional poetry have been–and maybe that is a marker of success in itself. In the next few months, Kaur is embarking on a tour across the US to connect with readers at local bookstores, which is, in my experience, the best way to experience Kaur’s work–through her readings.

—Nimarta Narang is a Thai Punjabi writer and journalist from Bangkok, Thailand, who is now based in New York. Narang was a part of Gold House’s 2023 Journalism Accelerator, 2023 Autumn Incubator, Tin House’s 2024 Winter Workshop, and 2024 Aspen Summer Words. In 2024, she was honored with the Young Alumni Achievement Award from Tufts University and the Asian American Journalists Association’s Suzanne Ahn Civic Engagement & Social Justice Award.