How Asian Americans Found a Home in Hip-Hop

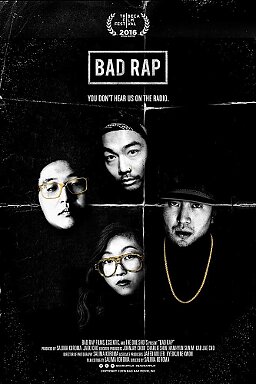

When hip-hop turned 50 on Aug. 11, 2023, prominent Korean American rapper Dumbfoundead, along with his friends and fellow subjects of the 2016 Bad Rap documentary, Rekstizzy and Lyricks, shared a special episode of the podcast Fun With Dumb to close out the month’s celebrations. The three Korean American rappers reflected on 50 years of hip-hop, discussing their respective journeys.

Lyricks spoke about getting scolded by his parents when he played Coolio’s Gangsta’s Paradise album in the car. Rekstizzy shared that he once cried after listening to Common’s “Retrospect for Life" because of how real the lyrics about abortion were. He also shared that listening to dead prez was how he learned about systemic racism.

“We wouldn’t have learned about it if it wasn’t for hip-hop,” Dumbfoundead added. “If anything, hip-hop gives us a voice to share our stories the way it did for the Black community. Not a lot of people would listen to that story unless it was presented through rap.”

To honor AAPI contributions to hip-hop is to understand that our community isn’t a monolith—the genre has produced rappers from many different ethnic backgrounds, who come from cities near hip-hop hubs across America, and are byproducts of the rap eras they came up in. Many Asian American rappers have been accepted for their rap purist’s perspective, being mindful of the genre born from Black and brown youth in the South Bronx in the late ‘70s.

It would be careless to document a history of Asian Americans in hip-hop without mentioning figures like Chad Hugo of The Neptunes, Dan “The Automator” Nakamura, DJ Qbert and Invisibl Skratch Piklz, Geologic of Blue Scholars, Far East Movement, apl.de.ap of Black Eyed Peas, Awkwafina, Lyrics Born, Guapdad 4000, Jay Park, Raja Kumari, Year of the Ox, Flowsik, Stupid Young, MBNel, China Mac, Cool Calm Pete, P-Lo, Chow Mane, Spence Lee, Bohan Phoenix, Anik Khan, Ted Park, Kid Trunks, Snacky Chan, Bambu, Ruby Ibarra, Rocky Rivera, G Yamazawa, and the entire Beatrock Music roster. Still, it’s only been in the past few years that artists like Anderson. Paak, Bruno Mars, and H.E.R. have become household names foregrounding their AAPI heritage.

While a definitive history of Asian Americans in hip-hop is fragmented, Chinese-American rapper, activist, and educator Jason Chu believes that one can trace its contours via the circumstances of immigration to the US and the resulting exchange that happens when cultures meet.

“I think what a lot of people don’t understand is that we are embedded in and proximal to [Black and brown] communities,” said Chu. “Vietnamese communities, Laotian, Khmer, South Asians—When we came to this country, especially the refugee population, it was not like Viet folks or Hmong folks were resettled into bougie suburban white areas. They were resettled right into the hood.”

Chu argues that the product of this proximity is a culture that is rooted in solidarity. “I think we got to have this liberating, grounded, real understanding of what America is and what American communities are,” he said. “These strict racial boundaries and boundaries of cultural origin that work well in theory completely fall apart when you look at how and where people live and interact.”

Some of the first Asian American artists to gain recognition in hip-hop in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s are a testament to Chu’s theory. On the East Coast, the late Fresh Kid Ice, Mountain Brothers, and MC Jin all reflected the cross-cultural solidarity that hip-hop presented.

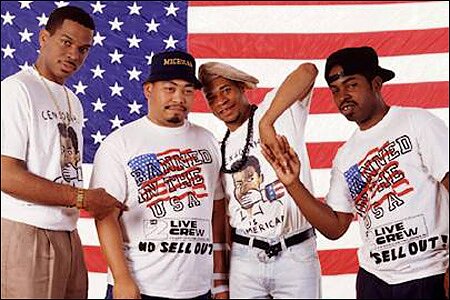

Born Christopher Wong Won, Miami-based Trinidadian American rapper Fresh Kid Ice is often cited as the first Asian American rapper, co-founding the Miami bass group 2 Live Crew. He was part of the 1989 album As Nasty as They Wanna Be, which broke ground on many levels—it was ruled obscene by a federal judge on June 6, 1990. Despite this ruling, and even after record stores were advised to boycott the album, it went on to sell over two million copies.

On Fresh Kid Ice’s 1992 solo album The Chinaman, the rapper continued 2 Live Crew’s explicit nature, releasing singles like “Dick ‘Em Down”—an original “Mr. Steal Your Girl” anthem. Other songs declare that size matters for Asian American men, rapping in “Long Dick Chinese” that he’s a “bad motherfucker.”

In 1996, despite experiencing racism while courting labels (a rep reportedly told them to dress up on stage in karate gis and rap battle with gongs behind them) Philadelphia’s Mountain Brothers became the first Asian American hip-hop group to secure a major label deal with Ruffhouse/Columbia Records, whose roster included The Fugees, Cypress Hill, Kris Kross, Wyclef Jean, and Lauryn Hill.

The members of Mountain Brothers were Scott Jung (Chops), Christopher Wang (Peril-L), and Steve Wei (Styles Infinite), a trio of Chinese American rappers who, on songs like “Paperchase,” off their 1999 record, Self: Volume 1, showcase their lyrical mastery: “Lemme state my case about the paperchase / I know it’s hard tryin’ to escape the pace / Of the fast lane situated in a gold-plated Camry, Lex, or Benz / But what about support-related family checks for friends?”

“The first time I ever heard of these dudes was because I had that iconic experience of walking in and flipping through albums, seeing cover art, and seeing the name already,” Chu said. He is currently collaborating with Mountain Brothers’s Chops. “I was into kung-fu and anime, the album cover almost had anime illustrations of all three of them. I was like, ‘Yo, this feels something familiar.’”

Then there’s New York City’s own Freestyle Friday champ, MC Jin. With his razor wit, Eminem-like flow, and confident delivery, MC Jin (Jin Au-Yeung), is likely one of the best-known Asian American rappers of his generation. Considered both a novelty and a trailblazer, the Queens-based artist first made history in 2002 by winning 106 & Park’s Freestyle Friday seven weeks in a row. Part of what set him apart was his deft ability to switch flows between Cantonese and English. From there, he became the first Asian American solo artist signed to Ruff Ryders Records, home to DMX and Eve, and worked with producers such as Kanye West, Swizz Beatz, Just Blaze, and Wyclef Jean.

While Jin’s 2004 debut single “Learn Chinese” was heavily criticized for ghettoizing New York Chinatown and tokenizing his ethnicity, demanding that his listeners learn Chinese in the early 2000s when Asian Americans and immigrants more broadly were constantly being told to learn English was also empowering: “I ain’t ya 50 Cent, I ain’t ya Eminem, I ain’t ya Jigga Man, I’m a Chinaman.”

Also hailing from Queens is Himanshu Kumar Suri, better known as Heems. For many South Asians growing up on the East Coast, Heems, a Punjabi-Indian American MC, was one of the first rappers that represented their experience. Heems remembers gravitating towards rap from a young age, spotting stickers of Nas from his street team at the basketball courts in the park.

“Rap historically has been a language and a medium of artwork for the disadvantaged and those who don’t have a voice in other parts of society,” said Heems.“It was the closest thing I saw to me that made sense in terms of voicing the experience of an outsider or someone that hasn’t been granted the same resources as someone else in society.”

Heems made his name as part of Das Racist and Swet Shop Boys. Along with fellow MC Kool A.D. (Victor Vazquez) and hype man Ashok Kondabolu, Das Racist gained mainstream notoriety in 2010 when their absurd, borderline parody track, “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell,” became an early example of internet virality.

His debut studio album as a solo artist in 2015, Eat Pray Thug, was recorded mostly in India and focused on life in a post-9/11 America, using songs like “So NY” and “Flag Shopping” to talk about race and identity: “I know why they mad / But why call us A-rabs We sad like they sad / But now we buy they flags.”

His upcoming album Veena, named after his mom, will be an amalgamation of his past projects, mixing in his distinctive brand of humor and social commentary to explore trauma, addiction, spirituality, healing, and growing older. He recently signed a new deal with Nas’s label Mass Appeal, partnering with his imprint Veena Sounds to release music.

While Heems doesn’t believe there has been enough South Asian representation in hip-hop historically, he sees the landscape rapidly changing. “I think now seeing themselves represented in pop culture, there are a lot more South Asians making music,” he reflected. “I think there are also a lot of South Asians now who have the resources, they didn’t grow up with working-class parents. They can take risks, which we didn’t really have the opportunity or ability to do.”

“If there’s one connecting point, perhaps it’s the notion of outsider-ship,” he continued. “Whether that’s being from Queens and looking into Manhattan or whether it’s being Indian and looking at America. You don’t have to belong to the larger conversation; you can build your own conversation.” This is a fitting statement coming from Heems who has become a cornerstone of the indie rap scene, teasing collaborations with Open Mike Eagle, Quelle Chris, Kool Keith, Mr. Cheeks from the Lost Boyz, and Cool Calm Pete.

In the 50 years since its distinctive sounds were first broadcast at a South Bronx block party, hip-hop has evolved tremendously. Today, women rappers are at the top of the charts, and the culture has become a global force. The most talked-about collaborations tend to be international: Latto became the first rapper to score No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2023 with “Seven” featuring BTS’s Jung Kook. J. Cole continued his guest verse run by appearing on BTS’s J. Hope’s “On the Street.” Eminem signed Filipino rapper Ez Mil after discovering him with Dr. Dre and hopped on the remix to “Realest.”

In the United States, countless AAPI artists have broken into the hip-hop mainstream, proudly representing their identities. In addition to the aforementioned Dumbfoundead, Rekstizzy and Lyricks, artists like Jhené Aiko, H.E.R., Audrey Nuna, Tyga, Saweetie, Yaeji, TiaCorine, Amerie, and Kelis only scratch the surface of representation. The Sean Miyashiro-led 88Rising label and Head in the Clouds Festival have also been incredibly influential forces in developing and promoting AAPI and Asian diasporic hip-hop.

It feels as though Asian Americans have finally reached a point of belonging in hip-hop, where we can voice and represent our identities on our terms. “Hip-hop was my first ethnic studies class,” Chu said. “If I can see what Fred Hampton, Angela Davis, Sojourner Truth, or Harriet Tubman mean to a Black woman or man spitting their truth, I want to identify the Asian American figures that give me the same strength. Can I do that with Yuri Kochiyama, Larry Itliong, or Mabel Ping-Hua Lee? Any of our cultural figures? Can I make them a symbol of pride and aspirational leadership the same way Spike Lee made Malcolm X?”

The answer is yes. In Chu’s own words in “Imposter Syndrome” off of his latest release, We Were the Seeds: “A pilgrimage to Yuri Kochiyama grave / We belong here, fuck your toleration / Ancestors laid the tracks that unified this nation / Libations and baijiu orations / And it never came easy, but the goal was worth the waiting.”