At “Dwelling,” Home is in the Subconscious

Sheltering from the beating sun outside on a recent weekday afternoon, I turned over the following thought while viewing “Dwelling,” a show of interior paintings at Canal Projects: If a murderer with an ax lunges at me while I’m conscious, he is at fault. But if a murderer with an ax appears before me in my dream, I am at fault—I have conjured him from the depths of my subconscious. Who knows why? In dreams and in art, we can more readily dissolve the borders between ourselves and the world and render ourselves porous.

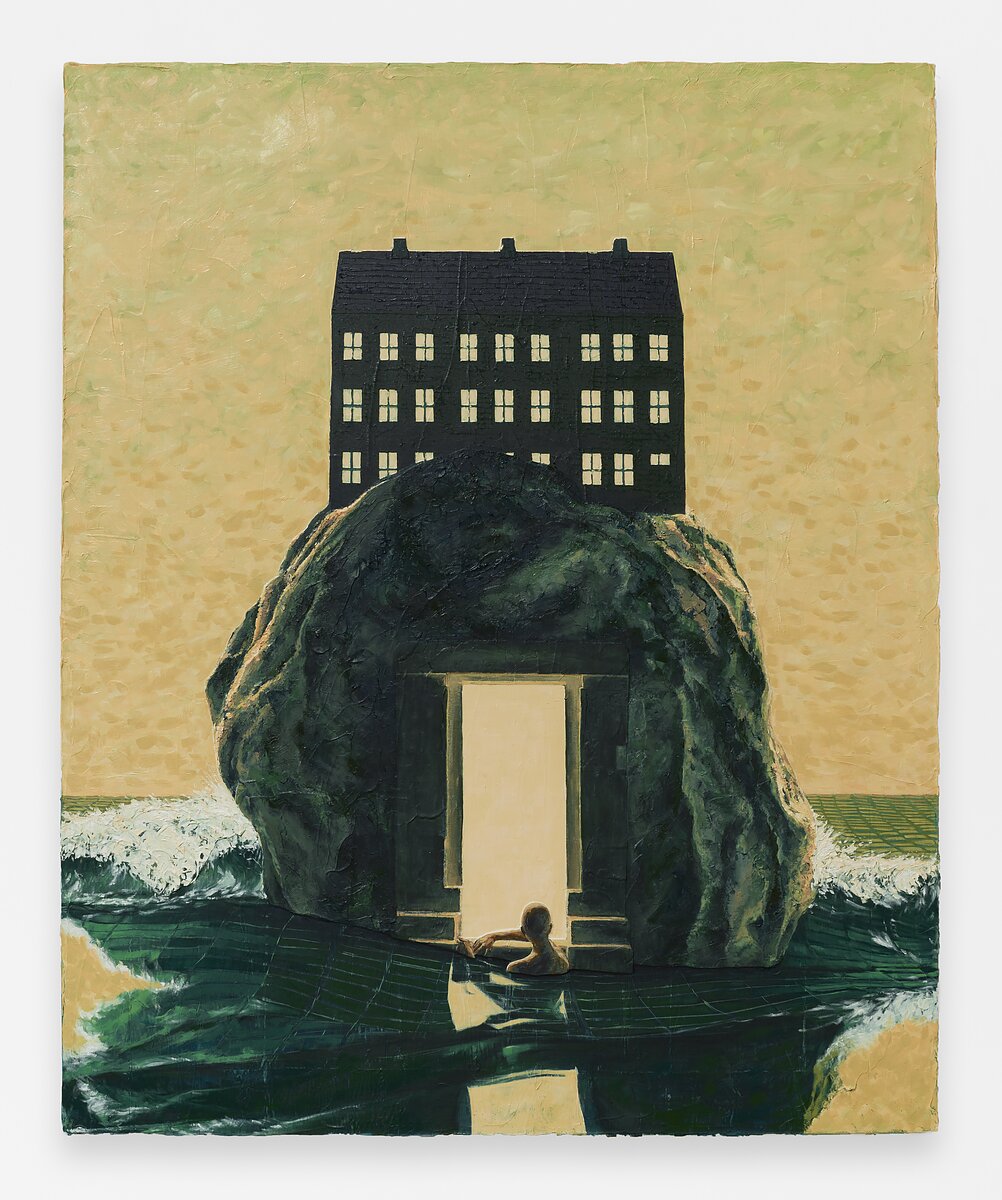

This thought came to me as I considered Ho Jae Kim’s House with an Ocean View (2023). It depicts a surreal scene. Surrounded on all sides by the ocean, a solid stone portal is encased by a boulder and topped by a black cutout of a house. The surface of the water carries a tiled pattern and crashes around the rock in frothy waves. A bald man, submerged beneath his chest in water, rests on the threshold of the gateway in a meditative pose, looking out into the blinding gold light before him.

The eponymous house with a view, a three-storied building perched above the boulder, appears nondescript, unreal, and unhouselike with its many uniform windows and its deliberate lack of detailing. The house, flat and storybook-like, is inaccessible and invisible to the man below. His place by the doorstep is a temporary one that allows him to see something of the beyond. The architecture of this scene makes the imagination of the man amidst it manifest, a man both constrained and yearning.

Kim has an interest in in-between spaces. Earlier this year, I saw a suite of his paintings at his solo show, “Carousel,” at Harper’s Gallery. Tiles and arches, suffused in gold light; palm trees; man-made isles; heads sliced horizontally at eye level—these are the motifs that recur in Kim’s paintings. Some of his ethereal human subjects, as well as his climates and architectures, seem distinctly Asian or Asian-inspired. As in dreams, however, the provenance of Kim’s symbols remains uncertain. In place of firm references to definite places and identities, Kim is allusive, a style that perhaps has something to do with his vision of purgatorial spaces as “divine scenes of nothingness,” waiting rooms for lost souls suspended between the mundane and divine.

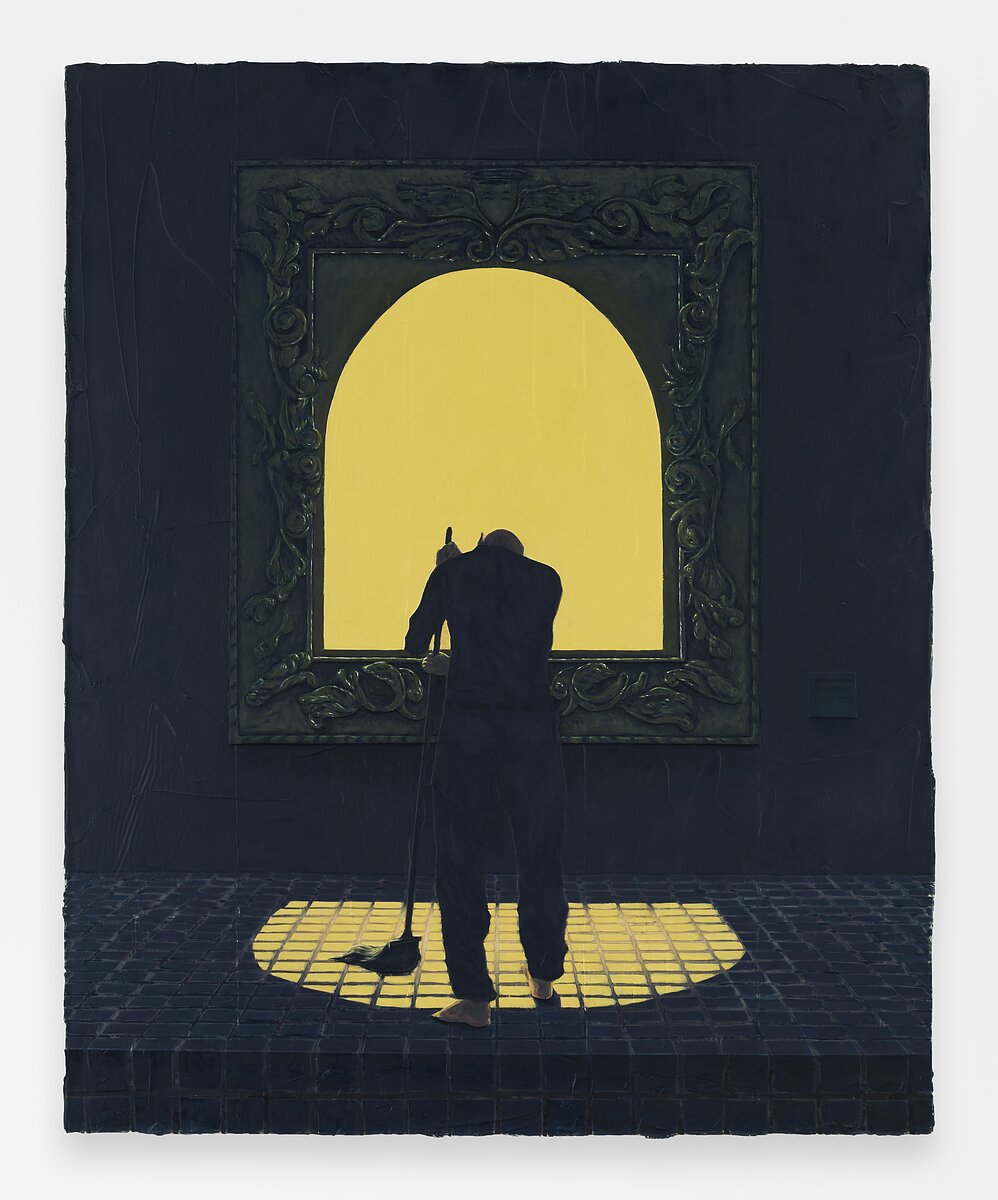

That Kim’s investment lies in providing some measure of salvation for his subjects is most evident in Day 3: Janitor (2022). In this liminal space, there is no searching examination of the psychology of the cold, dark, tiled room’s proprietor. To the extent that the janitor’s surroundings are a character, it is its characterlessness that deepens the injustice of his toil. The austerity of the space foregrounds the divinity of the golden light, which overflows from a painting within the painting and pools at his feet.

Even the baroque frame of the piece is burdensome and mundane, a profane object requiring upkeep and human exertion; only the monochromatic light heralds the possibility of life beyond labor. In contrast to House with an Ocean View, Day 3: Janitor is strict in compartmentalizing the mystical. Surrealism gives way to pure religiosity. Wiped of the perambulant oddities of a mind drifting away from logic and reason, there is a cold insistence to the painting, borne out of harsh realities.

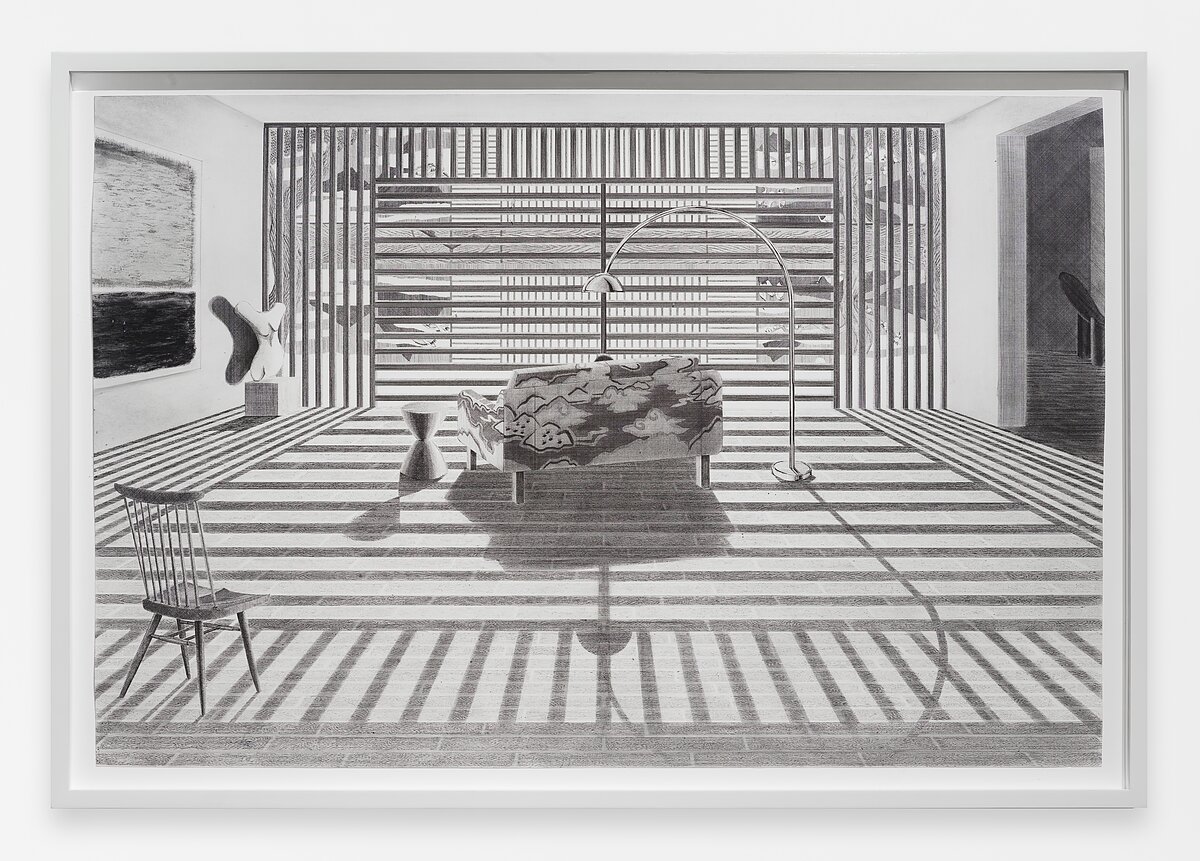

Sigmund Freud, believing it possible to achieve greater dominance over the territory within, suggested that the composition of a room could induce the realization of new truths, an insight foundational to the practice of psychoanalysis. For a session to achieve its optimal effects, the patient was to lie recumbent on the couch, facing away from the analyst. This arrangement is the subject of Kyung Me’s Papillon de Nuit I (2019), which shows the backside of a couch upholstered with a cloud-patterned textile. Facing the couch from a distance is a chair. A spectacularly arched floor lamp is trained, ostensibly, on the patient.

The visual excitement produced by Me’s intense attention to surfaces—the grooves in the wooden chair, the uneven layers of paint on a Rothko painting hanging on the wall, the marbled curves of a limbless sculpture—is heightened by their uniform representation with ink, charcoal, and graphite. The medium is a scrupulous one that connotes knowledge and control. Mysteries of interiority are subjugated to the clinical setting.

If the physical landscapes that appear before us when we are asleep are projections of latent states of mind, it’s implied that the inverse holds, too. The layouts we scrupulously design when we are awake contain powerful expressions of unconscious desires. The writer Janet Malcolm, who dedicated significant journalistic attention to psychoanalysis, was a proponent of this idea and scrutinized the interiors of homes closely to understand her subjects, seeing in them the furniture of their psyches.

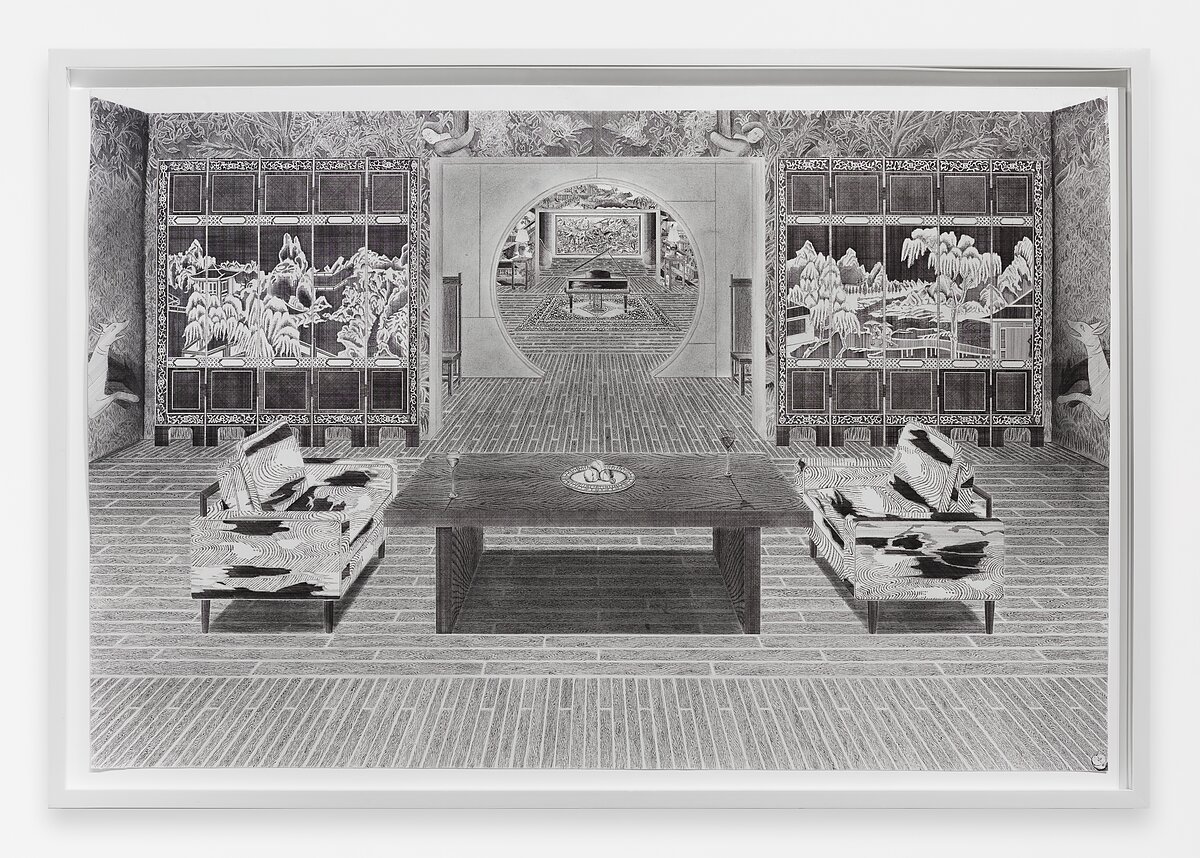

The drawing of Me’s included in “Dwelling” that I like most is Papillon de Nuit VI (2019), which portrays a room that opens into a room, opening into another room. There is a somnambulant claustrophobia to the architecture of endlessly unfolding spaces. Its ambitions are to accomplish an internalization of the external world, to exercise control over a boundless dominion—bids at a self-mastery so thoroughgoing it can only be guaranteed through the total mastery of one’s environs.

In this drawing, a living room occupies the foreground. Two wine glasses rest diagonally across from one another on the modern wooden coffee table. The table—too long for warm intimacy, too self-serious for leisure—is flanked by armchairs fashioned out of animal hide, suggesting a violence fastidiously kept out of sight. The precision of their placement implies a desire for psychological penetration. Here, the wine, which in most other settings would signal recreation, conspires to manipulate. The space, we suspect, has been staged for an imminent dramatic encounter.

Scenes of lush foliage carpet the walls. A ten-panel lacquered screen, laid flat against the wall, is adorned with typical Chinese scenes of harmony between man and nature: the roof of a pagoda nestled amongst trees, two figures hiking up a path under their parasols. In the recessed rooms, there are more scenes of traditional Asian architecture alongside trees, a painting of a chaotic clash of birds. This elaborate interior, with its traditional quotations, bears the ego of somebody who believes they have triumphantly arrived at the end of history. With curiosity, it displays vestiges of man’s vanquished struggle to find the right relationship with his surroundings. The lodestar of this interior, however, is complete and utter reclusion from the world.

This space represents both an outpouring of neuroses and an attempt to dominate them. I’m reminded of J.K. Huysman’s À Rebours (translated alternately as Against the Grain or Against Nature). The protagonist of that book, the languorous neurotic Jean des Esseintes, sets out to furnish his home in rural Fontenay so completely that he may never need to step foot outside it again. He disdains nature, despises humanity, seeks to “substitute the vision of a reality for reality itself.” In a famous passage from the novel, des Esseintes, disappointed that his new pet tortoise is a drab presence on his oriental carpet, bejewels its shell so excessively that the animal promptly dies under its weight. Life in its organic state does not move des Esseintes, who wants to make it all new. This interior carries similar pretensions, embracing unfettered artifice, an image of a new domestic Asian modernity.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Kenrick McFarlane’s Untitled (Blue Soldiers) (2021) is a fluid interior less saddled by a sense of confinement. The molten texture of the painting emulates the evanescence of the social scene. For most other pieces in “Dwelling,” a detailed focus on interiors seems to be associated with solitude. Here, instead, the interior—with its liquefying walls, floors, and right angles—is part of the convivial mood, communicating more about the relations between its five occupants than their bodies and faces. McFarlane achieves this atmosphere with a breakdown of lines; the intrusion of pastel blobs and crimson lines; and two stout, expressionistically blue figures bedecked in tophats in the foreground. A woman on the left, talking to a dim figure, fashions something blue in her hands; a butler attends to business on the far right. Behind the woman is either a painting of a few sparse trees in a desert environment or a window. The intersubjectivity of the characters is given priority over their identities, and the sense is that the walls, objects, and colors in the painting speak, too.

Are the places we visit in our dreams internal or external to us? Surely they are part of us, or they wouldn’t appear in our dreams. Yet the rooms, towns, and landscapes we travel through in our sleep are regularly the strangest we ever inhabit, populated with unfamiliar signs in unfamiliar combinations. The paradox of our dreams is that they are both intimate and alien, confusing what lies inside and out, indicting us by our physical surroundings. Artistic portrayals of interior spaces, too, disintegrate these lines and show us that how we draw boundaries strikes at the heart of representation.

Jasmine Liu is a writer from the San Francisco Bay Area currently based in New York.