Artist Chella Man Explores the Cyborgian Experience of Being Trans and Deaf

Last summer, Chella Man found himself roaming the Venetian canals without sound. After forgetting his cochlear implant on a train, he crossed the bridges and braved the crowds of La Serenissima in innate silence. After going a full ten days without his hearing aid, the 24-year old artist, model, actor, and activist realized the possibility of a life without the device. “I found a liberating silver lining,” said Man, explaining how for most of his life, so much of his energy was spent on being able to understand and hear what people were saying.

After a lifetime of wearing machinery in order to assimilate to the hearing world, for the first time, Man was able to let go of having to bear the responsibility of communication. “I could put some burden on hearing people rather than just myself,” he said.

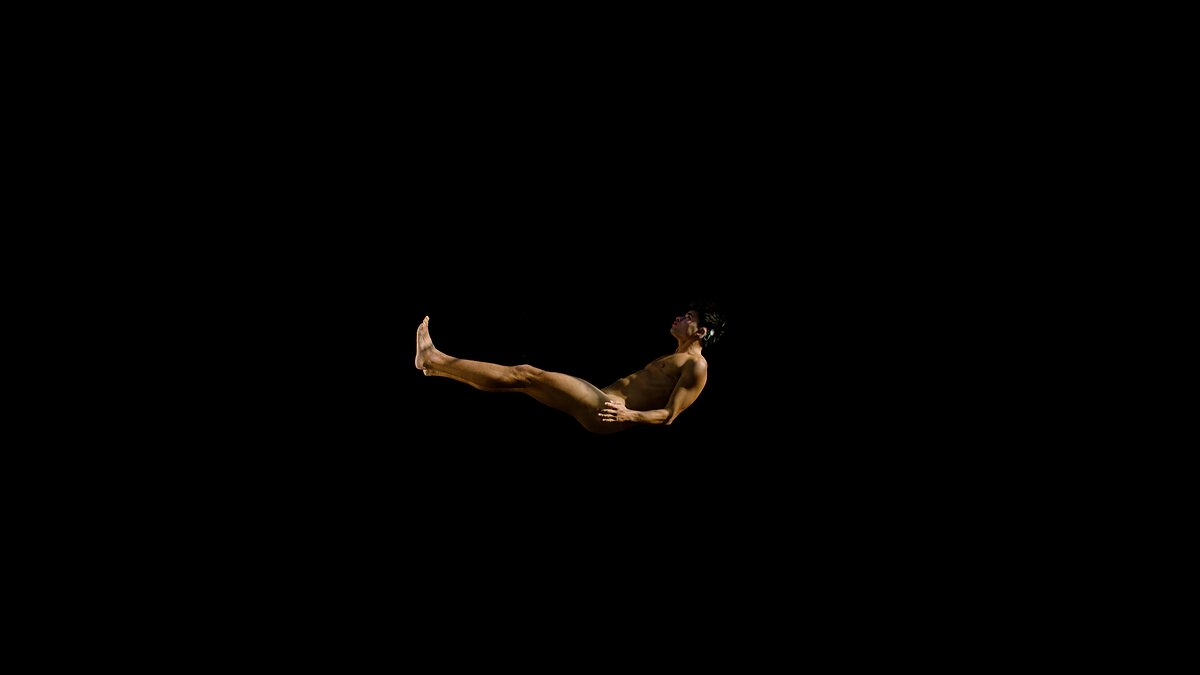

The fruit of this fresh chapter in Man’s life is a new short film titled The Device That Turned Me Into A Cyborg Was Born The Same Year As I Was, produced in collaboration with Australia’s Powerhouse Museum in Australia, Nowness, and New York’s Leslie Lohman Museum. Just over three minutes long, the film oscillates between Man’s dreams, memories, and contemplations about growing up deaf, trans, Chinese, and Jewish in a singular body in small town Pennsylvania.

The invitation to make a film about his complex relationship with his hearing device came from Powerhouse and Nowness serendipitously, before the organizations were aware of his inner reflections. “It was a sign from the universe,” said Man. He began storyboarding immediately. Having modeled for brands such as Calvin Klein, GAP, and Yves Saint Laurent and, most recently, acted in the online series Titans, Man was very familiar with being in front of the camera; being behind it, however, was uncharted territory. “It was extremely liberating,” he reflected. “I’ve been pigeonholed in the industry based on how the dominant society sees trans, biracial, and deaf individuals, so reclaiming the narrative and showing all my identities in my own way is so refreshing.”

The film’s fast pace feels similar to a video game or a memory, with quick jumps between his practical struggles living with a hearing device, childhood remembrances, and metaphorical dreams. “I experience life pretty fast, and the film is a window into my brain,” he said. “When I paint, I can’t use oil because it takes too long to dry!” While this rapid flow of imagery feels distinctly Gen Z, Man has felt this experience somewhat differently. “Deaf individuals have to put extra effort to keep our eyes on the screen to understand the world,” he explained. “If we look away for a second, we may miss out on the signs.” Similarly, the film challenges the viewers to not look away, demanding you keep up with its rhythm.

The film’s different sequences were inspired by meditation sessions which Man began two years ago. The scene in which Man’s young cousin watches a video of a cochlear implant surgery comes from a real memory of being traumatized by the process. “I remember having to grow up really quickly and make a decision that I knew would impact the rest of my life, even when I couldn’t understand its weight long-term,” he said. The sex scene which shows Man topping his partner, played by the queer healer and sex worker Sammy Kim, was another revelatory moment for the artist. “Showing my trans body in that position was empowering but also a reference to fucking myself—the whole film is about self-exploration and self love,” said Man.

Coming of age with a wire and magnet on his head, Man has related to the iconography of the cyborg for most of his life. “My head would get connected to the locker room walkways because of my wire,” he remembered. Having his start on social media through posts about his transition was instrumental in his journey while the digital realm’s role in his self-acceptance has also prompted him to see his journey similar to that of a cyborg’s: “This platform has allowed me to create my own representation and not wait for larger companies to uplift me—I could share the most intimate and vulnerable pieces of my life to others.”

The film’s sequences are bookended by confessional poetic text on the top and bottom of the screen. The writing above comes from Man’s reflections on his ear implants and him coming to the revelation of having the option to not wear it. Meanwhile, the words below echo the closed captions Man and those who are hard of hearing must rely on in order to live in a hearing-oriented society.

Crafting the film’s cast and crew was not different from any other of Man’s endeavors as someone who doesn’t separate work from his communities and families. “I am inextricable from anything that I ever create,” he said. “I identify as determined, curious, stubborn, and fast paced, as well as trans or disabled.” Man’s most recent projects, including The Device That Turned Me Into A Cyborg Was Born The Same Year As I Was, have been with his friends and families, both biological and chosen.

In addition to premiering in Sydney and London, the film had its New York premier last month at Leslie Lohman Museum to a large crowd that included family, friends, acquaintances, and fans. “Showing the film to my community at a museum that I’ve been visiting since I was 17 was a dream come true,” said Man, who was also recently appointed to the museum’s board. Following recent video art commissions from LGBTQ+ artists like Brontez Purnell and Young Joon Kwak, Leslie Lohman’s execute director Alyssa Nitchun believes the museum is the perfect platform for Man’s community bridging work. “The way Chella integrates all his different worlds so powerfully is very moving,” she said. “Now the museum is one of those worlds in which he can capaciously hold everyone.”

The near future is full of new chapters for Man. While the film travels the festival circuit, he will be working on black and white ink drawings on clay canvases for his solo exhibition at Hannah Traore Gallery in November. He considers this new body of work a full circle to high school when he only drew on white paper with black ink. “This binary between the two colors helped me think about discarding my own binaries,” Man explained.

This summer, his work will also be in a group exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York. Concurrently, Man is also launching a new artist residency program in Brooklyn’s Industry City. “You see, I like a fast pace,” he mused. “Growing up in a conservative place, I didn’t have many opportunities, so in a city like New York, I am always ready for the next thing.”

Osman Can Yerebakan is an art and culture writer and curator based in New York.