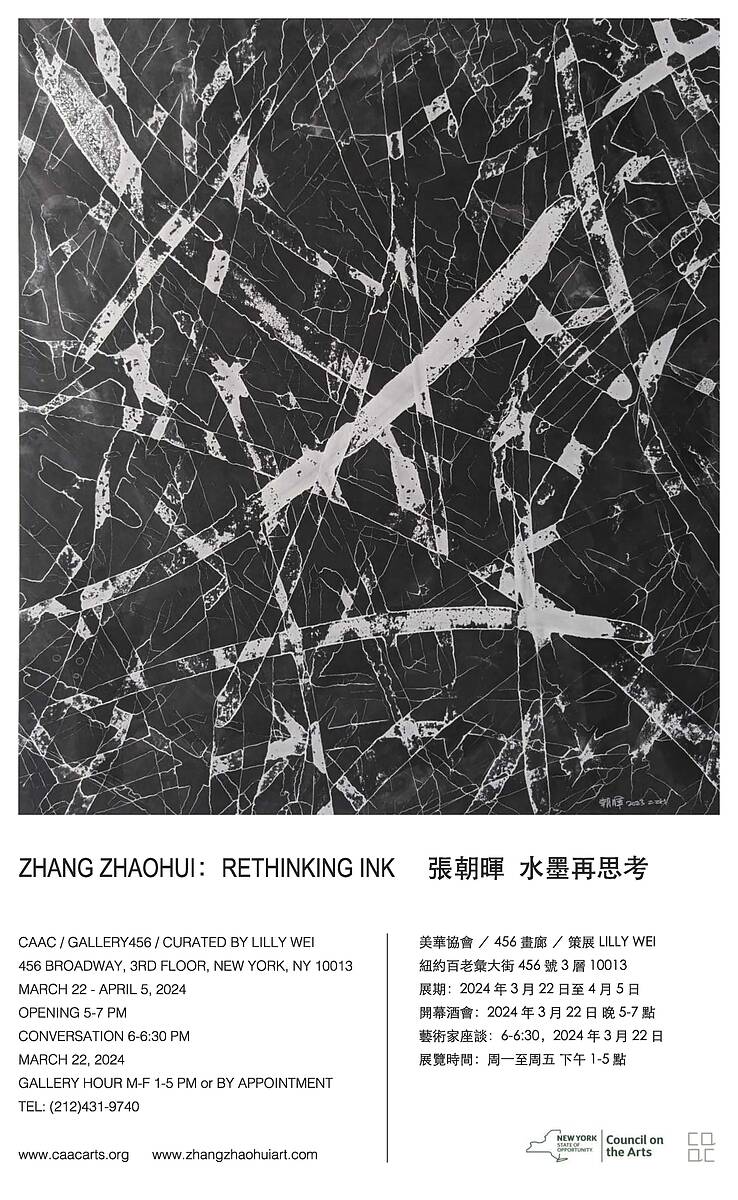

Zhang Zhaohui: Rethinking Ink

1 – 5PM

Artist Talk: Friday, March 22, 2024, 5:30pm–6:00pm

Opening Reception: Friday, March 22, 2024, 5:00-7:00pm

Chinese American Arts Council/Gallery 456 is pleased to present Zhang Zhaohui: Rethinking Ink, curated by Lilly Wei, on view from March 22, 2024 through April 5, 2024.

Zhang Zhaohui (b. 1965, Hebei Province, China) has long been drawn to modern and contemporary American art, particularly to Minimalism but also more expressive formulations such as Abstract Expressionism. At the same time, he is wholly enamored of Chinese ink wash painting and has been since he was ten, when he first encountered Qi Baishi’s (1864-1957) paintings, a self-taught artist who modernized classical Chinese Xieyi style painting. Zhang is not alone in his love of the medium, the demand for it prompting a parallel (and deeper) appreciation of contemporary ink wash projects. He is critical, however, of those who practice it without a firm grasp of its principles, which includes an understanding of how to adapt its techniques and thinking into the present, how to make it a living medium rather than merely imitating past creations. His own pictorial language is derived from an informed knowledge of the historical and more recent art of several cultures, most significantly European and American modernism (monochrome, Zero, Op art, for instance) but also Taoist and Buddhist thought, the Japanese mono-ha school, and Korean monochrome, in addition to ink wash traditions. Connecting past and present and threading together different cultural aesthetics, his aim is to refresh and enrich the old and make it new, make it his own, something artists have always done.

Zhang was educated in China and the United States. He studied at Nankai University and graduated with a degree in museum studies, but because of his interest in contemporary American art, he attended the curatorial program at Bard College in upstate New York and served as an intern at Asia Society in 1998, advocating (unsuccessfully) for the inclusion of ink wash painting in the eye-opening exhibition Inside/ Out that put Chinese contemporary art on the international map. Returning to China, he earned an MFA and PhD from the Chinese National Academy of Arts and the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, currently dividing his time between Beijing and New York, his bi-cultural credentials of long standing.

It is not surprising that Minimalism was one of the movements that attracted him, since its concepts are not dissimilar to Asian aesthetics and philosophies, the exchange of influences reciprocal. As with ink wash, Zhang uses Minimalist ideas as something to begin with in his constant search to discover new pictorial possibilities within parameters that he finds meaningful. That includes the balancing of opposites: “purity” and “restraint” with the palpable and sensual, with the phenomenal; objectivity with subjectivity; and an emphasis on materials as well as the more ineffable.

The 29 paintings in this exhibition are part of that ongoing investigation. They are from 2015 - 2023, the titles mostly descriptive, the measurements ranging from small to large, even extra-large. All are gray, the tonalities scaled light to dark, although Zhang does sometimes use color—for its expressiveness and greater unpredictability, its more irrational appeal—but not here. The earliest paintings, Linear Light (2015), Uncertainty (2015) and Uncertainty (2016) give us a basis of comparison between then and now, and how his work has changed in the interim. Linear Light consists of a weave of countless, slightly wavering intersecting lines drawn with a brush. It is a grid, but one that is on a diagonal, an orientation that he favors. The shadings are subtle, and at the work’s center, an area of luminous white is glimpsed that seems to advance and recede, a gently beating heart of light. Flickering pinpoints of white dotting the lines further animate the surface, Zhang’s deft brushwork transforming the grid’s austerity into something softer, more yielding, personal. Uncertainty (2015) is a combination of light and dark, the weave now backgrounded, intertwined with bleached forms that might suggest tree trunks, roots, contrasting the organic with the geometric, part of his ongoing juxtaposition of opposites. In Uncertainty (2016), the imagery is even more diaphanous, the edges tremulous. While the cross patterning of the support is once again evident, the position of the overlaid imagery is ambiguous, in play. Is it moving outward toward us or is it receding into the painting’s depths, is it coming into being or is it in dissolution, questions that reflect the fluidity of our existential state.

Brush Traces (2022) is a series of works that are just slightly larger than a legal-sized sheet of paper, but as arrestingly complex as the more imposing paintings. They possess the spontaneity of studies, but are executed with his usual meticulousness, a virtuoso exercise in variations to show us how infinite the resolutions can be even within Zhang’s self-imposed limitations of ink, brush, and paper. Carl Andre, the late, pioneering minimalist sculptor once said in a New York Times interview: “…it is limits that give us possibilities. Without limits nothing good can be accomplished. I feel I’ve been liberated by them.” I think Zhang would agree.

The disappearance of the slanted grid is a change here, but the diagonals remain, to keep things lively, and the figure/ground relationship is more defined in several of the works, although the ground asserts itself in others, sometimes appearing torn, collaged. The compositions alternate between the allover and the reductive, as fine lines streak across the surface like fingers of electricity or, in the emptier fields, configured like a macro- or micro-mapping of some imagined realm. It is of note that the outlines in Zhang’s output are often white, as if drawn with light, their edges impossibly delicate, exquisite, a reversal of the customary black used in ink painting. He also includes another system of edges by allowing different densities of ink to bleed into each other, that network more the result of chance.

What he gleaned from his intensive year with Brush Traces, he transferred to Entanglements, a series that he began earlier (one painting shown here is from 2021), the others all from 2023, his most recent ventures, and the most flamboyant. One standout is also the largest on view, an almost baroque construct of intricate, intersecting, diagonally placed rods, a more extravagant version of the translucent fragments that suggested shards of glass in the Brush Traces series. The slender crystalline rods are scattered across the field as if his former grid had been detonated, its stability in disarray, transformed into something that looks unsettlingly fragile, irrational. Yet, in another twist, what seems jumbled is not quite; when looked at closely, it is only a more complicated presentation of order.

Zhang made a special trip to New York to see Donald Judd’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 2020, discovering, to his surprise, that this master of the minimalist wasn’t a Minimalist after all (a label very few artists have embraced). And he is right. Many of Judd’s objects are not so severe, graced by unexpected poetry, especially the ones that include color. The light and color emanating from them and the reflections they cast are dazzling, transforming the deceptively simple, industrial boxes into things of undeniable beauty. Although their works are not visually the same, seeing the Judd’s from that perspective confirmed his own belief that the power in a work of art comes from an intuition shaped by the cumulative knowledge of the artist, and conveyed by his materials of choice in which beauty and sensations of pleasure is not ruled out.

Lilly Wei